Is there a link between Scotland's exclusion rates and knife crime?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA spate of knife crime in England has been linked to an increase in the number of young people excluded from school. But in Scotland - where just five pupils were permanently removed from the classroom in 2017 - knife violence has fallen.

Why has Scotland's school exclusion rate dropped - and has it had a real impact on crime?

How many children are excluded from school in Scotland?

Official statistics show that more than 18,000 children were temporarily removed from their classroom in 2016/17.

Just five young people were excluded permanently or "removed from the register".

Exclusions of all kinds have dropped by 59% since 2006/07, when 44,794 children were suspended from school - 248 of them on a permanent basis.

The statistics relate to publicly-funded local authority schools in Scotland, not grant-aided or independent schools, or early-learning and childcare establishments.

However in England Department for Education figures show that permanent exclusions increased by 56% between 2013/14 and 2016/17.

The number of permanent exclusions across all state-funded primary, secondary and special schools stood at 7,720 in 2016/17.

Why has there been a drop in exclusions in Scotland?

Young people in Scotland can only be excluded from school in the most extreme circumstances.

And councils are duty-bound to provide a school education to all excluded pupils - whether that is in another local school, a school in a different education authority, or at an alternative location to school.

A spokeswoman for the Scottish government said: "We are committed to ensuring that all children and young people get the support that they need to reach their full learning potential with a focus on prevention and early intervention.

"Pupils are not 'removed from the roll' in Scotland and we expect children continue to receive an education while excluded, either at another school or alternative location."

She added: "Our approach to knife crime, also focusing on early intervention and prevention with young people, is recognised across the UK and internationally as making a real difference in keeping people safer."

How do schools deal with difficult students?

For many young people facing exclusion, their behaviour has been a "cry for help".

Meg Thomas, who works with schools in Glasgow and North Lanarkshire, said pupils can be communicating stress they are experiencing at home.

If they are excluded and sent back home, they return to that stressful place. It can also put them at risk of sexual and criminal exploitation.

Ms Thomas works for Includem, a third-sector organisation that supports young people in challenging circumstances.

She said that when students are at risk of exclusion, Includem often join meetings which are held with social workers, health staff, police officers.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThey try to uncover the root of the difficult behaviour, to help the young person understand the consequences of their actions and their own emotions.

She may discover that they have experienced trauma, witnessed domestic abuse or they undiagnosed health problems.

And it allows the school to understand how they can best help the student - without resorting to exclusion.

Ms Thomas says it is a system which works but Includem currently only works in a small number of Scottish local authority areas.

"We need to stop getting kids excluded because we know it mean they stop entering the criminal justice system," she said.

"If we put the money in the right place at the right time, it will have long term cost savings across Scotland."

Is there a link between school exclusions and knife crime?

Research by Edinburgh University academics has found that young people who were excluded from school were much more likely to be end up in the criminal justice system and prison.

But Prof Susan McVie, one of the authors of the Edinburgh Study of Youth Transitions and Crime, said the link with knife crime was less clear.

"There is a connection in the sense that people who are excluded from school are more likely to be involved in carrying weapons," she said.

They found that young people who carried weapons were twice as likely to be excluded from school as those who did not carry weapons.

"But when we looked at a whole raft of factors that might impact on whether people carried weapons, school exclusion actually turned out to be quite marginal," Prof McVie added. "It wasn't the most important thing in terms of explaining people's behaviour."

She said young people who self-harmed were more likely to carry weapons, as were those who were poorly supervised by their parents and those who felt socially-marginalised in their communities.

Although there has been a reduction in violent crime in Scotland and school exclusions, she said it was very difficult to prove a causal connection.

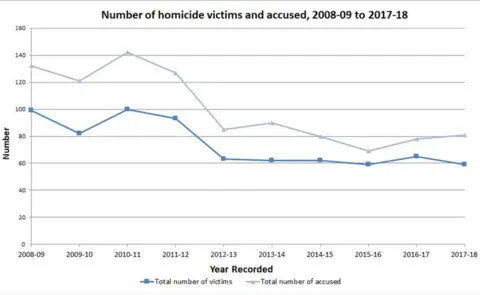

Justice Analytical Services

Justice Analytical ServicesAnd she suggested that Scotland's experience proved there was not one single solution to the apparent surge in knife crime in England.

"We have seen big reductions in violent crime in parts of Scotland where it was very, very high," she said.

"But it's worth also saying we've seen big reductions in violence where it wasn't very high. It not just what was done in Glasgow around the violence reduction unit that has been effective, there's a whole raft of things, of which reducing school exclusion was one.

"But better education, better youth work, better employment opportunities for young people - there's a whole raft of things and there's no one single solution."