'Milly would be here' had Glasgow hospital followed advice

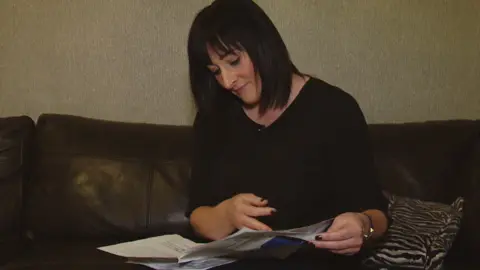

Kimberly Darroch

Kimberly DarrochA mother whose daughter died at Scotland's largest hospital has said her daughter would be still alive had concerns about water contamination risks been addressed in time.

Kimberly Darroch was speaking after a leaked inspection report into Glasgow's Queen Elizabeth University Hospital (QEUH) revealed "high risks" in 2015.

Milly Main, 10, contracted an infection in 2017 while on the hospital campus.

She was recovering from leukaemia at the Royal Hospital for Children.

The QEUH 2015 inspection report, which ranked infection control measures as "high risk" in several areas just two days after the hospital opened, was passed to Labour MSP Anas Sarwar by whistleblowers.

The hospital stayed open despite the warnings but has since had to close some wards for a time due to the risks from the water.

NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde (NHSGGC) insisted the hospital campus had a "safe and effective water supply" and all inspection reports had been acted upon.

Ms Darroch told BBC Scotland on Thursday night: "I'm shocked with the information that came out today. The fact that they've known since since 2015, it's absolutely disgusting that nothing was done about it and no action was taken and the hospital was still opened.

"I believe Milly would still be here if action had been taken. I've no doubt in my mind that Milly would be sitting beside me, right now.

"There is no words to describe that pain of knowing that if things had been different, that if things had been sorted with the water, she would still be here.

"I think the health board needs to be held to account for the mistakes that they made."

She added: "We wouldn't have been made aware of any of this if it wasn't for the whistleblower coming forward.

"I think there will continue to be shocking revelations for the foreseeable future."

A spokesperson said the Scottish government was "examining in detail" the separate material Mr Sarwar had highlighted.

They added: "We want to ensure that all families who have been affected can get the answers that they are clearly entitled to and the health secretary has given her personal assurance that she will ensure this happens.

"We are committed to making sure that these matters are dealt with transparently and with clear accountability, which is one of the reasons the health secretary has instructed a public inquiry in these matters to be chaired by Lord Brodie."

Ms Darroch said she was "very angry" and felt the health board had swept the case "under the carpet".

A hospital complaints manager had contacted her on Thursday but she had not received an apology, she said.

Milly, who had leukaemia, underwent a successful stem cell transplant in July 2017 and was making a good recovery when the following month her Hickman line, a catheter used to administer drugs, became infected. Milly went into toxic shock and died days later.

Her death certificate lists a Stenotrophomonas infection of the Hickman line among the possible causes of death but Ms Darroch says the family were kept in the dark about a potential link to contaminated water problems at the hospital.

A spokeswoman for NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde said: "We are very sorry for the ongoing distress that has been caused to Ms Darroch and we want to provide parents with as much support as possible.

"We are in contact with Ms Darroch and would like to meet her to answer her questions if she would be happy to do that."

In the Scottish Parliament, Mr Sarwar said he had seen figures which suggested there were 50 cases of infections at the Royal Children's Hospital - part of the £842m QEUH campus - between 2015 and 2018, and a further 15 unconfirmed cases so far this year.

Pressed on the warnings at first minister's questions, Nicola Sturgeon said she was determined to get the "answers parents deserve".

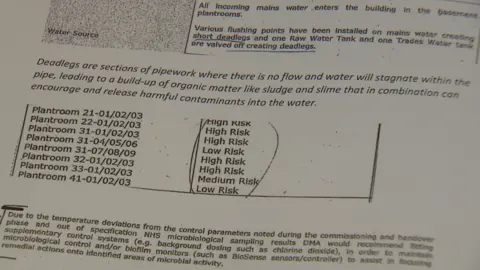

The documents seen by Mr Sarwar show that NHS Estates commissioned three separate independent reports into the water supply at the QEUH.

The first Legionella assessment, carried out by private contractor DMA Water Treatment on 29 April 2015 - two days after the hospital welcomed its first patients - categorised the management of the bacteria as "high risk" because there was "significant communication issues between the parties" responsible for managing the risk.

The problem of contaminated water is one of a number to beset the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital (QEUH) and the adjoining Royal Hospital for Children.

Last year, two cancer wards at the children's hospital were shut because of concerns about infection, and children were moved to the QEUH instead. An inquiry by Health Protection Scotland later identified 23 potential water supply-linked infections during 2018.

In January it emerged two patients at the QEUH had died after contracting an infection linked to pigeon droppings.