Dalgety Bay: How do you clean all the sand on a radioactive beach?

Jacobs

JacobsThousands of radioactive particles have been found on the coastline at Dalgety Bay in Fife since 1990.

It is believed they came from radium-coated glow-in-the-dark components in World War Two aircraft that were incinerated and dumped there.

The radioactive contamination was first detected at the beach during routine monitoring.

Now a team of engineers are sifting through tonnes of sand and soil from the whole beach as part of a £10.5m project to remove all the hazardous material.

They are using a purpose-built scanner which has been assembled in a cabin on the shore to detect the radioactive particles.

The equipment was created by Jen Barnes, the radiometrics lead for engineering company Jacobs, which is cleaning the Fife beach.

"It's something I've put together, I've tested, I've developed - and it works.

"I feel a lot of satisfaction from that," she said.

Jacobs

JacobsDiggers scoop up sand and soil from the beach, which has been closed to the public while the work is carried out.

The soil is poured on to a specially designed conveyor belt which takes it into the cabin, where there are eight gamma detectors.

The system is designed to detect the tiniest particles buried underneath 15cm of soil on the conveyor.

The smallest radioactive particles which have been recovered measure less than 1mm by 1mm, smaller than a grain of rice.

When the conveyor belt stops, each detector scans the soil and sand for a few seconds.

Ms Barnes said: "It's like when the light spreads out from a torch. All the material on the belt is reached between all the detectors."

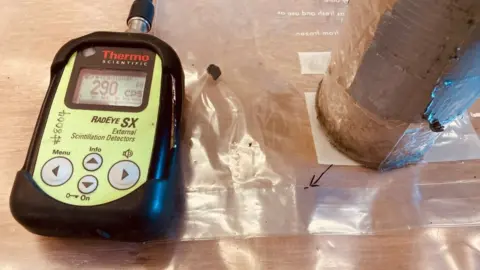

If a radioactive particle is detected, a handheld monitor is used to locate and remove it.

Only gloves and trowels are needed to remove the particle.

"The sand and soil is damp as it has come off the beach, so we don't need to worry about the material flying around," she said.

Jacobs

JacobsThe particle is placed into a metal tray and measured for radioactivity, before being put into a labelled sandwich bag.

This is then placed into a waste drum inside a locked store. Each month a 200 litre drum containing these bags of particles is sent to a licensed disposal company.

The team, which stops work during the winter to allow nesting birds on to the beach, scans about 100 square metres of beach a day.

So far 3,200 particles have been retrieved from the beach.

There are about three months of work left during the project, which will resume next April.

By the end of the work, the team will have dug up, scanned and replaced 264,860 cubic feet (7,500 cubic metres) of the beach - the equivalent of three Olympic swimming pools.

Jacobs

JacobsSite manager Stephen Jackson said the work they were doing was "a bit different and a bit special".

"I think what we're doing is going to make things better for the local community," he said.

The radioactive contamination was first detected at the beach during routine monitoring in the 1990s.

Previous attempts to tackle the contamination had been hampered by disagreement between the Ministry of Defence, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (Sepa) and Fife Council over who was responsible for the contamination.

The MoD was formally named as the polluter by Sepa, Scotland's environment watchdog, but the work continued to be hampered by delays.

However, in May 2021 Sepa announced that final permits had been issued to allow the project to begin.

Jacobs

JacobsJen Barnes told BBC Scotland it was important work.

If nothing was done, there was a risk that people using the beach could receive a dose of radiation which exceeds the safety limits.

She said surface monitoring had been taking place since the 1990s, but this was reactive rather than proactive.

"When they found something they picked it up and have removed it.

"But rather than just keep doing that, it was decided the best thing would be to completely try to remediate the site."

She said the project had been "quite challenging" at the start, but would be "satisfying" when it was completed.