Has new alcohol law changed drinking habits?

Ministers are hopeful that new statistics will show Scotland's drinking habits have changed after a new law pushed up the price of cheap, high-strength alcohol.

It is a year since the introduction of a minimum price for drinks depending on how many alcohol units they contained.

Public Health Minister Joe Fitzpatrick said he was proud that the government had implemented the measure.

He was hopeful figures would show there had been a "positive impact".

There were 1,235 alcohol-related deaths in Scotland in 2017 and almost 35,500 hospital admissions.

The Scottish government introduced minimum unit pricing in May last year in a bid to cut consumption and save lives.

Mr Fitzpatrick said: "I'm really proud to be part of the government that introduced minimum unit pricing - the first in the world."

He told BBC Scotland that new data on the effect of the policy was due to be published in mid-June.

"I'm very hopeful that this will show that there has been a positive impact," he said.

"Anecdotally I'm hearing from a number of people who have changed their drinking habits and there's some anecdotal evidence to suggest that when the evidence comes out in June, it will be positive."

BBC Scotland's The Nine has spoken to people around the country about how they have been affected by the new drinking laws.

The students

First-year anatomy student Conor, 18, reckons he drinks about 20 units a week - mostly lager.

He supports minimum unit pricing but it has had little effect on his drinking habits. In fact, he drinks more than he did last year as he has embraced his new university life.

"You're young, you drink and I don't think that will ever change, no matter what law you put in place," he said.

Rebecca, 21, is in her third year of an international business degree.

She "pre-drinks" gin with friends before going to bars and clubs, as she finds it more affordable.

"I don't think it's affected me too much," she said. "It's affected more own brands and I wouldn't tend to buy them anyway."

Meanwhile, engineering student James, 21, said he had seen his friends switch from drinking cheap cider to "better quality" drinks.

"It's cut out the really cheap and unhealthy stuff, it's made that less of an option," he said.

"Obviously it's there if you really want to drink it but why would you when you can pay the same amount for better-quality alcohol?"

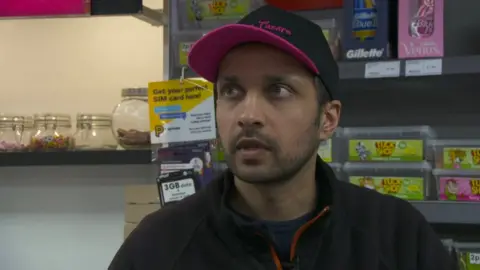

The retailer

Sachin Patel no longer sells Frosty Jacks cider in his shop in Muirkirk, Ayrshire, after its price rose from about £3.50 to about £11.50.

Customers refused to pay the increased price, instead opting for fruit ciders or even spirits.

Mr Patel said he could now match the prices offered by supermarkets, which used to sell spirits as "loss leaders" to entice customers into the store.

A bottle of Glens vodka used to be £9.99 - now he sells it at minimum unit price of £13.13.

"Because of that our profit margin is increased," he said. "That works better for us as retailers even if the volume we sell is less, the margin is greater."

He has concerns that the new law has led to an increase in violence against retailers.

"If someone wants alcohol, they're going to beg, borrow or steal," he said. "The retailers are taking the brunt."

But he is generally in favour of the policy.

"For us, it protects the retailers. It's helped people limit the amount of alcohol they consume because they're on a budget. On the whole I think it's a good idea."

The chronic drinker

Danny, 45, is an alcoholic who says he "drinks as much as possible" every day.

He said he has seen an increase in shoplifting since the new law pushed up the price of cheap drink. He can get a bottle of stolen vodka for £5 on the black market.

And he says he has to beg on the streets to feed his addiction.

"I don't want to say it's for a can of beer," he said. "You say it's for something to eat, some place for the night.

"Because they'll not give you the money because they'll say you'll spend it on drink, you'll spend it on drugs.

"And I'm not a bad person, I'm an alcoholic. I've got serious problems, issues inside and I consume the drink to help with the problems.

"But the price of the drink is ridiculous."