Has Wales' economy lacked the big idea?

XtockImages/Getty Images

XtockImages/Getty ImagesWe have passed the milestone marking two decades of devolution in Wales. But do we feel better off?

In economic terms it seems not.

Compared with the UK, Wales has fallen behind in terms of productivity, household income and earnings.

Welsh productivity in terms of gross value added (GVA) per hour worked was 86.8% of the UK average in 1997, and much lower in 2015, at 80.6%.

When you look at GVA per head it has fallen steadily.

The common defence is that it is not because Wales is failing but rather it is that London and the south east is growing at such a fast rate that it distorts the average.

In the past, I have been taken in by that view but comparing Wales with Scotland that argument begins to falter. In 1997, Scottish GVA per hour was 94.8% of the UK average and in 2015 was 98.3%.

So why has Wales fallen behind?

By 1997 most of the structural change of the Welsh economy - the decline in coal and steel - had already taken place. Wales had enjoyed years of high levels of inward investment, particularly from Japanese manufacturers of consumer products, like TVs and microwaves, producing here to sell into the new European single market.

It is hard to argue that the decline of traditional industries was the main reason that Wales fell behind in the last 20 years, although many communities were still ravaged by the effects of that.

That was recognised by the European Union as it awarded Wales the highest level of economic aid, Objective One, in 2000, 2007 and for a third period again in 2014.

Since 2000 an extra £5.3bn has been injected into the Welsh economy from the EU beyond other sources of income like the block grant from Westminster.

The way in which the first tranche of EU aid was spent has been criticised by a number of academics and the Wales Audit Office for lacking economic and geographical focus.

For example every local authority seemed to be awarded its own new arts centre, among other things.

But bearing in mind the closeness of the vote in support of devolution perhaps that was the right approach politically, even if it was not the best option economically.

The new money from Brussels was also used to try to get more people into work through various training programmes and childcare schemes.

Evidence suggests that nations and regions that choose a precise target for economic regeneration often succeed.

Ireland decided to go hook, line and sinker to attract technology firms, while the Basque country in Spain embraced radical urban planning and decided to stick with its traditional industries but modernise them through research and development.

So what has been the "Big Idea" for Wales in the last 20 years?

Wales scrapped government agencies in the so called "Bonfire of the Quangos" and gave voters free prescriptions and bus passes for older passengers. But those things do not in themselves make an economy vibrant.

The second and third tranches of EU regional aid have been characterised as working more closely with the private sector, but again without a single focus for the economy. Instead they have instead a broad approach to increasing jobs and productivity.

There have been nine priority sectors for the economy.

It was difficult to identify an industry which did not fit into one of those.

But now Economy Secretary Ken Skates has announced that this number would be reduced to three as part of his new economic strategy.

There have also been industry-specific techniums to help business growth. Directing the private sector to work on certain sites does not seem to have been popular, with a few exceptions such as the Optic Centre at St Asaph.

What certainly has been a major achievement for Wales, and which might not have been expected, is the halving of Welsh unemployment rates reducing it to the same as the UK average.

In 1997 unemployment in Wales was 7.2% while the UK was 6.6% . Now both are 4.3% That is no mean feat and something similar economic areas like the north east of England have not managed.

But at what cost? Low wages?

Comparing Wales and Scotland, in 1997 middle earners in both countries were paid £301 a week. In Wales, that now stands at £492 a week whereas in Scotland it is £42 a week higher at £534.

Similarly, household incomes, which include benefits, pensions and investments, as a proportion of the UK average have risen in Scotland and fallen significantly in Wales.

With Scotland's oil and gas industries declining it is perhaps surprising that Scottish economy has performed so much better than Wales since devolution.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhat we do know is that the Scottish government has given considerable support to renewable energy and in particular onshore wind.

Another contrast with Wales is that Scotland has retained its regional development agency Scottish Enterprise, whereas the Welsh Development Agency was scrapped in that quango cull.

But surely the answer to Scotland's success must lie in more than that?

So why hasn't Wales performed better? Critics of Welsh economic policies often argue that there has not been a single, finely-targeted, big idea and that economic policy has not changed significantly since the 1990s.

Other approaches have been suggested by Welsh academics like Prof Calvin Jones, Dr Mark Lang and Prof Karel Williams and others.

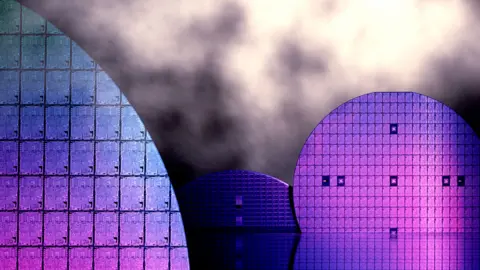

CraigDyball/Getty Images

CraigDyball/Getty ImagesIt is worth noting that one of the most exciting economic developments in recent years is the compound semiconductor Catapault cluster and foundry in south east Wales.

It has been driven by the private sector, the Welsh firm IQE, and attracted significant investment and support from others in the private sector, Cardiff University, the Cardiff Capital Region as well as Welsh and UK governments.

That really does have the potential to change the economic landscape of Wales.

Any analysis of the Welsh economy since devolution needs to remember that without it, Wales would have had to deal with the full thrust of austerity.

The Welsh Government protected public services to some extent, and local authorities in Wales did not have to face budget cuts to the same extent as English ones.

Similarly the Welsh React and Proact programmes helped protect jobs and companies in Wales the as effect of the financial crisis of 2008 hit. Without those, and programmes like Jobs Growth Wales, the Welsh economy might well be in a poorer position now .

We must not ignore the fact that devolution gave tools to the Welsh Government to steer the economy to a certain extent but the big economic levers - setting income tax, interest rates and benefit levels - stayed with Westminster.

The challenge for Wales now is to learn from the past 20 years, use the tools it has, and be bold about the future.