SNP budget may go down in left-leaning history

Getty Images

Getty ImagesJohn Swinney's budget was devolution in action.

Scotland already had more generous welfare payments than other parts of the UK, as well as state-funded access to prescriptions, tuition fees, and personal care for the elderly.

It has also been striking its own public sector pay deals, avoiding at least some of the industrial action which has hit the NHS elsewhere in the UK.

The divergence continued with the budget statement by the deputy first minister in his role as acting finance secretary, covering for Kate Forbes who is on maternity leave.

She was probably glad not to be there, for the first few minutes at least.

The event began badly amid a row about a leak to the BBC, with Mr Swinney and his boss, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, summoned to see the presiding officer Alison Johnstone who wanted to know what was going on.

Proceedings were delayed for more than half an hour and, when they resumed, from the press gallery it was hard to hear Ms Johnstone at times as she was drowned out by angry opposition MSPs, to her obvious irritation.

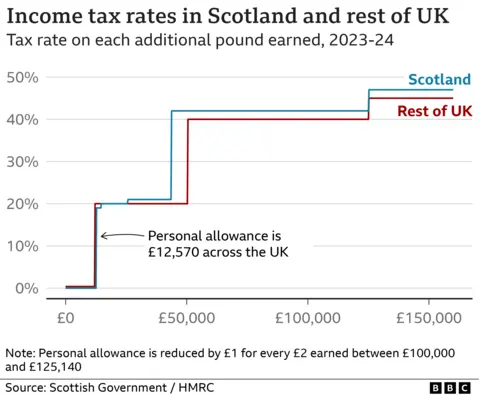

That row will pass but Mr Swinney's budget statement will be remembered for pushing Scottish income taxes further away from those in the rest of the UK.

Or, to put it another way, it may go down as the moment when the SNP leant a little further to the left — and a lot further than at some points in its history.

Decades ago, when the party drew much of its support from rural Scotland and competed with Conservatives in Angus, Perthshire and the like, critics often maligned the nationalists as "Tartan Tories."

After devolution in 1999 the party moved onto urban ground, taking votes from Labour in Scotland's old industrial heartlands, most notably in Glasgow and Dundee.

Even then some socialists accused it of timidity, of aping Tony Blair's New Labour by embracing the capitalist consensus.

The heart of the constitutional debate

Now Mr Swinney has gone some way to addressing that criticism by placing what he calls the "social contract" at the centre of the SNP project, stressing that while middle and higher earners are paying more in Scotland than are those elsewhere in the UK, Scottish taxpayers on the lowest wages are paying less than those in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Whether that decision was born out of ideology or necessity is an interesting point to ponder.

The tax and welfare powers of the devolved Scottish state have expanded since the opening of the Scottish Parliament 23 years ago, as illustrated by this very budget.

But, crucially, Holyrood has very limited borrowing powers, leaving Mr Swinney forced to consider tax hikes, spending cuts or a combination of both, to balance the budget.

Which brings us, inevitably, to independence.

A string of recent polls have suggested that there is currently a majority of voters in Scotland who want to leave the UK.

Supporters of independence say the country could do much better with the full range of powers available to independent nations.

Opponents say it would be an economic disaster.

As it happens, both sides point to the cost of living crisis as evidence for their case — and in that sense this budget, which above all is designed to respond to the economic emergency, is already at the heart of the constitutional debate.