Covid in Scotland: Hospitals under more pressure than ever, say medics

BBC

BBCScotland's hospitals are under more pressure than ever, doctors have told BBC Scotland.

While the number of Covid patients has fallen, the NHS is trying to catch up with surgeries and treatments put on hold during the first wave of the pandemic.

But more people are also being admitted with other complex, more advanced disease, having put off seeking treatment.

It's leading to long waits in emergency departments and piling pressure on capacity in other parts of the hospital.

As the Scottish government prepares to publish a Covid recovery plan for the NHS, medics at Glasgow's Queen Elizabeth University Hospital spoke to BBC Scotland's health correspondent Lisa Summers.

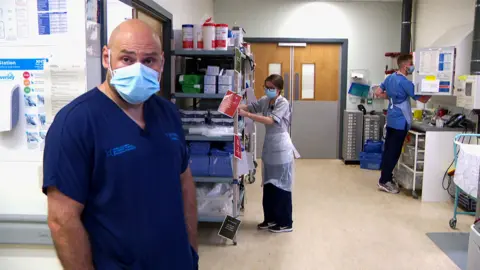

It's 10am on Tuesday at the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital. The emergency department is full. Five seriously ill patients are in resus, all 16 assessment cubicles are occupied. Some have been waiting more than 12 hours for a bed to become available elsewhere in the hospital.

Dr Alan Whitelaw, a consultant in emergency medicine who heads up the department, says: "The demand is something I have never seen before, it is busier than the Queen Elizabeth has ever been in its six years of existence."

It is a similar picture in other emergency departments. Data published this week by Public Health Scotland shows nationally just 78.7% of patients were admitted, treated or discharged within four hours, and 182 people spent more than 12 hours in an A&E.

Dr Whitelaw says the pressures in the emergency department are a reflection of how stretched the NHS is, with very few beds available in other parts of the hospital.

"Lying on a trolley for a number of hours anywhere is unpleasant, it also turns the tension up, everyone is waiting and everyone is not as satisfied as they otherwise would be," he says.

"It's a very difficult place to come and work just now. It's very tiring, very draining, stressful and you can see that on the staff on a day-by-day basis."

Other parts of the hospital are equally busy. Staff are still treating Covid patients but in far fewer numbers. Instead, they are seeing many more patients who have more complex and advanced disease.

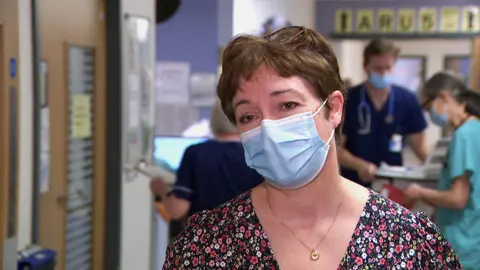

Helen Dorrance, a senior surgeon who specialises in cancer, has more than 20 years' experience but says the last 18 months have been the most difficult of her career.

"The waiting times for clinics and for investigations like colonoscopy and endoscopy and for day surgery in particular are huge at the moment, so I have no idea when we are going to be out of this other than it is not going to be any time quickly," she says.

It is very hard knowing that delays in starting treatment have led to worse outcomes for some patients, she adds.

"It makes you very sad for the individual, sometimes angry. It's very difficult knowing that had an individual come six months earlier then the discussions might have been different, the outcome for them and for their families might have been completely different."

At the start of the pandemic, it was care-of-the-elderly wards which were the first to be turned into Covid wards.

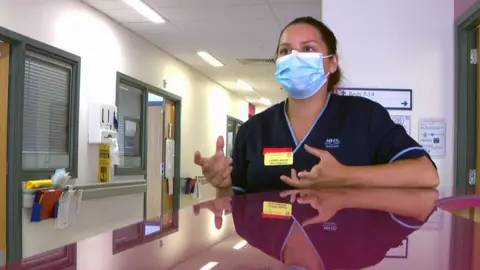

Senior charge nurse Lauren Johnson says staff had to adapt quickly to wearing PPE and communicating with sometimes confused or hard-of-hearing patients who were scared and couldn't see their families.

"It's a blur, it really is," she says. "The five months I worked on the Covid hub was so difficult, I didn't see my family.

"I get emotional just talking about it, just seeing our wee frail patients not getting the chance for their families to say goodbye sometimes, and we were the ones saying goodbye to them, it was really, really difficult.

"It was the hardest thing I've ever had to deal with in my life."

There are 244 care-of-the-elderly beds at the Queen Elizabeth, most of them are back to treating non-Covid patients, but all of them are occupied.

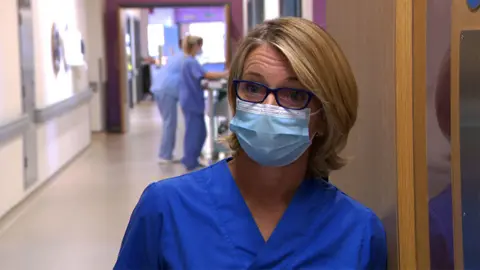

Clinical lead and consultant in medicine for the elderly, Dr Lara Mitchell, says the patients who come to them are also sicker.

"We are still full, we are still busy," she says. "The pandemic has been hard for all of us but it has been particularly bad for the older adult.

"They've not been connected with as many of their family and friends, they've not had ways to meet, so patients are not as strong as they used to be.

"All of that impacts on their general health when they have other medical issues going on, and I think that is what we are seeing, a lot of deconditioning as well as late presentation of illness because people have held on at home."

A spokesperson for the Scottish government said they recognised the additional pressure NHS staff were facing, and were in daily contact with boards facing the greatest challenges.

"We are delivering record funding of more than £16bn in 2021-22 to support NHS Scotland and its heroic staff through the most challenging period in history - and after careful and extensive consultation we are currently finalising our NHS recovery plan which will set out plans to increase inpatient, day-case and outpatient activity," they added.

Getting the health service back on track is going to be a huge challenge. Spending on healthcare already amounts to about half of the entire Scottish budget, and there have been long-standing difficulties recruiting staff.

Outside the emergency department, four ambulances are parked up. They are waiting with patients onboard until there is room in the department. It means four less ambulances on the road.

Social distancing rules limit numbers in the waiting room and a queue has formed outside. A nurse is patiently explaining the pressures today and helping patients work out if they would get better treatment elsewhere.

Dr Whitelaw says: "If you've got what you perceive to be a life-threatening condition you should absolutely come to the emergency department, whether that is by 999 ambulance or getting here yourself.

"I think if you've not got what you think is a life-threatening condition you should access NHS 24 on 111 rather than just coming to an emergency department, because demand currently exceeds supply and we are full today."