Declaration of Arbroath: Scotland's most famous letter goes on display

One of the most famous documents in Scottish history has gone on display for the first time in 18 years.

The Declaration of Arbroath was written on 6 April 1320 by Scottish nobles asking the Pope to acknowledge Scottish independence.

The fragile text can only occasionally be shown in public to ensure its condition is preserved.

It will be on display at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh until 2 July.

The letter was one of three written to Pope John XXII, who refused to recognise King Robert I - Robert the Bruce - as the monarch in Scotland.

The King and the Bishop of St Andrews also wrote to the Pope, but the barons' letter is the only surviving document.

Their collective plea was unsuccessful as the Pope's reply urged reconciliation with the English.

The two countries had been fighting against each other in the Wars of Scottish Independence since the English invasion of Scotland in 1296, with Robert the Bruce leading the Scottish army to a famous victory in the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314.

The first war of independence eventually ended with a peace treaty in 1328, but a second war erupted four years later and continued for 25 years.

Dr Alan Borthwick, head of medieval and early modern records at the National Records of Scotland (NRS) said the declaration helps people understand the political feeling at the time.

He said: "It encapsulates an awful lot about what the Scots thought about themselves as a nation in 1320 and their rights to be an independent kingdom, not subject to the English king.

"The way that it is written, using quotes from the Bible but also classical authors - it's a very, very carefully crafted text.

"It is strongly asserting their position as supporters of Robert the First as their king without having to get an approval from the king of England."

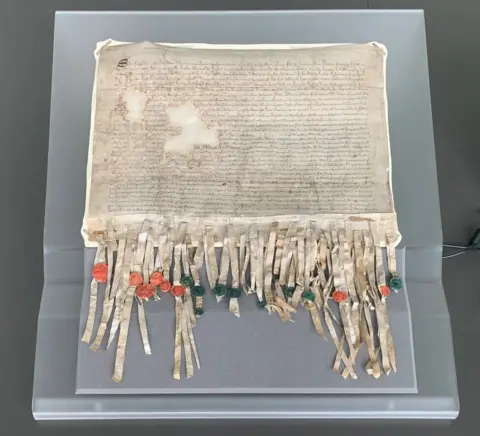

The Declaration was written in Latin and was sealed by eight earls and about 40 barons.

One of the most famous quotes of the roughly 1,000-word long text still inspires the Scottish independence movement 700 years later.

PA Media

PA MediaIt reads: "As long as a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be subjected to the lordship of the English.

"It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself."

Dr Borthwick said: "There are a number ways in which you can interpret the text.

"There is the context in which it was produced, and for some undoubtedly it is the context that it may have in more modern times.

"It's phrases like that which undoubtedly resonate across the generations and across the centuries and across the world. When you think of people fighting for freedom, that is really what it's about."

Some historians claim its significance has been overstated and the purpose of the declaration was simply to shore up the reign of the Scottish king.

The Declaration of Arbroath display has been organised in partnership between National Museums Scotland and NRS, who keep the document.

The letter is usually kept in a temperature-controlled secure location with limited access and no light.

It is vulnerable to degradation as it is made from sheep skin, and moving the document for display is a very complex process.

Linda Ramsay, who heads up conservation at the NRS, has worked on preserving the Declaration of Arbroath since 1991.

"It is a great privilege to be so close to these real history-making documents," she said.

"It's a totemic document, certainly for a Scot. It has a lot of challenges but it is a real privilege.

"With display there are so many vulnerabilities and so many factors that we are not in total control of."

She said she feels nervous when the document leaves the managed space, adding: "We like it to be back sleeping in its bed in the store secure.

"We're pleased that people are going to see the Declaration. A public record is something you can't just keep and nobody sees it, there is an interest and quite rightly we have to make that possible."

Analysis by Lorna Gordon, Scotland correspondent

We were given rare access to film the Declaration of Arbroath ahead of it going on display.

In a room where both the temperature and humidity were tightly controlled, we watched as expert conservators from the NRS inspected the document, looking for and recording any signs of deterioration in its condition.

They explained to me that a visual examination is carried out any time a significant document goes on display.

The 700-year-old letter is normally kept in a case in a darkened room. We weren't allowed to use artificial lights with our camera when we filmed and instead relied on daylight from the huge windows in the north-facing room to illuminate the medieval writing and seals.

There was also UV laminate on the window panes to reduce any potential damage from sun light.

The cupboards in the lab-like room held vellum and dyes and more exotic sounding material such as Goldbeater's skin. Linda Ramsay, head of conservation at the NRS, said their aim was to slow down degradation and preserve the Declaration of Arbroath in the best state they can for future generations.

We took an immense amount of care while filming and moving around the 14 Century priceless, fragile document. Being allowed such close access was both a privilege and a responsibility.