Drug deaths in Scotland reach new record level

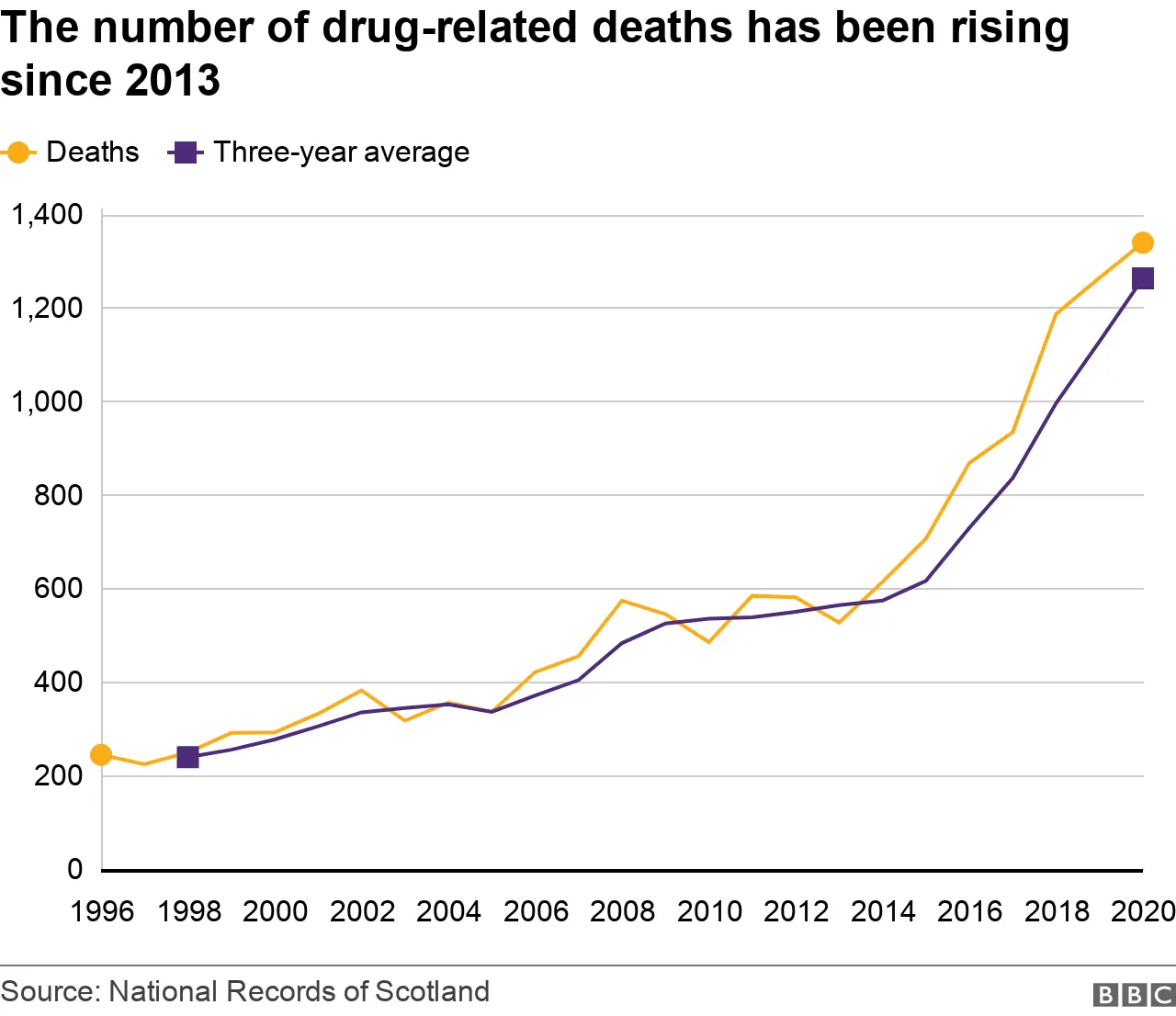

More than 1,300 people died of drug misuse in Scotland last year, with the country seeing a record number of deaths for the seventh year in a row.

The annual figures showed that there were 1,339 drug deaths last year - an increase of 75 from the 1,264 recorded the previous year.

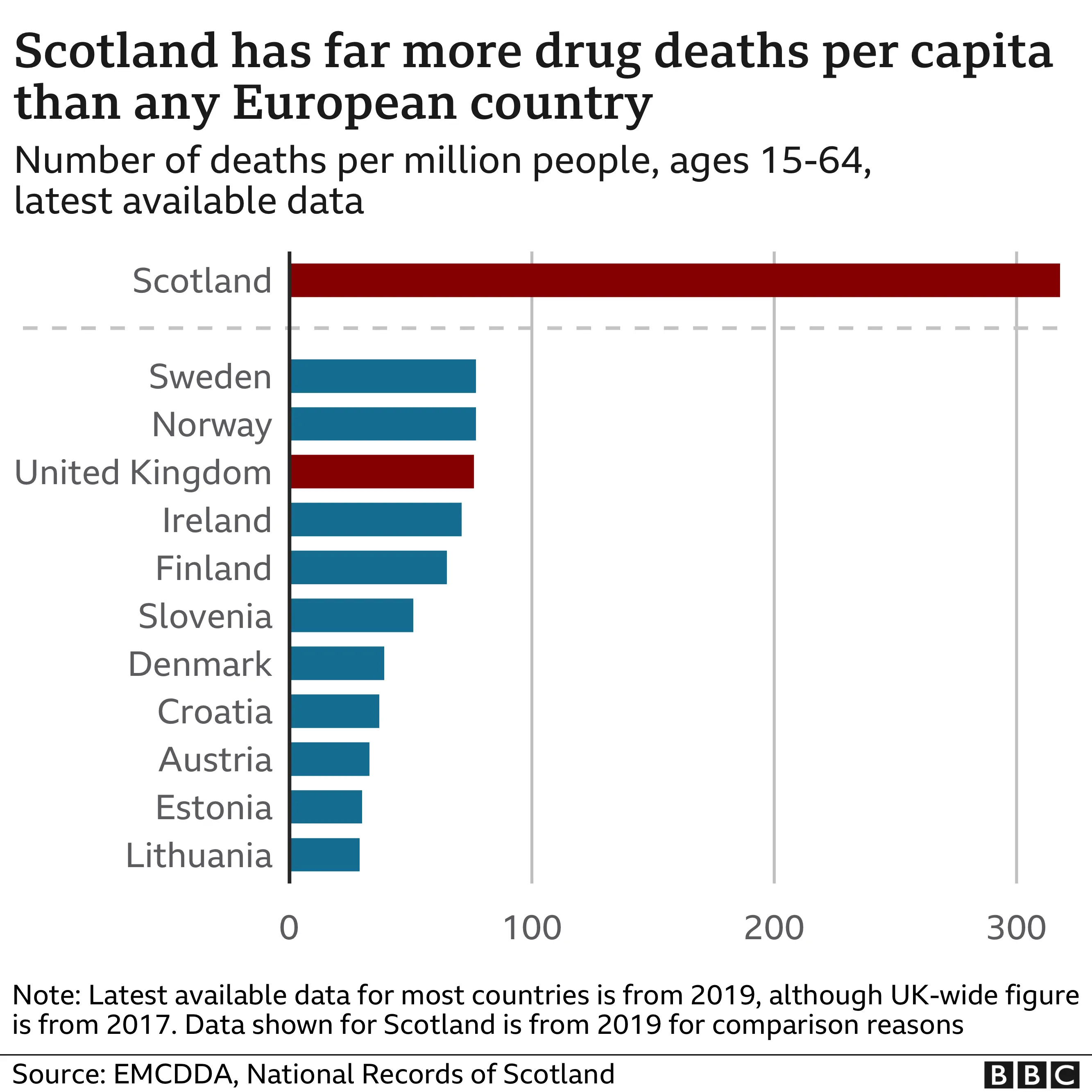

It means Scotland continues to have by far the highest drug death rate recorded by any country in Europe.

And its rate is more than three-and-a-half times that of England and Wales.

The number of drug-related deaths has increased substantially over the past 20 years and is now almost three times higher than it was a decade ago, with the upward trend accelerating since 2013.

Men were 2.7 times as likely to have a drug-related death than women last year, after adjusting for age.

Almost two thirds of the deaths were of people aged between 35 and 54, with the average age increasing from 32 to 43 over the past two decades.

Greater Glasgow and Clyde had the highest rate of all health board areas at 30.8 deaths per 100,000 people, followed by Ayrshire and Arran and Tayside with rates of 27.2 and 25.7 respectively.

And people in the most deprived parts of the country were 18 times more likely to have a drug-related death as those in the least deprived.

The gap has widened significantly since the start of the century, when deaths were 10 times higher in the most deprived areas.

Some 93% of the deaths reported in 2020 were as a result of accidental overdoses, while 4% were considered deliberate self-poisoning.

The figures showed 1% of deaths were as a result of long-term drug abuse, while 2% were undetermined.

More than one drug was found to be present in the body of 93% of those who died, suggesting that many of the deaths were caused by Scotland's "polydrug" habit - mixing dangerous street drugs with alcohol and prescription pills.

Opiates such as heroin and methadone were implicated in 1,192 deaths while benzodiazepines such as diazepam and etizolam were implicated in 974.

Gabapentin or pregabalin were present in the bodies of 502 people who died, and cocaine in 459.

There have been large increases in the numbers of deaths where "street" benzodiazepines, such as etizolam, were involved in recent years, from 58 in 2015 to 879 last year.

The fake Valium - that sells for as little as 50p - is many times stronger than prescription drugs, and is often taken alongside other drugs such as heroin.

Three people a day. The highest rate in the UK and in Europe. Looking inwards, a four-fold increase in Scottish drug deaths since the start of the century.

And yet, the shock may lie in how much everyone had grimly predicted yet another record year.

The pandemic undoubtedly affected addiction services but no one is arguing that, if it hadn't been for Covid, Scotland's drug problem would be solved.

Poly-drug use is rife. Those succumbing will mix methadone prescriptions with heroin. They will then take benzodiazepines - likely so-called street Valium counterfeit pills pressed by gangsters and flooding communities at 50p a pop. All of these things come together to slow a person's breathing until it stops.

And the poorest are worst hit - those living in a deprived community are 18 times more likely to die of an overdose than those in more affluent areas.

How does Scotland tackle this? The Scottish government hopes the investment of £250m into innovations such as Naloxone - the overdose reversal drug - and alternatives to methadone may turn the oil tanker around, but it may take time.

New treatment standards for addiction services should also have an effect, though questions remain over why these hadn't been in place before.

There is a clamour for more radical action now - calls for rights to recovery, more investment in rehab services and big questions for the UK government at Westminster too, over the effectiveness of its 50-year-old Misuse of Drugs Act.

But overall, there is now a bitter acknowledgement that those accessing these health services were for too long neglected and underserved. That acknowledgement will be of little comfort to the families of the lost.

Opposition parties say cuts to drug rehab and addiction programmes by the Scottish government have had a big part to play in the upward trend in the number of deaths in recent years.

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has previously admitted that the number of deaths was "indefensible" and "a national disgrace", and that her government had not done enough to tackle the problem.

The Scottish government has pledged to spend an extra £250m over the next five years in an attempt to reduce the number of deaths, including £20m a year on increasing the number of residential rehabilitation beds across the country.

The Scottish Drug Death Taskforce, which was set up in 2019, has also been working to increase the distribution of Naloxone, a medication that can reverse the effects of an opiate-related overdose.

Almost two-thirds of ambulance crews are now able to distribute it to people who might need it, and to train them in its use.

Responding to the latest figures, Ms Sturgeon tweeted that the number of lives lost to drugs continued to be unacceptable.

She said the government "does not shirk the responsibility" and is determined to make changes that will save lives, but said the figures predate the actions it had set out at at the start of the year.

Public health minister Joe Fitzpatrick lost his job shortly after last year's figures were published, with Ms Sturgeon creating a new post of drugs minister for Angela Constance.

Ms Constance said the latest figures were "heart-breaking" and that the government was "working hard to get more people into the treatment that works for them as quickly as possible".

She also announced that data on suspected drug deaths will be published quarterly from September of this year, to "ensure we can react more quickly and effectively to this crisis and identify any emerging trends".

Ms Constance and Scottish Conservative leader Douglas Ross both attended a vigil in Glasgow on Friday that was held to commemorate those who have lost their lives to drugs.

'I give back to society now'

Kane Duffy, from Edinburgh, has stayed clear of drugs for the last 14 years.

He started using heroin when he was 14 and was on a methadone prescription until his early 30s.

The 44-year-old broke free from drug use after a stay at the NHS-funded Lothian and Edinburgh Abstinence Project (Leap).

He now works as a specialist therapist at the Castle Craig rehab clinic.

He said: "All the time that I had taken from services, everything I was prescribed, every time the police had to intervene in my life… all of these things amount to a huge amount of money.

"I still don't like paying my council tax… but now I do pay my council tax. I pay my parking fines when I get them.

"I give back to society directly through the work I do and the taxes I provide. I don't cost the state anything now."

Mr Ross said a "united national effort" was now needed to tackle the drug deaths crisis, and called on Ms Sturgeon to back his party's proposal for a Right to Recovery Bill.

The bill, which has been developed with recovery and treatment experts, would enshrine in law that everyone can access the treatment they need, including a residential rehabilitation place.

Mr Ross said: "The drugs crisis is our national shame. It is a stain on Scotland that so many of our most vulnerable people have been left without hope, crushed by a system that is thoroughly broken.

"This is not a day for political posturing but it is a simple fact that the government's small steps are not cutting it. The crisis is getting worse and spiralling out of control."

Scottish Labour leader Anas Sarwar said the deaths were the "tragic consequences of years of failure to get to grips with this growing crisis in Scotland and to address the threat posed by drugs".

He added: "We have the same drugs laws as the rest of the UK but three-and-a-half times the rate of drugs deaths.

"We can and must act now, by investing in a range of services and delivering truly person-centred treatment and recovery."

And the Scottish Greens said the approach to drugs by both the Scottish and UK government was wrong, and said it was time to on restoring people's dignity and treating their addiction, rather than criminalising them".