Scotland and fracking: How did we get here?

The Scottish government has confirmed that it wants to effectively ban fracking in Scotland.

Energy Minister Paul Wheelhouse told the Scottish Parliament that the current moratorium on fracking will be continued indefinitely - which he said means that fracking "cannot and will not take place in Scotland".

Here's a look at the background to the announcement.

What is fracking?

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is a technique used to recover gas and oil from shale rock by drilling down into the earth before directing a high-pressure water mixture at the rock to release the gas inside.

Water, sand and chemicals are injected into the rock at high pressure which allows the gas to flow out to the head of the well, where it can be collected.

Fracking allows drilling firms to access difficult-to-reach resources of oil and gas, and has been credited with significantly boosting US oil production.

But opponents point to environmental concerns raised by the extensive use of fracking in the US.

They say potentially carcinogenic chemicals used in the process may escape and contaminate drinking water supplies around the fracking site, although the industry argues any pollution incidents are the results of bad practice, rather than an inherently risky technique.

There have also been concerns that the fracking process can cause small earth tremors.

And campaigners say the transportation of the huge amounts of water needed for fracking comes at a significant environmental cost.

How much shale gas is there in Scotland?

PA

PAAccording to a British Geological Survey report published in 2014, there are "modest" shale reserves under east Glasgow, North Lanarkshire, South Lanarkshire, West Lothian, Midlothian, north Edinburgh, East Lothian and Fife - many of which include some of Scotland's largest towns.

There was estimated to be about 80 trillion cubic feet of shale gas in central Scotland compared to 1,300 trillion cubic feet in the north of England.

The report also said the amount of oil and gas which could be commercially recovered was likely to be substantially lower.

Ineos, which operates the huge Grangemouth petrochemical plant in central Scotland, holds fracking exploration licences across 700 square miles of the country.

The company has also started shipping shale gas ethane to Grangemouth from the US.

Its chairman, Jim Ratcliffe, has previously claimed a domestic shale gas industry could secure Scotland's energy supply in the future and revitalise the country's industrial heartlands, with Grangemouth becoming a "new Aberdeen".

But Prof John Underhill, an expert at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh, published research in August which he said showed that the geology of the British Isles made large scale hydraulic fracking unviable.

What had the Scottish government's position been until now?

PA

PAUnder pressure from environmental campaigners, community groups and many grassroots members of its own party, the SNP government at Holyrood announced a moratorium on fracking and a separate process called underground coal gasification (UCG) in 2015.

The moratorium led to UCG - a method of extracting gas from coal seams that are too deep underground for traditional mining techniques - effectively being banned last year after "numerous and serious environmental risks" were identified.

Separate reports into the environmental, health and economic impact of fracking were published a few weeks later, before a full public consultation was held on the issue.

The reports found "inadequate" evidence to draw a firm conclusion on the health impact of fracking, while the probability of "felt earthquakes" was rated as "very small".

The economic report laid out a series of different scenarios, with anything from 470 to 3,100 jobs potentially created, and value added to the Scottish economy to 2062 anywhere from £100m to £4.6bn.

Holyrood had previously voted to support an outright ban on fracking, although SNP members abstained from the non-binding vote - with Labour also launching a members bill which had the same aim.

The Scottish government has officially remained neutral in the fracking debate while it weighed up the evidence for and against.

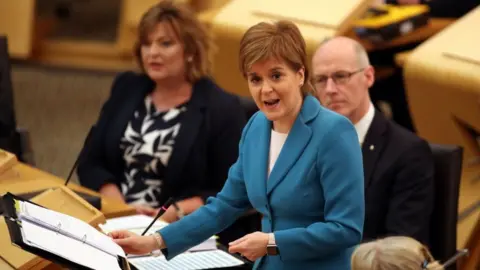

But First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said in March of last year that she was personally "very sceptical" about fracking and had some "big questions" about the impact it could have on health, the environment and local communities.

What happens next?

The Scottish government has now confirmed that it will not support the extraction of any unconventional oil and gas in Scotland - meaning that fracking has effectively been banned.

Mr Wheelhouse told Holyrood that 99% of people who responded to the Scottish government's consultation backed the move.

It means that the SNP, Labour, Liberal Democrats and Greens are all now officially in favour of a ban, with only the Conservatives opposed - making the final vote on the issue, which is expected to happen after the October recess, something of a formality.

The announcement is likely to be given a warm welcome by party activists gathering at the SNP conference, which opens on Sunday.

But there have already been reports that Ineos could consider legal action against the government to recoup the £50m its says it has invested during the fracking moratorium.