The mystery of Anthrax Island and the seeds of death

Getty Images

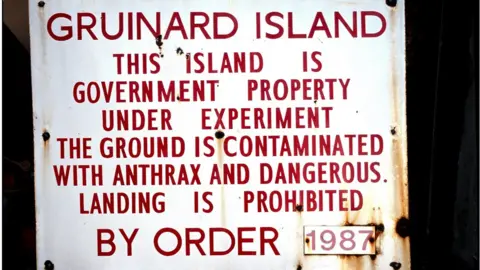

Getty ImagesFor decades, Gruinard Island off the north west coast of Scotland was too dangerous to allow public access.

It was known as "Anthrax Island" after it was contaminated during World War Two by scientists carrying out germ warfare experiments.

Anthrax is a lethal bacteria, especially when inhaled, and it proves fatal in almost all cases, even with medical treatment.

The secret wartime experiments left the tiny island uninhabitable for decades - until in 1981 a group known as the Dark Harvest commandos launched a move to focus attention on the deadly contamination.

It began with a letter to the Glasgow Herald newspaper, which said: "By the time you read this the campaign will have started in earnest.

"The first delivery will have been made - and where better to send the seeds of death than to the place from whence they came?"

That place was the Porton Down biological research centre in Wiltshire, the top secret Ministry of Defence laboratory.

The facility was searched and nothing was found. So they searched again and found a bucket of soil near the perimeter.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe letter claimed the soil contained Bacillus anthracis, better known as anthrax, a deadly agent of germ warfare.

The government scientists quickly worked out it came from 600 miles away on Gruinard Island.

Gruinard had long been uninhabited when World War Two led to an influx of soldiers to the north west Highlands to carry out secret preparations.

In 1942, with the war on a knife edge, Prime Minister Winston Churchill feared the Nazis had developed a biological bomb. So he tasked his team of top scientists with finding a way of harnessing anthrax as a weapon.

They had to find a testing site that was remote, uninhabited and isolated but accessible from the mainland.

Nobody across the bay in small settlements such as Laide knew what they were doing but rumours began to spread as sheep, cows and horses began dying strange deaths.

Indelible Telly

Indelible TellyThe facts about what actually happened remained a source of mystery until the declassification of an extraordinary MoD film 50 years later.

It showed about 80 sheep being put in exposure crates facing the anthrax cloud.

The men conducting the experiments wore cloth overalls and hair protectors as well as respirators and gloves.

The film shows a small blast set off by remote control and then white powder moving on the wind.

"This tiny moment, this puff of powder, is releasing death," author Cal Flynn tells the documentary.

Within days all the sheep were dead.

Infected carcasses were incinerated or buried under tonnes of rubble when a cliff on the island was blown up.

The experiment was deemed a success and the scientists returned to Porton Down - but the anthrax remained.

PA Media

PA Media

In order to keep people on the mainland quiet, the government paid compensation for the dead livestock, blaming the infections on the careless disposal of animals from a Greek ship.

In another attempt to rid the island of anthrax spores, Porton Down dispatched two men to Gruinard to set fire to the heather.

By the evening, locals across the bay could see a huge plume of smoke over the island.

Churchill's anthrax bomb was never used.

By the end of the war, Gruinard had been poisoned, burned and abandoned.

It remained off limits and it was not until 24 years after the experiment that the warning signs even mentioned anthrax.

Porton Down experts checked the soil but the anthrax spores were "surprisingly resistant to degradation".

The Dark Harvest Commandos wanted action. They blamed the continuing problem on "40 years of official indifference".

PA Media

PA MediaFour days after bringing the bucket of soil to Porton Down they struck again, this time targeting the Conservative Party conference in Blackpool.

A tin box believed to contain soil from the anthrax island was left at Blackpool Tower.

Unlike the first sample, this one turned out not to contain anthrax but the authorities were on high alert.

Attempts were made to find the culprits. Police believed it must be someone in the local community.

Det Insp Colin MacDonald was one of the officers tasked with finding out who but he was met with a wall of silence.

"I felt there was maybe more known in the community than was being said," he tells the documentary.

Suspicion fell on a range of anti-nuclear activists, fervent Scottish nationalists and people living alternative lifestyles, but no arrests were ever made.

PA Media

PA Media

On 7 December 1981, the Dark Harvest pinned a final letter to the door of the UK government's Scottish Office HQ in Edinburgh.

Instead of threats, the letter declared that the aims of their protest had been met and there would be no further action - for now.

As mysteriously as they appeared, the Dark Harvest commandos disappeared.

If their aim was to highlight the continued contamination of the island, they had succeeded. They also hastened its clean-up.

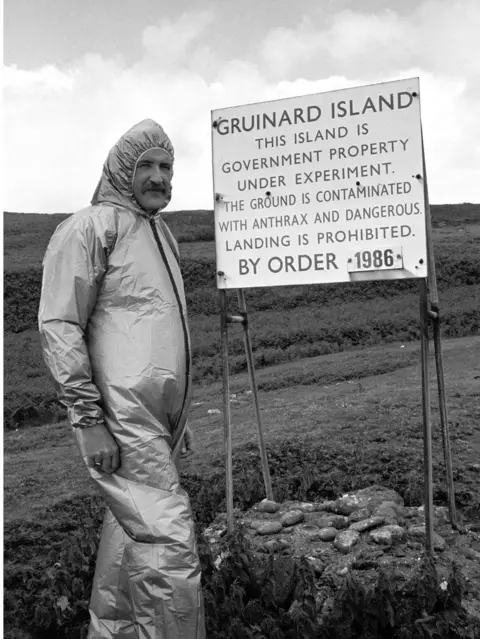

In 1986, Gruinard was again a hive of activity as teams of scientists, vaccinated against anthrax and dressed in protective clothing, prepared to return the island to its natural state.

They sprayed the soil with seawater and formaldehyde and it was again tested at Porton Down.

Finally, on 24 April 1990, the MoD declared Gruinard anthrax free.