Why is there a row over Scotland's longest road?

BBC

BBCPeople are being asked for their views about the project to upgrade Scotland's longest road.

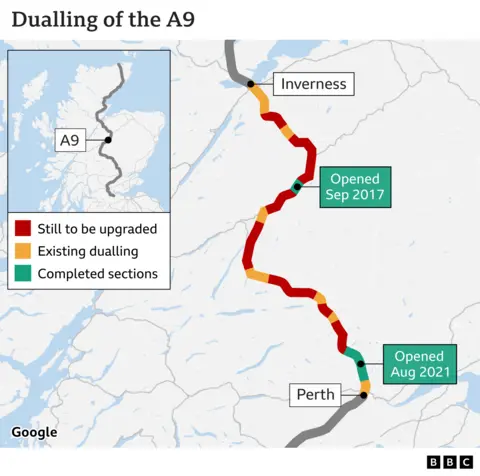

The work to dual the remaining single-carriageway sections of the A9 between Inverness and Perth was meant to be finished by 2025.

But since 2011, about 11 miles of the road have been completed - leaving 80 miles still to be done.

Holyrood's public petitions committee has launched a consultation to gather views on how the work could potentially be carried out more quickly, such as dualling several sections at the same time. The consultation is linked to a petition raised by A9 safety campaigner Laura Hansler.

The A9 is often described as the spine of the Scottish road network.

The trunk road runs about 230 miles from Scrabster, near Thurso on the north Highland coast, to near Dunblane in central Scotland. The A9 then continues to near Falkirk.

It passes through some dramatic landscapes, with some sections following the lines of old military roads dating back to the 18th Century.

Its highest points are 1,516ft (462m) above sea level at the Drumochter summit and 1,315ft at the Slochd summit.

The first major revamps of the A9, in the 1970s and 1980s, included bypasses of more than a dozen towns and villages - but most of the road has remained single carriageway.

The journey time to travel the whole length of the A9 - without any breaks or delays - is about five hours.

Why do people dread driving it?

Few people who make regular trips on the A9 would admit to looking forward to their journeys, and many will be familiar with the words "take care on that road" from friends and family.

Journeys are frequently long, raising the risk of fatigue, and it is busy.

Transport Scotland figures say more than 65,000 people travel along the Inverness to Perth section every day, and traffic levels can be 50% higher in summer due to tourism and leisure-related journeys.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAn estimated £19bn of goods are carried on the stretch each year and at times goods vehicles, including large articulated lorries, can account for up to 40% of daily traffic.

In winter, snow and ice can make driving conditions difficult.

Safety campaigners have blamed the mix of single and dual carriageway for causing confusion and leading to accidents - and there are concerns around driver behaviour.

The A9 Safety Group said more than 40% of fatal accidents on single carriageway sections of the A9 between 2008 and 2012 involved overtaking manoeuvres. It said excessive speeding was also a problem.

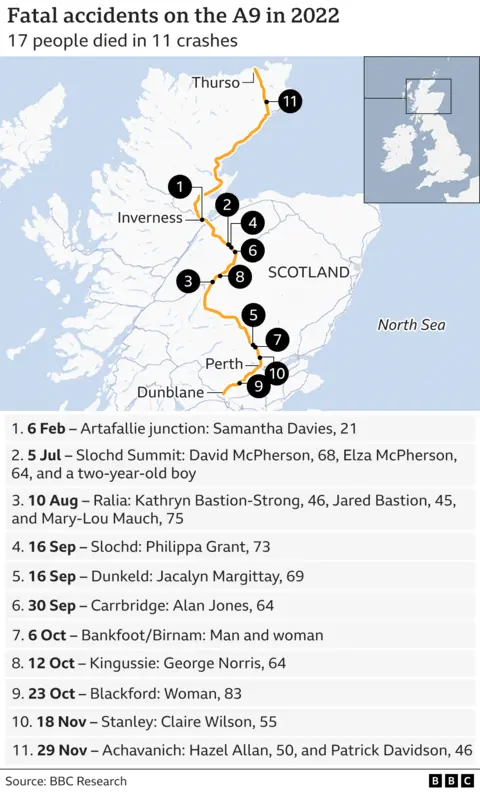

Last year the number of people killed in crashes between Inverness and Perth rose to its highest level in 20 years.

There were 13 fatalities, including a two-year-old boy and his grandparents who died after a crash at the Slochd, south of Inverness, in July last year.

The following month, three members of a family visiting Scotland from the US were killed at Ralia, also in the Highlands.

Along the full length of the A9 there were a total of 17 fatalities - the highest number for the entire road since 2009.

This sparked renewed calls from campaigners and politicians for the Scottish government to reaffirm its commitment to complete the dualling project by 2025.

What is the history of the project?

Transport Scotland

Transport ScotlandThere have been calls for the Inverness to Perth stretch to be dualled for many years due to its strategic importance, connecting the Highland capital with central Scotland, and because of the number of accidents.

In 2008, the Scottish government said improving the road was a priority.

In December 2011, it committed to dualling the A9 between Inverness and Perth by 2025 - a timescale which was described as "challenging but achievable".

Construction on the first section - the £35m, 4.6 mile Kincraig to Dalraddy stretch - started in 2015 and was completed in 2017.

The only other section to be finished to date was the Luncarty to Pass of Birnam project, which cost £96m and involved six miles of dual carriageway. Construction started in 2019 and it opened to traffic in 2021.

Nine sections remain to be built.

There are no plans to dual the A9 north of Inverness, where there are 104 miles of single carriageway from the Black Isle to Scrabster.

Why will the 2025 target be missed?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Scottish government has described the A9 as one of the biggest infrastructure projects in Scottish history.

Before the excavators can move in there is a huge amount of planning, public consultation, in some cases negotiations on the purchase of land and statutory process to be worked through.

Some of the terrain poses civil engineering challenges. The section at the Slochd involves an area of rocky hills and deep gullies.

The government has also faced opposition to parts of the project, including a section at the site of the 1689 Battle of Killiecrankie.

In February this year, then Transport Minister Jenny Gilruth told MSPs that meeting the 2025 target was "unachievable" - although the commitment to finishing the project was "absolute".

She said the project had been hit by delays and highlighted inflationary pressures on the construction industry caused by the impact of the Covid pandemic, Brexit and the war in Ukraine.

The cost of the project had risen since the original estimate of £3bn was calculated in 2008. The new figure has yet to be confirmed.

A major sticking point for progress is the six-mile section between Tomatin and Moy.

There was just one bid to carry out the work on this stretch, and at a price significantly higher than expected. The contract will now be put back out to tender.

How have people reacted?

Following Ms Gilruth's announcement in February, there was anger and frustration from the public, business leaders and politicians.

The Conservatives warned that people would continue to die until the road was made safer, while Labour said missing the target was a "total betrayal to the Highlands".

SNP MSP Fergus Ewing told BBC Radio Scotland's Drivetime programme he was "appalled" and called for a public inquiry into the delay.

"I am pretty angry about all of this, mirroring the anger felt by hundreds of thousands of people in Scotland," he said.

Highland-based safety campaigner Laura Hansler, who lives near the A9, said she had been close to tears.

"I feel physically sick because my thoughts are closely with those who have lost loved ones on the A9," she said.

Jo De Silva, chairwoman of Visit Inverness Loch Ness, said there could be an economic impact due to the importance of the road to an area which relies heavily on tourism.

However, SNP MP Drew Hendry called for understanding of the reasons for the delay.

"I don't believe anyone thought that the A9 dualling could have been completed by 2025 against the background of a Brexit, imposed upon us, and the pandemic," he said.

The Scottish government has asked Transport Scotland to urgently consider a range of ways to efficiently dual the remaining sections, and further updates are expected this autumn.

What is being done to improve safety?

A network of average speed cameras was introduced in October 2014 in an effort to reduce casualty numbers while work continued on the dualling programme.

The number of fatalities dropped, before rising again last year.

In December last year, the Scottish government said it would spend about £5m in extra road safety measures by 2025.

There will be enhanced signs and road markings at key locations between Inverness and Perth, including work to highlight where the road changes between single and dual carriageways.

The A9 Safety Group has also run campaigns on overtaking.

A driver fatigue campaign was launched this year, and a "drive on the left" initiative for foreign drivers was held over Easter.