Scottish independence: How will indyref2 compare with 2014?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDust off the placards. Unpack the soapbox. Grab your cagoule.

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has fired the starting gun in another referendum campaign — so here we go, right?

Not so fast.

Many supporters of independence describe the run up to the 2014 poll - when Scotland voted to stick with the UK by 55% to 45% - as exhilarating and optimistic. Plenty of their opponents recall feelings of exclusion and sadness.

Either way, it is hard to deny that politics came alive that year. For a while the nation crackled with energy as campaigners for and against independence debated poverty and pensions in the nation's parks and plazas.

Some of that enthusiasm persists in regular pro-independence marches and the occasional show of solidarity for the union but the nation is no longer in full-on campaign mode.

And even if the Scottish government is able to persuade the UK Supreme Court of its right to hold a referendum - a long shot according to some eminent legal scholars - an exact repeat of 2014 does not seem very likely.

Too much has changed.

For a start both teams, for and against independence, have splintered.

Labour's reputation was damaged by standing shoulder-to-shoulder with the Conservatives in the Better Together campaign to keep Scotland in the Union. It is very hard to imagine such a cross-party coalition being formed again.

Getty Images

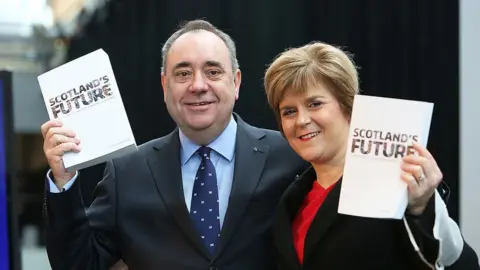

Getty ImagesTheir opponents in the Yes Scotland camp have fallen out too, about vision, strategy and tactics, a divide most obvious in the rift between Ms Sturgeon and her predecessor Alex Salmond who now leads a separate pro-independence party, Alba.

It's not just the players who have evolved since 2014 though. So has the script.

A pandemic, a cost of living crisis, war in Ukraine and Brexit have all scrambled the discourse about Scotland's future.

While the UK voted to leave by 52% to 48% Scotland voted to remain by 62% to 38%.

The first minister contends that being removed from the European Union against Scotland's will strengthens the democratic case for independence. Scotland is "not a region questioning its place in a larger unitary state" she argues but "a country in a voluntary union of nations".

Of course many of her opponents contend that Brexit weakens the economic case for independence on the grounds that if Scotland were readmitted to the EU it would have to erect a hard border with its largest trading partner — England.

Leaving that aside for a moment though, what about the fundamental principle? Does Scotland in fact have a right to leave the Union?

In her 1993 memoirs The Downing Street Years Margaret Thatcher, Conservative prime minister from 1979 - 1990, appeared to accept that it did, writing:

"As a nation, [the Scots] have an undoubted right to national self-determination; thus far they have exercised that right by joining and remaining in the Union. Should they determine on independence no English party or politician would stand in their way, however much we might regret their departure."

The current Tory Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who draws heavy criticism from many Scottish voters for both his policies and his morals, has taken a different tack, repeatedly insisting that now is not the time for another referendum.

But Ciaran Martin, the former senior UK civil servant who negotiated the Edinburgh Agreement which formed the basis for the 2014 referendum, now professor of government at Oxford University, draws a distinction between the political argument for Scottish self-determination and the legal case.

"The Supreme Court can absolutely say there's no mechanism to consult the Scottish people on independence without Westminster's consent," says Prof Martin.

However he adds, if Downing Street refuses to describe another path for Scotland to secede "you have to give up the pretence that this is a voluntary union, that Scotland is allowed to leave."

Of course it was not the Scottish people who hitched their wagon to England and Empire in the first place. The historian Prof Sir Tom Devine has described the Scottish nobles who took the decision as "the elite of an elite," an electorate representing 0.06 per cent of the population.

It is also true that the Scottish economy was in dire straits after the debacle of the Darien Scheme, a disastrous attempt to establish a colony on the isthmus of Panama which links Central and South America, and bridges the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Nonetheless there was a vote in the Scottish Parliament and the nobles did indeed choose union, which took effect on 1 May 1707.

Gradually this United Kingdom grew even closer - trading together, building an empire together and fighting wars together.

But long before anyone had heard the word Brexit the relationship was under strain.

In the 1960s the US and the UK stationed nuclear weapons on the Clyde, less than 30 miles from Glasgow, bringing jobs but also generating moral outrage.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the 1970s North Sea oil boomed. Energy firms made fortunes and the UK Treasury raked in millions in taxation. But with most of the UK's oil off Scottish shores its discovery fuelled a nationalist movement which wanted all Scots to share in the spoils.

The 1980s were the decade of Mrs Thatcher, a Tory prime minister supported by most English voters but rejected by most Scots. Her decision to pioneer the controversial poll tax in Scotland combined with her strategy of forcing old industries to change or die drove many Scottish voters into the arms of her political opponents.

Even the arrival of the devolved Scottish Parliament in 1999 did not "kill nationalism stone dead" as Labour's George (now Lord) Robertson had hoped it would.

Instead support for independence remained more or less steady and eventually began to rise.

"The parliament took a lot of the sting out of being Scottish and that was really good," said the writer and commentator Fiona Rintoul, "but it set up a scenario where if there was a different government in Westminster...there was going to be a clash."

The decline of the Labour party is a key feature of Scottish politics in the 21st Century, arguably both symptom and cause of the rise in nationalist sentiment.

Reuters

ReutersChris Deerin, Scotland Editor of the New Statesman, argues that in the later years of Tony Blair's 1997-2007 premiership the SNP under Alex Salmond spotted that Labour was becoming fatigued and pounced.

"In a sense they were offering a like-for-like replacement to the Labour Party," he said, but further to the left and "more optimistic."

This shift was accelerated by Mr Blair's decision to join the United States in invading Iraq which was "the final straw" for some Labour activists in their move towards embracing independence, according to Mr Deerin.

He remains persuaded that there is a strong case for Scotland to stick with the Union, involving the "common sense" redistribution of resources within the UK and a seat at the top tables of international institutions but he also worries that Britain has become a "transactional" affair, weakening its attraction.

Ms Rintoul sees Scotland drifting away from its neighbour, and approves of the direction of travel.

"A result of 45% of people voting to completely overturn the status quo in a non-wartime situation is not a ringing endorsement for the status quo," she said, adding that since then Brexit and the pandemic have meant that "Scottish politics has completely decoupled from British politics."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe turmoil of the past few years has certainly reshaped the debate about Scotland's future.

It has generated thorny questions about currency, borrowing, benefits and borders, tax and trade, nuclear weapons and energy.

Of course there are options for Scotland other than independence and the Union.

After 2014 the Scottish Parliament's tax and benefits powers were expanded and a Labour commission led by the former prime minister Gordon Brown is currently considering whether to go even further, perhaps even advocating a federal UK.

For now though, 315 years after the Union was formed; 25 years since Scotland voted for devolution; and eight years on from choosing to remain in the UK, it's independence which still dominates the national conversation.

It's just not clear at the moment if or when that conversation will spill out onto the streets in another full-on campaign.