Fossils from when Wales and Canada were joined together

BBC

BBCIn the basement stores of National Museum Wales in Cardiff, Caroline Buttler is giving a private tour.

As the head of palaeontology, she is in charge of the museum's 300,000 fossil specimens - many not usually seen by the public.

Among the drawers and shelves that stretch floor to ceiling - carefully set at the right temperature and humidity - are wonders of the natural world.

There are pieces of mammoth skin and teeth, fossil plants collected from working coal mines, ammonites that once swam in Jurassic seas and the oldest fossils in Wales, stretching back more than 560 million years.

Ancient sea snails are stacked with large ichthyosaur fossils, while one star attraction - a 190 million year old fossil of a sea dragon with an eye bigger than a dinner plate - is on a trolley, having recently starred in a David Attenborough documentary.

For Dr Buttler, whose job it is to oversee the preservation of these hidden artefacts, working with such diverse specimens is a "real privilege".

She said: "Many of our prize exhibits are on display in the museum for people to see in our galleries.

"The Welsh dinosaur is really popular and we have 3D reconstruction of what it would have looked like when it was alive.

"But we have hundreds of thousands more specimens in the stores, which show how life on earth has evolved through millions of years of geological time.

"People come from all over the world to do research on them.

"One scientist came from Switzerland for four days during the recent snow, but ended up getting stuck here for two weeks. He was in heaven."

For Dr Buttler herself, paleontology has been a long-standing passion.

"I remember seeing my first ever fossil on TV when I was four," she said.

"It was on Playschool and it showed the famous Diplodocus at London's Natural History Museum - which is coming to visit us in Cardiff next year.

"My parents took me to see it and I was astonished by the size."

This love affair with fossils saw Dr Buttler go onto study geology at sixth form and at Liverpool University.

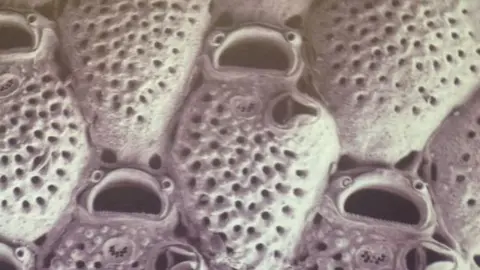

After spending time in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, studying fossilised corals, she then completed a PhD at Swansea University on fossil bryozoans - tiny aquatic invertebrates - then postdoctoral research in Dublin, before joining the museum in 1990.

Initially in charge of the conservation of geological specimens, she then moved up the ranks to become the head of palaeontology - the first woman to hold the position.

She also continues to carry out research into bryozoans from Wales, comparing these 450 million year old animals to others throughout the world, and having two species named after her.

Dr Buttler said: "When people think of palaeontology, they think of dinosaurs, but there's so much more than that.

"Most animals that get preserved as fossils lived in the sea, and usually we just find the hard parts such as shells and skeletons.

"But sometimes we get the soft tissue preserved and it's very exciting.

"We have a trilobite from North America in the collection with beautifully preserved legs and antennae, which really brings the creature to life."

Much of the work she and her team do involves looking at individual fossils to garner clues about what the environment was like when they lived.

She said: "We look at which animals were living together, how they interacted and build up a picture of what their world was like millions of years ago.

"We know, for instance, that Wales was joined to southern Newfoundland in Canada 510 million years ago, as the fossils found in both regions are exactly the same.

"Scientists can also look to the future and predict how the world will change.

"In one possible scenario, over 250 million years from now, America will be joined to Africa, Australia will be linked to Antarctica and Britain will be near the North Pole."

Such is Dr Buttler's love of her job, even during her holidays and downtime she can sometimes be found fossil collecting.

She said: "Wales has an amazingly diverse geology and is a great place to collect fossils.

"Even after many years in the job, I still love working with and finding fantastic specimens.

"They give me such a massive sense of wonder."