The Scot who helped build Oppenheimer's atom bomb

BBC

BBCAs war raged across Europe in 1942, a team of scientists on the other side of the Atlantic were brought together to work on a top secret project - the development of an atomic bomb.

The Manhattan Project was led by the United States but a number of prominent British scientists were transferred to work on it, including Scottish physicist Sir Samuel Curran.

A new film about the development of the first nuclear weapons - Oppenheimer - follows the life of the nuclear physicist who was the director of the laboratory that designed the bombs - J Robert Oppenheimer.

Although Curran does not make an appearance in the film he was part of a team that worked on an important aspect of the project - the separation of isotopes of uranium.

The atomic bomb would not have been possible without the process, which today is called uranium enrichment.

The team's leader, American nuclear physicist Ernest Lawrence, is played by Josh Hartnett in the film.

Universal Pictures

Universal PicturesCurran was born in Ballymena, Northern Ireland, in 1912 but moved with his mother to live in Wishaw, North Lanarkshire, shortly after his birth.

He studied mathematics and natural philosophy at the University of Glasgow, followed by a PhD on research into methods of detecting radiation.

From there he went to the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge to study, where he met nuclear pioneer Ernest Rutherford, who would die later that year.

Rutherford had taught Oppenheimer some years before and was described as the "the father of nuclear physics".

It was under his direction that students would become the first to split the atom in a controlled manner.

When an atom is split a huge amount of energy is released and it is this reaction which makes nuclear weapons possible.

US Air Force Museum

US Air Force MuseumOn the outbreak of World War Two, Curran joined the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) and worked on the development of radar and the proximity fuse for explosives which proved instrumental in the destruction of German V-1 rockets.

In 1940 he married fellow colleague at the RAE Joan Strothers, a physicist who he had first met while at Cambridge.

Early in 1944 they went to the Radiation Laboratory at Berkeley in California to work on the Manhattan project which was already under way.

While there, Curran invented the scintillation counter, a device similar to a Geiger counter which is used in laboratories around the world to this day to detect ionizing radiation.

What was the Manhattan Project?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 1939, US President Franklin D Roosevelt received a letter from German physicist Albert Einstein warning that Germany might be trying to build an atomic bomb.

The Manhattan Project was the code name for the American-led effort to develop its own nuclear weapon, starting in 1942.

Research and production took place at more than 30 sites across the US, UK and Canada.

The project's weapons research laboratory was located at Los Alamos, New Mexico, and that was where the bulk of the project's research was conducted, under the direction of Oppenheimer.

On 16 July 1945, the world's first atomic bomb was tested at the Trinity site in the New Mexico desert.

Less than a month later the US dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, followed by another on Nagasaki just three days later. Thousands died in the devastation.

The Japanese Emperor Hirohito broadcast a surrender message to his people via radio on 15 August and later a peace treaty was signed ending the war.

Terrible loss of life

Scottish historian Sir Thomas Devine talked to Curran before he died in 1998.

The physicist told Sir Tom that they had no idea how far along the Germans were with their atomic project so they felt it was vital to build the bomb before the Nazis did.

Sir Tom said: "He much regretted the terrible loss of life in Japan but insisted dropping the bomb was essential to ending the war in the east."

After the war, Curran returned to Scotland to work at the University of Glasgow despite being offered a post at the University of California.

Although the success of his university department gained it an international reputation, Curran left in 1955 to work on the development of the British hydrogen bomb.

Much later in life he told former MP Tam Dalyell that he did not agonise as much as others about his part in making the hydrogen bomb possible.

"But I did wonder where the ultimate results of my work and that of my colleagues would lead," he said.

Returning to Glasgow, Curran turned his attention to training the next generation of scientists and was invited to become the principal of the Royal College of Science and Technology.

Under his leadership it was merged with the Scottish College of Commerce to become a university - the first new one in Scotland for almost 400 years.

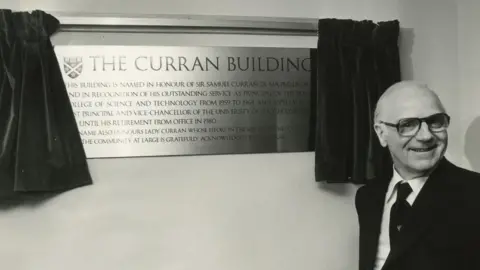

University of Strathclyde Archives OP/5/42/6

University of Strathclyde Archives OP/5/42/6"It was enormous for the birth of the new University of Strathclyde to have a scientist of his eminence at the helm," Sir Tom said.

In the early 1990s he interviewed Curran, who had remained principal until 1980, and described him as "a man of gravitas and intellect" but without "pomposity or side".

"He did not do much research in his later years as a university principal but his record of scientific eminence before then speaks for itself," he said.

Curran died in 1998. That year his wife Joan - a talented and accomplished scientist in her own right - unveiled a plaque in the Barony Hall in Glasgow in his honour.

Two things in life especially angered him, according to an account of his life on the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography website.

The very low salaries paid to scientists by comparison with businessmen and the failure to recognise how science and technology had helped to win WW2.