The Highland peatbog seeking worldwide recognition

Steven Andrews

Steven AndrewsA vast area of peatbog in Scotland's Flow Country could become one of Unesco's newest World Heritage sites. But why do some people believe the landscape deserves the attention?

Heather Jardine was a girl when the machinery arrived to carve up the ground on hills around her home in Sutherland in the 1970s.

She remembers the peatbogs being drained as huge diggers were used to create massive ditches.

The land was being prepared for large blocks of commercial forestry, which involved the planting of millions of non-native trees.

Heather says: "It seemed quite exciting as a young child seeing all the planters and the activity.

"But later it was realised this had been the wrong thing to do.

"In the 2000s work started on taking all the forestry down and blocking up the ditches."

In the intervening years, the importance of the environment which had been damaged had become clear. The repair work continues to this day.

Norrie Russell

Norrie RussellThe Flow Country contains the most intact and extensive blanket bog system in the world.

This expanse of peatlands, bogs, pools, lochs, hills and mountains covers large parts Caithness and Sutherland in the north Highlands.

It is about 50 miles across - roughly the distance from Glasgow to Edinburgh - and covers almost a million acres of land.

The peatlands, which have been growing for 10,000 years, are formed by layers of waterlogged mosses and other vegetation as they die off.

The plant life does not fully decay due to acidic conditions, so the material retains some of the carbon it absorbed when at the surface of the bog.

In places, the peat is 10m thick - deep enough to submerge two double decker buses stacked on top of one another.

The Flows provide habitat for birds, otters and water voles, and is carpeted with sphagnum moss. Its other plant life include sundews, which feed on insects that get trapped in their sticky tentacles.

It helps combat climate change by storing an estimated 400 million tonnes of carbon. Damaging the peat risks releasing harmful greenhouses gases into the atmosphere.

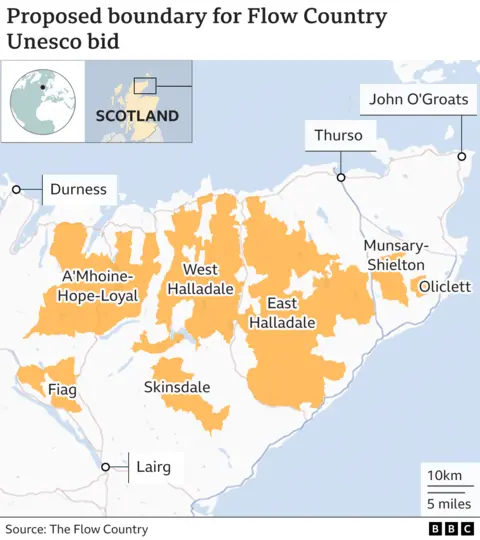

A bid for Unesco World Heritage status is to be formally submitted this early year, with a decision from Unesco expected in 2024.

Seven areas, amounting to a total of 469,500 acres of the Flow Country, would form the new site.

The designation would recognise the ongoing ecological and biological processes of the bog, as well as its biodiversity.

The idea of securing this status has been around since the late 1980s, but over the past few years The Flow Country Partnership has been leading work to secure local support for the formal bid.

The area is sparsely populated, with small communities around the fringes of the blanket bog. The nearest towns are Thurso and Wick.

Many of the residents earn their livelihoods from crofting and farming, while others works in tourism, at the Dounreay nuclear power complex near Thurso, or on offshore wind developments.

Heather Jardine

Heather JardineHeather Jardine, like many of the other residents, holds down a variety of different jobs. She is a crofter, hairdresser and holiday accommodation owner.

She lives in Strath Halladale, in the centre of the Flow Country, and supports the bid for Unesco status.

Her late father moved from England to work at Dounreay 60 years ago and he loved the area so much that he never left.

Heather shares his passion for the Flow Country and does not want to see a repeat of damaging activities on the peatland she witnessed in the 1970s.

"We are in the heart of nature here," she says.

"We cannot imagine not seeing all the stars at night and not being able to swim in clean rivers in summer."

Norrie Russell

Norrie RussellNorrie Russell has lived in Strath Halladale for 27 years, 20 of them managing RSPB Scotland's 52,000-acre Forsinard Flows national nature reserve, and then latterly in an advisory role working with local crofters and farmers.

He is also chairman of Halladale Hall and Amenities Association.

"One of the things I have always loved here is the strength of community," he says.

Norrie believes securing Unesco status could offer new opportunities in sustainable tourism and branding of local produce, while at the same time highlighting the environmental value of the peatland.

He says traditional livelihoods such as crofting and farming could continue as they are, adding that they already play a key role in providing grassland habitat for vulnerable species such as curlew.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNorrie says: "The landscapes themselves, I think, are incredibly special.

"They are not everybody's cup of tea, not everybody likes landscapes that are wide and open, but a huge number of other people will travel a long distance to spend time here."

He adds: "In the spring when the greenshank and golden plover are singing, it's a fantastic place."

However, there are others who have worries about the potential effect of the designation.

Willie Findlay has farmed on 3,000 acres near Melvich for almost 30 years. He has diversified into offering buggy tours of his farm, and says world heritage status could help bring more tourists to the area.

But he has concerns about possible negative effects on agriculture, and restrictions on developments such as wind farms.

Norrie Russell

Norrie RussellWillie, who farms 750 Cheviot sheep and 24 cows, says: "I already have 800 acres under sites of special scientific interest designations and I am quite restricted in the numbers of livestock I can have on those areas.

"I am concerned a world heritage site would also impose restrictions."

Dr Steven Andrews, Flow Country world heritage project coordinator, says it was acknowledged during public consultations there were big concerns around perceived new restrictions.

But he says most people would not notice any change to their lives on a day-to-day basis.

"World heritage will bring no extra restrictions on agriculture or crofting," he says.

"What Unesco require is protection to already be in place. The boundary we have come up with is already covered by the highest level of protection you can give it, 73% of it is covered by that."

Steven, who grew up on the margins of the Flow Country, hopes Unesco can help raise the profile of the Flows and other peatlands.

"It is a bit of an enigmatic landscape, as many peatlands are. They are difficult to access and I think that is one of the biggest challenges," he says.

"This is about helping people understand their value."

Steven adds: "The Flow Country has been neglected to a certain extent, though the people who live in and around there understand it.

"It is so important these peatlands are understood and by sharing it would mean a lot to me and, I think, it would mean a lot to local people."

Norrie Russell

Norrie RussellWWF Scotland and RSPB Scotland are among those watching the world heritage bid closely.

Ruth Taylor, agriculture and land use policy manager, says: "The Flow Country is Europe's largest blanket bog, a huge carbon store and a precious habitat for many rare plant and animal species.

"Declaring it a Unesco World Heritage site would recognise just how important our peatlands are, and the benefits they can bring for the environment and local communities."

Ben Oliver Jones, site manager of RSPB Forsinard Flows, said the designation would be recognition of an important landscape and an accolade to those who live and work there.

He added: "World Heritage site status for the Flow Country would shine a brighter light on peatlands globally, prompting fresh efforts to conserve, restore and research these landscapes in other parts of the world."