Why did a Nazi leader crash-land in Scotland?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOne of the most bizarre episodes of World War Two unfolded on a farm to the south of Glasgow on 10 May 1941.

A German airman parachuted out of his Messerschmitt Bf 110 just before it crashed near Floors Farm in Eaglesham.

He was promptly arrested by a pitchfork-wielding local farmer who took him to his farmhouse before alerting the authorities.

The German identified himself as Captain Alfred Horn and demanded to see the Duke of Hamilton because he had an important message for him.

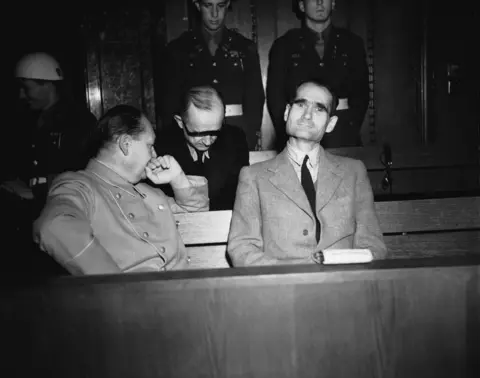

The next morning the duke, whose home was Dungavel House, about 12 miles from the crash site, was brought to meet the mystery airman who revealed himself as Rudolf Hess, deputy Fuhrer of The Third Reich, Adolf Hitler's long-time friend and ally.

Hess, who was positioned behind only Hermann Goering in the succession hierarchy of the Nazi regime, told Hamilton he wanted to broker a peace deal between Britain and Germany.

"Understandably Hamilton was a bit taken aback by all this," says Dr James Crossland, reader in international history at Liverpool John Moores University.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Why had a prominent Nazi flown for almost 1,000 miles on a solo mission over enemy territory in the middle of a war before coming down in a field in central Scotland?

And why did Hess have the mistaken belief that Hamilton wanted to broker a peace deal on terms acceptable to Hitler?

Dr Crossland said the strange nature of the story had led to some "enduring" conspiracy theories over the intervening years, including claims that the flight was promoted by a group in Britain wanting to overthrow Churchill and negotiate peace.

However, the historian says declassified documents point to Hess being misinformed about the level of support for a peace deal and embarking on a desperate flight of fancy.

In the early stages of the war there had been attempts by important intermediaries to make a deal but these had dried up after Churchill came to power in May 1940, Dr Crossland says.

Hess believed there was a blood bond between the British and the Germans and the common enemy was the Soviet Russians.

In the late summer of 1940 he asked his contacts if there were Britons who wanted to talk peace.

It was a friend of Hess's called Albrecht Haushofer who brought up the name of the unsuspecting Duke of Hamilton, whom he had met in Berlin before the war.

Haushofer wrote to Hamilton in order to make contact but never received a reply. It has since transpired that the letter was intercepted by MI5.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBy April 1941, Hess was desperate. He had been practising with his aircraft, waiting for Hamilton to indicate he was ready to talk.

He went back to Haushofer who told him there were still people who wanted peace.

Dr Crossland says Hess interpreted this as the go-ahead and made the fateful decision to fly to Britain.

"From Hess's point of view, the alleged existence of people who are dissenting towards Churchill's stance was enough to assume that these people were ready to overthrow Churchill and make a peace with Hitler," he says.

Dr Crossland says: "Hess was a very desperate man, he quite naïve, he was delusional and so for him this made all the sense in the world."

Why was Hess so desperate?

Dr Crossland says Hess was one of Hitler's earliest adherents. He served time with him in Landsberg Prison, following the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923.

"At one time he was possibly the closest thing Hitler had to a real friend," Dr Crossland says.

But by WW2 his star was waning within the inner circle of the Third Reich and he was often derided and made fun of by other leading figures.

"He did have a certain amount of desperation to reclaim the favour of Hitler," Dr Crossland says.

Dr Crossland says the official story is that this was a flight undertaken by a deluded man who got bad information and believed something that was not real.

He says conspiracy theories were borne of a period where there were gaps in the historical record but many of these have been filled by the declassification of papers which have pushed the burden of evidence towards the conventional reading of events.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter his arrest Hess was examined by Dr Henry Dicks whose first impression was of a "schizoid psychopath".

As their talks progressed, Dr Dicks was struck by Hess and Hitler's admiration of the British, despite Germany having the upper hand in the war at that time.

Dr Dicks thought an affection for the British may have been why Hess chose to make his solo flight to Scotland.

Hitler said he had no knowledge of what Hess was trying to do and the Nazi Party soon declared him insane.

In 1946, Hess was sentenced at the Nuremberg trials to life imprisonment. He died at Spandau prison in 1987, at the age of 93.

The fact that Hess was kept in the prison alone after other Nazi figures were released in 1966 led to assumptions that he was being held because they did not want his true story to ever get out.

However, files released in 2017 show the British government petitioned the Soviets on multiple occasions to release Hess.

"If there was something to hide about Hess's knowledge it does seem peculiar that the British government would want him released to tell his side of the story," Dr Crossland says.

He said that for scholars of WW2 the Hess story was "curiosity" but it merited no more than a couple of paragraphs in most historians' account of the war.

"It is enduringly bizarre and I engage with it on that level," Dr Crossland says.