World Sight Day: My life as a blind 'Luddite'

BBC

BBCThe majority of Wales' 107,000 visually impaired people do not have access to the internet at home, according to research for World Sight Day.

That is despite access to the internet at home being seen as key to reducing levels of social and financial inequality.

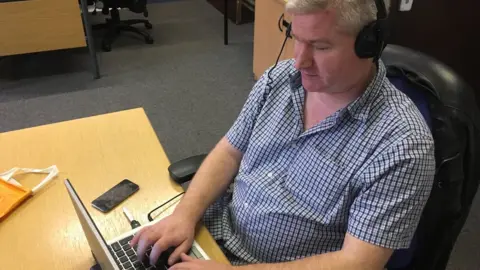

Neil Prior, a BBC journalist of 18 years, has been totally blind since the age of 13. He is a self-confessed Luddite.

I clearly remember the day I fell out of love with technology.

I'd been working as a researcher for BBC Radio Wales for around six months and had already made quite a reputation for myself as a demon editor of packages on quarter-inch tape.

Editing on tape was a highly tactile process; feeling the reel spool past the playing heads and your fingertips, nudging the speed control, and…bang! That's the point your razorblade needs to make the cut.

It was a thoroughly intuitive skill and one of the few things in life where a blind person is at a distinct advantage over sighted people.

Then came the day when our boss excitedly drew us into his office and revealed that quarter-inch tape was soon to be a thing of the past; we'd be editing on a computer package.

"No more razor-sliced fingers and shirts stained with chinagraph pencil", he enthused, "we'll edit in half the time at double the quality".

I was the only person to leave that office glum, as I knew that moment marked the point in my life from which I'd forever be playing catch-up.

Yet my pessimism is as much a product of my generation as it is one of my disability.

I wouldn't say I grew up before the computer age - despite appearances, I'm not quite that old - but my youth was one of Windows 95 and dial-up.

I know full well that blind people in their 20s are using smart phones for everything from controlling their heating to reading their post, but I'd rather chisel my meter-readings into granite with my bare teeth than have to contemplate submitting them online.

For those who jumped aboard the digital bus at the right time it has been nothing short of a revolution for blind people. For those of us who dithered finding our tickets, the relentless march of technology is a barrier not a gateway to social and professional inclusion.

Yet for once I feel unashamed to be a curmudgeon, as my feelings are for the first time borne out by bona fide academic research.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDr Yan Wu, who led the study on behalf of Swansea University's Colleges of Arts and Humanities and Science, told me that while digital lag can be a problem for all men of a certain age like me, the problems faced by blind people are more acute.

"Blind people do have more digital opportunities than ever before - the British standard code of practice ensures web products have to meet the requirements of the Equality Act 2010," Dr Wu told me.

"The problem is that if you're blind you have to be much more digitally literate to access them.

"People who can see don't have to try and be technically savvy, the technology is designed to be visually intuitive. It's not at all intuitive if you're using the same applications with speech software.

"Imagine coming to work, and before you can start your job, you have to know how to set up your computer from scratch; these are the sort of issues which are putting off blind users."

That last point rings painfully true for me.

I remember the first time I was handed a smart phone, and told: "Apparently it has speech software on it, so just play around and figure it out."

You might as well have handed me a copy of War and Peace in the original Russian, and told me to figure that out.

'Expensive'

Which leads on to Dr Wu's next finding: digital training for blind people is extremely difficult to find, far less afford.

"There is excellent training out there, from our partners in the RNIB in particular, but because they're dealing with such specialised software, and the training has to be delivered one-to-one, it can be very costly indeed, and waiting lists can be massive," he added.

"Software itself can cost over £800 to purchase, and when you consider that only 25% of blind people are in full-time employment, the boundaries to digital inclusion soon mount up."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAccording to Dr Wu the answer lies in moving away from adapting sighted applications to work for blind people, to making software and hardware which is accessible to everyone from the outset.

"We're already starting to see the way forward with voice-activated equipment and the way blind people use them is exactly the same as sighted, so there's no adaptation or training necessary.

"Apple and some Android phones are making devices with accessible software built in, and I think increasingly you'll find that expensive third-party applications will become a thing of the past."

So there you have it: 'Alexa, drag me into the 21st Century!'