Why are we building gas-powered ships?

PA Media

PA MediaThe two new ferries still being built in Port Glasgow have been making headlines for all the wrong reasons.

Glen Sannox and "hull 802" are the first UK-built ships capable of running off liquefied natural gas, or LNG, as well as conventional diesel.

They were once hailed as a step towards a greener future for Scotland's state owned CalMac ferry fleet.

But they are five years late, at least £150m over budget and have dragged Scotland's last commercial Clyde shipyard into administration, prompting nationalisation. And some have questioned just how "eco-friendly" they really are.

Was LNG the wrong choice - or a wise decision, poorly executed?

What is LNG ?

If you have a gas boiler or cooker in your home, you'll already be familiar with natural gas - which mainly consists of methane.

If you cool this gas to minus 162C it turns into a liquid occupying only 1/600th of its original volume.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) is much easier to transport and can be used as a portable fuel for ships or even trucks and cars.

But it is still a fossil fuel that produces carbon dioxide when burned.

Ending our reliance on natural gas in our homes is seen as a key climate change goal - so why are we building gas-powered ships?

A 'bridge' fuel on the journey to zero emissions?

Advocates of LNG argue it's less harmful to the environment than traditional marine fuels such as oil or diesel.

LNG engine manufacturers say they produce up to 30% less carbon dioxide than diesel equivalents.

But that doesn't take into account greenhouse emissions during extraction and transport of the gas.

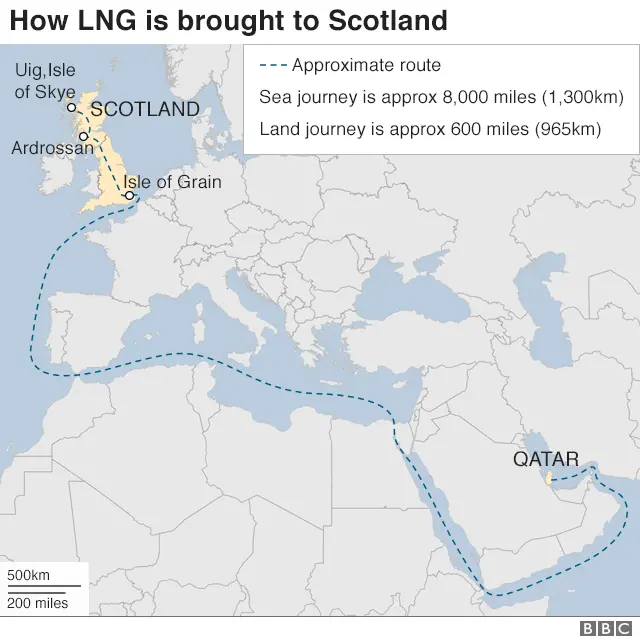

The UK currently has no facilities to liquefy natural gas so LNG would have to be imported - probably from the Gulf state of Qatar.

The LNG for CalMac's new ships first has to make an 8,000-mile journey by sea, arriving at the Isle of Grain terminal on the Kent coast.

It will then travel a further 460 miles by road tanker to Ardrossan in North Ayrshire or more than 600 miles to Uig on the Isle of Skye.

Together, the two ships would require between four and six road tanker loads of LNG a week.

There are other problems - methane, the main component of natural gas, is itself a greenhouse gas, 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

A small amount of this methane can pass through an engine unburned - something known as methane slip - and enter the atmosphere.

CMAL, the government-owned agency which owns the ships used by CalMac, says the latest engines minimise methane slip.

It also hopes Scotland will eventually have its own bulk LNG storage capacity, which would improve the overall carbon footprint.

NOx, SOx and other nasties

While the greenhouse emission benefits of LNG can be debated, when it comes to air quality there are clear benefits.

The smoke you see from a ship's funnel contains nitrogen and sulphur oxides - NOx and SOx as they're known - and other harmful particulates.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThese can contribute to global warming indirectly, but the main concern is their link to respiratory diseases and cancers.

Using LNG dramatically cuts NOx emissions and almost eliminates SOx pollution.

New legally-binding regulations, known as IMO 2020 kicked in on 1 January, requiring marine diesel to contain less than 0.5% sulphur.

Shipping firms have three main choices: switch to expensive low sulphur fuel, fit "scrubbers" to remove the pollutants from exhaust gases - or use alternative fuels such as LNG.

Scottish ferries have been using low sulphur fuel for years so they're already IMO 2020 compliant, but LNG offers further air quality improvements.

Is it a technically-difficult fuel to use?

The bulk tankers that transport LNG across the seas have been using it as a fuel for decades.

Even with powerful refrigeration, a small amount of LNG turns back to gas while it is being transported.

Shipping firms learned they could save money by burning this boil-off gas (or Bog as it's known) to drive their ships' steam turbines.

Since 2003 the Finnish firm Wartsila has been selling dual-fuel marine engines that can run off LNG directly, switching seamlessly back to diesel when required with no impact on performance.

This is the system used on CalMac's new ferries.

But while the technology isn't particularly new, it does pose extra design challenges compared to an all-diesel vessel.

CMAL

CMALA large cryogenic storage tank - like a giant chilled thermos flask - is required on the ship along with special refrigerated refuelling pipes.

While the technology has been around for some time, CalMac's new ferries are the first to be built in the UK. Design decisions have to be approved by insurers and regulators.

Major investment is also needed in infrastructure to supply the LNG to these ships (or "bunkering" - a term that dates from the days of coal when a ship's fuel was literally stored in a bunker).

The Scottish government plans to spend £5m on new LNG bunkering facilities at Ardrossan and Uig.

What about 'future fuels' like hydrogen?

There are currently several hundred LNG-powered ships in use or under construction worldwide, and that figure is rising rapidly.

But in the face of a "climate change emergency" some argue we should be looking at more radical zero-emission solutions such as hydrogen.

When hydrogen is used as a fuel - either burned in an engine or used in a fuel cell to generate electricity - the only by-product is water.

Before the ferry fiasco dragged it into administration, Ferguson Marine had teamed up with the University of St Andrews and others to develop a prototype hydrogen-powered ship.

The plan was to build a small ferry for the five-mile route in Orkney between Kirkwall and Shapinsay.

The turmoil at Ferguson hasn't helped that project - it is still in development.

Elsewhere, the Norwegian firm Norled has built what it claims will be world's first hydrogen ferry. They plan to start operating with hydrogen once supply issues have been resolved.

Norled

NorledHydrogen could work well for island communities like Orkney which have plenty of renewable energy sources.

The cleanest way of obtaining the gas is by splitting water molecules using electrolysis, a process which requires electricity.

Orkney is already using wind and tidal schemes to produce hydrogen locally - storing it in tanks and using it as a fuel for cars, or to generate electricity from fuel cells when it's needed.

For short routes, hydrogen could be carried on a ferry in compressed form rather than as a liquid.

But for longer journeys where more fuel is needed, there are technological challenges - storing hydrogen as a liquid requires temperatures of minus 260C.

A better solution may be to turn the hydrogen into ammonia, which is far easier to store in liquid form - a German firm is developing engines that could run on ammonia.

Battery-powered ships

The world's first all-electric ferry, MV Ampere, began operating on a short route in Norway six years ago.

In the summer of 2019, the 197ft (60m) long all-electric "Eferry" Ellen went into service in southern Denmark, and can travel 25 miles (40km) between charges.

Adrienne Murray

Adrienne MurrayCalMac already operates the world's first seagoing diesel/electric hybrid ferries (three small ships, built at Ferguson shipyard).

They run for 40% of the time on battery power, before having to switch to diesel generators. The batteries are recharged from the mains overnight.

The main constraint is the weight of the batteries (more batteries, less cargo) and concerns over how long the batteries will last before they need replacing.

At the moment it is only an option for short routes, but as technology advances, battery-power looks set to become more common, either on all-electric ships or in hybrid systems.

Other "future fuels" such as hydrogen and ammonia are developing rapidly.

One ferry user group has suggested as an interim solution we should look at conventional diesels coupled with fuel-efficient hull designs like catamarans.

Pentland Ferries has recently taken delivery of such a vessel - MV Alfred, built in Vietnam at a cost of just £14m - but CMAL which procures ships for CalMac, says that would conflict with its remit of having ships interchangeable between routes.

The world's shipping industry seems to view LNG as a sensible, well-tested option. A recent study predicted that by 2025 60% of shipbuilding orders would involve LNG.

So it looks like shipyards will be building a lot more gas-powered ships - whether that will satisfy climate change concerns is another matter.