Why is there a row over seaweed harvesting in Scotland?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA review of regulations around the harvesting of kelp from waters around Scotland is to be launched by the Scottish government, amid a row over whether large-scale commercial operations should be allowed. What's going on, and what does it all mean?

What's this all about?

It's about seaweed. Or a particular type of seaweed. Kelp, to be precise.

If there's one thing Scotland isn't short of, it's coastline. And off the coast lie fertile grounds for the production of seaweed, with vast forests of kelp off the Western Isles and Orkney in particular.

Kelp plants don't have roots; instead they anchor themselves to rocks on the seafloor before growing rapidly up towards the surface. Some species of giant kelp can grow by as much as 30 to 60cm vertically per day.

Traditionally it has been harvested on the shoreline, by hand. Seaweed has been used in the production of things like soap and glass, and is also gathered by crofters for use as fertiliser.

But commercial firms are now turning their eye on the dense forests of kelp that grow off the coast, where much greater quantities can be harvested directly.

This already goes on in countries like Norway and Chile, where up to 200,000 tonnes of seaweed can be collected in a year.

Why would anyone need that much seaweed?

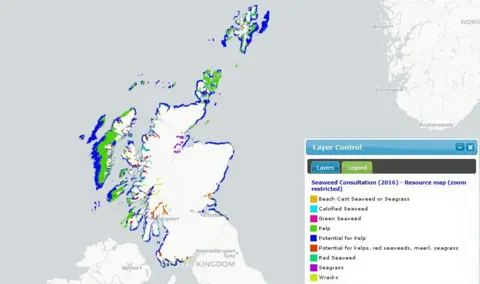

Marine Scotland

Marine ScotlandIt's not just useful for soap and manure. The number of potential commercial applications for kelp, particularly the nanocellulose which can be produced from it, is growing all the time.

One Scottish company, Marine Biopolymers Ltd (MBL), has applied to harvest up to 30,000 tonnes of a specific species of kelp - Laminaria hyperborea - off the west coast each year.

This is a very abundant species of kelp - there are an estimated 19.7m tonnes of it off Scotland's coasts, meaning the firm would be targeting about 0.15% of it.

The firm would collect the kelp using Norwegian-style harvesting vessels, which would bring their haul back to a harvesting plant in Mallaig.

MBL are working on a number of potential products derived from the seaweed, ranging from a "transparent armour" for police and the armed services to slow-release drugs for treating colon cancer and medical implants and meshes.

The firm claims that the kelp-harvesting industry is perfectly sustainable, and could be worth up to £300m a year.

What could the downside be?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOpponents of mechanical harvesting include green groups and politicians, who say the practice can have an adverse impact on sealife and even on land.

There are concerns that industrial-scale harvesting can strip whole plants off the seabed, making it hard for them to grow back.

A range of plants and animals call the kelp forests home - everything from sea anemones to sponges, pollack, wrasse and saith. Cutting them back can destroy the habitat of young fish and invertebrates and feeding grounds for seabirds.

There could also be an impact on the shoreline, as a thick bed of kelp can absorb energy from waves, dampening their strength before they reach land - so there are fears removing it could cause coastal erosion or even flooding.

A petition circulated by a Green MSP gathered 14,000 signatures opposing what they call kelp dredging (a term that MBL contest, saying "you can't dredge a rocky bottom").

Veteran naturalist Sir David Attenborough has also spoken out, saying it is "absolutely imperative that we protect our kelp forests".

Despite all this, a strategic environmental assessment by Marine Scotland in 2016 concluded that "although not straightforward, sustainable commercial scale harvesting of certain species is possible".

So what's being done?

As things stand, commercial harvesting of kelp from the sea bed requires a marine licence. The Scottish government says the licensing regime "sets a presumption in favour of development that is sustainable".

However there is now going to be a review of the regulations around harvesting, as announced by Environment Secretary Roseanna Cunningham on Wednesday.

She defended the current licensing system, calling it "robust", but said "continuous improvement" was needed where there were "new or novel activities".

This came after Green MSPs claimed that Marine Scotland was too close to MBL, having obtained letters apparently showing the regulator praising the firm's "innovative proposal".

Ms Cunningham said members should welcome the Scottish government and its agencies "looking at innovative industries and thinking about new technologies and what might be developed in Scotland in the future".

Meanwhile, opposition MSPs have sought to bring in measures to restrict mechanical harvesting, successfully amending the Scottish Crown Estate Bill to bar techniques which "would inhibit the regrowth of the individual plant".

However this only applies to Crown Estate land, which covers about half of the foreshore, and includes various provisions to allow research and development and maintenance work at power stations and ports.

Ms Cunningham said she would write to MBL, and urged other companies which want to be "part of this burgeoning industry" to "continue to engage with the government and relevant authorities".