Star quality: What does it take to win the Michelin award?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor decades, restaurants have been vying to earn one of fine dining's most coveted awards - a Michelin star. But what does it take to win one?

On Monday some of Britain and Ireland's most talented chefs gathered for a sizzling ceremony in London.

They were there to collect one or more stars from the Michelin Guide, regarded by many as the "bible" of fine dining since the awards were first given out nearly a century ago.

It was a triumphant occasion for the nine-seat London sushi restaurant The Araki, which joined a very short list of British three-star winners.

Other successes included a first star for the Loch Bay restaurant, based at a converted crofter's house on the Isle of Skye. But there was also pain for the Scottish island as Kinloch Lodge lost its star status.

Many of the new recipients described their "passion" for food and the importance they attached to winning a star as they collected their awards.

But how does an aspiring chief or restaurant go about achieving star status?

The answer is: they don't - at least not directly.

For decades, guide inspectors have been visiting establishments anonymously to assess their suitability for an award. They also pay for their own meals, in order - the guide says - to "maintain the independence of their opinion".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMichelin keeps much of its approach under wraps, but does outline five main criteria for inclusion in the guide - quality of the products; mastery of flavour and cooking techniques; the personality of the chef in his cuisine; value for money; and consistency between visits.

Depending on the assessment, inspectors can award one star ("very good cooking in its category"), two stars ("excellent cooking, worth a detour") or three stars ("exceptional cuisine, worthy of a special journey").

Since 1997, they have also awarded "bib gourmands" for eateries which offer "good quality, good value cooking".

According to Michelin, any restaurant can be recommended by its guide "as long as its food is of high quality".

It adds: "Restaurant inspectors do not look at interior decor, table setting or service quality in awarding stars - these are instead indicated by the number of 'covers' it receives, represented by the fork and spoon symbol."

Michelin

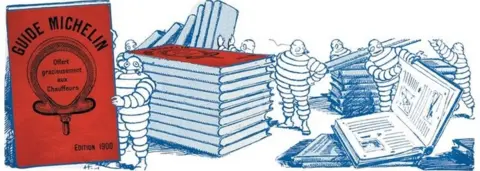

MichelinHistory of the Michelin Guide:

1889: Brothers Andre and Edouard Michelin found the Michelin tyre company in France

1900: First edition of the Michelin Guide is published. Covering France, it lists things that would be useful for motorists such as such as maps, information on how to change a tyre, where to fill up on petrol and where to eat or take shelter for the night.

1926: The guide begins to award stars for fine dining establishments, initially marking them only with a single star

1931: A hierarchy of zero, one, two and three stars is introduced

1936: The criteria for the starred rankings are published

2006: Michelin expands outside Europe with the launch of its New York guide, later expanding to some other major US cities, and to parts of Asia.

2018: GB and Ireland Guide includes five restaurants with three stars, 20 restaurants with two stars and 150 establishments with one star

Source: Michelin

While the guide is widely respected across the hospitality industry, some restaurateurs have spoken of the pressure a top rating can bring.

Last week, a Scottish country house hotel said it was "extremely proud" of its Michelin star but wanted to drop it because the dining guide's expectations were "at odds with achievable profit margins".

Wendy Matheson, who runs Boath House in Moray with her husband Don, said those expectations also put "an enormous stress on a small family-run business like ours".

Her comments came a week after celebrated French chef Sebastien Bras, whose restaurant boasts three Michelin stars, asked to be stripped of the honour because it put him under "huge pressure".

He told reporters that the endorsement had brought him "a lot of satisfaction," but he dreaded knowing Michelin testers could appear at any time.

Others in the business argue that the rating should be kept in perspective.

Leading British hotelier Ken McCulloch, who founded the hotel chains Malmaison and Dakota, held a Michelin star when he ran One Devonshire Gardens in Glasgow.

However, he says he is not chasing the accolade for his new Dakota Deluxe hotel in Glasgow.

He explains: "There is no doubt that receiving a Michelin star is the pinnacle of a number of restaurateurs' careers.

"When we received our award at One Devonshire Gardens it was delightful - it raised the bar.

"In my world I strive to make my hotels and restaurants a little bit better every day. That is my focus. A Michelin star can only help that but it should not be taken literally. It should be kept in perspective."

Food writer and restaurant critic Andy Hayler, who says he is the only person to have eaten in every one of the world's 100-plus three-star Michelin restaurants, agrees that eateries should focus on the food rather than the surroundings if they want to collect a much-coveted star.

He says: "Michelin awards stars these days to pubs, sushi bars and even the odd hawker stall in Asia, so it is clear that there is no requirement for the trappings of fine dining to earn a star, which is all about the food.

"Restaurants operate on tight margins, and fine dining brings many costs with it: lots of highly trained chefs, expensive glassware, the laundry of all those white linen tablecloths.

"However, this is a choice that the restaurateurs make: Michelin is not holding a gun to their heads demanding a certain style of dining.

"The Sportsman in Kent gets a well-deserved star despite being in a rickety pub, and tiny Sushi Saito in Tokyo earned three stars when it was still in essentially a large closet inside a municipal car park - no expensive tablecloths and glassware there."

He adds: "If a restaurant wants to change direction and go for a more casual style then so be it.

"The Michelin Guide is intended to help diners choose where to eat. It is not, whatever some may think, for the benefit of chefs."