The workers who saw Scotland's ferries saga unfold

BBC

BBCThe workers at the Fergusons shipyard had a clue that something was about to happen when they arrived for work on an August morning in 2014.

The previous night someone had spotted the intricate scale models of ships which had been built at the yard during its 112-year history being loaded into the back of a van.

What they suspected was a change of ownership - but the news was far worse.

The yard was in administration. They had an hour to gather their belongings and leave.

"The guys were just shell-shocked," recalls welder John McMunagle

"All of a sudden your whole world's upside down. I saw grown men who had never had another job, just Fergusons, standing and crying.

"And you're worrying: 'How are they going to cope? What are they going to do? Where are we going to go here?' There was nowhere to go."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFerguson shipyard in Port Glasgow had a significance that went far beyond the number of people working there.

The last commercial shipyard on the Clyde was a beacon of skilled employment in one of Scotland's most hard-pressed communities.

"Talk to somebody in your family, or anybody, there's always somebody's working in Fergusons, whether it's your dad, your uncle, your granda, your cousin," said plater Alex Logan, who has worked at the yard since he 16.

A week later the future looked brighter as Alex took an early morning phone call from Jim McColl.

He asked Alex and John, both conveners for the GMB union, to meet him at Glasgow Airport, adding: "Contrary to what you're reading in the newspapers, I'm taking over your shipyard."

PA Media

PA MediaJim McColl was one of Scotland's foremost businessmen, a member of Alex Salmond's council of economic advisers with a track record of turning around failing businesses. He bought the yard a week before the Scottish independence referendum.

Workers were soon taken on again with a 5% pay rise provided they gave up their morning tea break. A contract was awarded to build a small CalMac ferry while plans were made to bring the yard into the 21st Century.

The following year the shipyard's rebirth seemed to take another spectacular leap forward with an order for two much larger CalMac ships. They were destined to become famous for all the wrong reasons.

"We had a meeting. Jim McColl, Nicola Sturgeon. And Jim had everyone gathered round. Said we've got a big order," recalled Alex.

"We thought the future was going to be really good. Really good."

But amid the relief, Alex Logan was also worried.

"When I found out the size of the ships and the way we were going to do it was build the two side-by-side…

"I've worked in there a long time. In my opinion it was impossible for us to build two ships that size side-by-side."

When concerns were raised, the yard's new managers insisted they had a plan.

"It was just a case of 'You're here to work for us. We'll do it'," said Alex.

Work on the two huge ships got under way in far from ideal conditions as brick Edwardian buildings were being demolished as part of the yard's modernisation.

It soon became clear there was a bigger problem - they were being asked to construct ships when the design was nowhere near complete.

"If you're a plater or a fabricator and you look at the drawing, and you've been building boats all your days, and you can see, that doesn't look right. That's a bit light for the steelwork for where it's supposed to be going," said Alex.

"And you question that and it's just: "That's the plan, that's the drawing. You just build, you're no here to think. You just build'."

Government ferries agency CMAL and Jim McColl's firm FMEL blamed each other for what has been described as a "catastrophic" failure.

The workers soon found themselves in the middle of a bitter stand-off.

"We knew there was a kind of poisonous atmosphere going on, between CMAL and FMEL's senior management," recalls fellow shop steward John McMunagle.

"We were well aware of that... the gunfight at the OK Corral was going on."

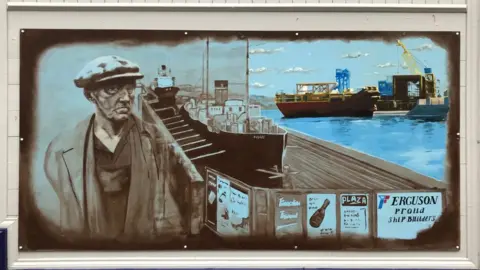

In a walkway at Port Glasgow station there is a painting celebrating the town's shipbuilding past. In one corner a sign reads: "Ferguson - proud shipbuilders."

As years slipped by and the build foundered, that pride was being sorely tested. The ships are still being constructed now, five years late and massively over budget.

Alex said the workforce realised how damaging it was for the people in the island communities who were waiting for the ferries to be delivered.

"These ferries are still languishing down at the shipyard. It's embarrassing to us that we haven't got as far as we should've got."

Despite differences with Jim McColl's management team in the early days, the workers retained a good relationship with the businessman himself, even as the yard headed back towards administration in 2019.

With potential Ministry of Defence contracts being talked about, he still painted a vision of a Clyde shipbuilding revival that could employ hundreds of skilled workers, breathing new life into Port Glasgow.

"If he'd have achieved it, he'd have been a hero in the town. Sadly, it didn't come to any fruition," reflected John.

Robert Perry

Robert PerryThe deadlock finally persuaded the union reps that nationalisation was the best option for saving jobs.

Government-appointed troubleshooter Tim Hair won some early goodwill by offering permanent positions to many staff who for years had been on temporary contracts - but it soon felt like another false dawn.

"Our concerns started growing when there were more, as we call it, management team planners, whatever you call them, grey hats, every week. There was more and more and more people coming on site," said Alex.

John added: "We brought it up at every board meeting. 'Why is this happening? We just can't believe what's happening here, we've got managers everywhere. We can't get steelworkers'."

BBC Disclosure has learned that matters came to a head in November 2021 when the workforce informed the board and senior management team they no longer had confidence in them. A new chief executive, David Tydeman, was appointed earlier this year.

After years of setbacks there appears to be a fragile sense of optimism returning, not least among the 54 apprentices now working at the shipyard.

Nathan Wyllie, 19, is being trained as a plater.

"You do see a lot of folk coming in who maybe don't see as much potential in the yard," he said.

"But certainly within here, when you see all the guys on the shop floor, you do get a sense of security that we will get these ships and future orders done."

Kirsty Graham, 23, has completed her apprenticeship and is now a full-time employee.

"It's a great opportunity in here - it's like a community... there's so much skill for the future," she said.

The first of the two ships, Glen Sannox, is due for delivery next spring. The new boss hopes completion of the second ship, still known only as hull 802, will be a smoother journey, demonstrating to potential customers that the yard has turned a corner.

"It will give us a fighting chance to rebuild the great reputation we did have, because we did have a great reputation - delivering in time, on budget, with a good quality," says John McMunagle.

As he approaches retirement, he believes Ferguson is in a better place now than it has been in many years.

"What a legacy it would be to leave a yard that is thriving.

"We know we're capable of doing it. It's just having the right leadership."

Reporting team: Mark Daly, Kevin Anderson, Calum Watson, Katie McEvinney

Mark Daly investigates what went wrong at the Ferguson shipyard, and raises questions about the tender process that saw the contract awarded in 2015.