How well have Scotland and the UK coped with Covid?

It is time to "show our beautiful smiles" again says Katerina White, a café owner in the Scottish city of Perth.

She is delighted that from Easter Monday Scotland's legal requirement to wear face masks in public places is being lifted.

Sitting outside her dog-friendly Brew and Chew café, Ms White tells me it has been a tough two years, economically and emotionally - and she's anxious to move on from Covid.

Keeping her three cafes and restaurants in the city going through lockdowns and other restrictions has been immensely challenging, she says.

Even when they could open, restrictions meant fewer tables, a reduced menu and shorter opening hours.

Is Ms White personally worried about the virus any more?

"Not really," she says, pointing to the widespread take up of vaccines and to the fact that we don't use lockdowns to deal with other public health threats.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTo many observers, Scotland's First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has epitomised caution in her handling of the pandemic, often bringing in restrictions slightly earlier than Prime Minister Boris Johnson in neighbouring England and retaining them for rather longer.

England's final mask mandate, for instance, was lifted nearly two months ago on 24 February.

Polls suggest that while Ms Sturgeon has fallen from dizzyingly high approval ratings at the height of the emergency she remains much more popular in Scotland than Mr Johnson, who these days is more likely to be heard championing individual freedom than collective caution.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhich approach was best? That is a difficult question to answer.

At this stage assessing any nation's pandemic performance is tricky and involves many caveats. It's not just lockdowns and other restrictions which matter. Population age and density, vaccination rates, and many other factors make a difference.

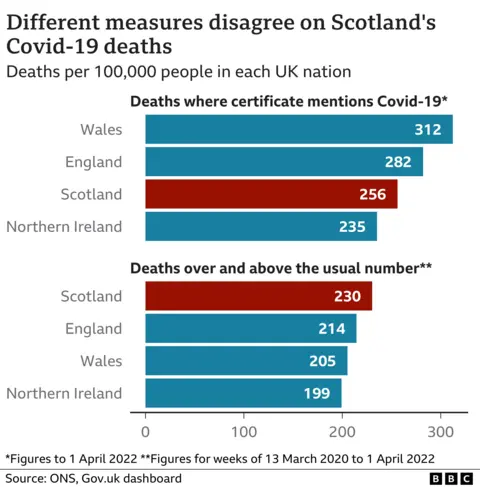

Plus different datasets tell different stories.

Throughout the pandemic, for every 100,000 people living in Scotland, 256 died with Covid listed on the death certificate, according to the Office for National Statistics.

That set of figures seems to suggest Scotland outperformed Wales and England but not Northern Ireland.

However, if we examine all deaths over and above the pre-pandemic average - such as those linked to cancer, heart disease and dementia - and not just those directly attributed to Covid, then Scotland is the UK's worst performer, with 230 excess deaths per 100,000.

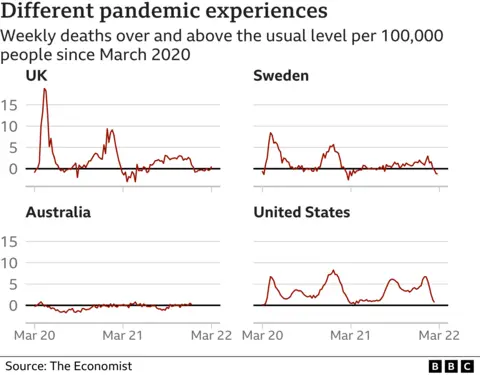

Look further afield though and you can argue that policies and outcomes in the different UK administrations were actually relatively similar.

Take Sweden. In the first wave it became the poster-country for a libertarian approach to tackling Covid, with its public health chief Anders Tegnell refusing to impose the type of lockdowns being deployed elsewhere.

That decision remains hotly debated, and Stockholm's Covid policies have since changed several times, but Sweden currently emerges from an international comparison of excess deaths modelled by the Economist in better shape than the UK (although considerably worse than its Nordic neighbours) with 133 excess deaths per 100,000.

At the other end of the policy scale were countries with much tighter restrictions such as Australia which, as my colleague Nick Bryant has written, took an early decision "to pull up the drawbridge and shutter the portcullis".

Well there, and in New Zealand which also took an isolationist approach, deaths were actually below their normal level during the pandemic - although the figures for Australia only cover the period up to the start of this year.

On the other hand, many other countries have seen far higher levels of death than the UK. The United States, for example, has an estimated 342 deaths per 100,000.

Nikos Kapitsinis, an assistant professor of economic geography at the University of Copenhagen, has studied patterns of excess deaths.

He suggests that as well as public policy, underlying factors should be taken into account when assessing national performance.

Countries demonstrating low excess mortality were more likely to be wealthier with adequately-funded healthcare systems and a high number of medical beds per capita, Prof Kapitsinis told BBC News.

That echoes recent concerns from within healthcare about NHS resilience, including an estimate last month by the Royal College of Emergency Medicine that 240 patients had died in Scotland unnecessarily because of A&E delays since the start of the year.

Remember though that these data only tell you so much. Public policy is by no means the only, and possibly not even the defining, factor in how any country coped.

There is one final - and major - caveat to this attempt to rank pandemic performance. The virus is still with us, as the current outbreak in Shanghai in China vividly demonstrates.

And for many people, including mother-of-two Charmaine Dodds, it will never truly be over.

On 2 April last year she lost her husband Lee to the virus, days after his 32nd birthday.

He had not yet been invited for his first vaccine appointment but apart from having asthma she says he was strong, fit and healthy.

Mrs Dodds is full of praise for the doctors and nurses who treated Mr Dodds at Ayr and Crosshouse hospitals but she has questions and queries about the quality of his care before he was taken in, specifically asking why it took six days from the moment he first sought help to his being admitted to hospital.

"I've got to cuddle my kids to sleep every night crying for their dad," she says.

"You're trying to grieve, but you're trying to help your children as well and trying to put on a brave face. I think that's what hard."

Mrs Dodds is worried about ending all legal restrictions now and in some respects she thinks Ms Sturgeon was not cautious enough - blaming a decision to reopen the nursery where she worked last Spring for her family contracting Covid in the first place.

"I feel quite nervous knowing the fact that everywhere is opening up," she adds.

In a statement, NHS Ayrshire & Arran said patient confidentiality meant they could not comment on individual cases, adding "we would encourage anyone with any concerns about the care or treatment provided to contact us directly".

In the months to come the decisions taken by politicians, scientists and doctors will be examined in detail as public inquiries begin to ask how well we coped with Covid.

For now though, Scotland is picking up pace again and the state - which reached into our lives like never before in peacetime - is retreating, returning some measure of freedom to the individual.