Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the rooms that inspired Europe

BBC

BBCCharles Rennie Mackintosh was largely unappreciated in Britain during his lifetime but in Europe he was admired as a leading figure in avant-garde art and design.

While Glasgow was largely indifferent to the genius in its midst, in Vienna students transported Mackintosh through the city on a flower-strewn cart when he arrived for an exhibition of his work in 1900.

The 32-year-old Mackintosh was at the height of his powers and the Austrian city lauded the maverick designer and his new wife, Margaret Macdonald.

The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

The Hunterian, University of GlasgowThey were taking part in an exhibition by The Secessionists, a movement that wanted to break away from what they saw as old-fashioned forms of architecture and art.

They wanted clean, modern designs and were awestruck by the elegant arrangement of Mackintosh and Macdonald's Scottish apartment.

The brilliant white display included a tall mirror brought from their home in Glasgow, high-backed chairs that Mackintosh had designed for Miss Cranston's Tea Room and, above it all, two large friezes, depicting stylized long-haired women.

The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

Back in late Victorian Glasgow, designs and artworks by the couple were often seen as baffling.

In Vienna, Mackintosh was a major influence on many of the great avant-garde designers of the early 20th Century.

The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

One of the founders of the Secessionist movement, Josef Hoffmann, described Mackintosh as the leader of the modern movement.

The Glasgow couple also influenced leading Secessionist Gustav Klimt, who went on to create masterpieces, such as The Kiss.

McAteer Photograph

McAteer PhotographAs Mackintosh's home city celebrates the 150th anniversary of his birth, Toshie could not be more popular, with his face and his trademark motifs adorning everything from carrier bags to coffee cups.

He is now the epitome of Glasgow Style but he died 90 years ago in poverty-stricken obscurity after a career that ground to a halt in his early 40s.

The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

In the BBC documentary, Mackintosh: Glasgow's Neglected Genius, artist Lachlan Goudie says: "He was obsessive, he was visionary, he was a genius.

"He created in every building and every interior that he dreamt up a total artistic whole.

"Everything worked together."

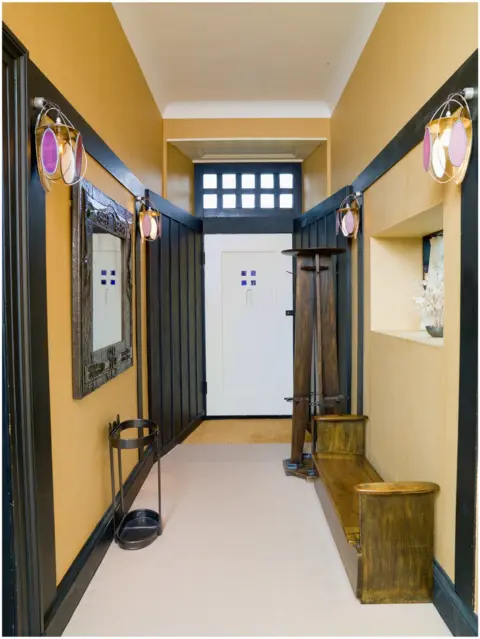

McAteer Photograph

McAteer Photograph McAteer Photograph

McAteer Photograph

These days Mackintosh's most famous architectural creation is his Glasgow School of Art building.

There was a national and international outpouring of grief when it was devastated by fire in 2014 and its magnificent library completely destroyed.

But when it was first unveiled in 1899, the half-finished building was deeply unpopular and appeared to lack symmetry and logic.

Outside a close circle of friends few knew about Mackintosh's architectural genius but his furniture designs were attracting an international following, especially in Austria and Germany.

Glasgow School of Art

Glasgow School of Art

McAteer Photograph

McAteer Photograph

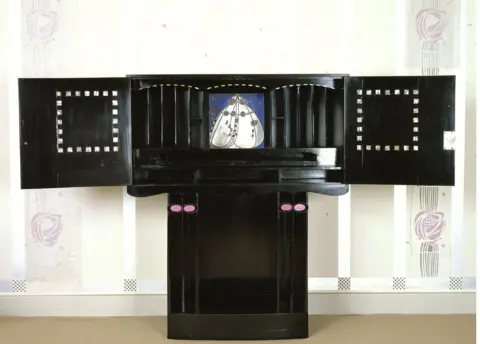

In 1900, Charles and Margaret, who had met at art school, married and set up home in Blythswood Street in the centre of Glasgow.

Their three rooms became a work of art as they developed their ideas in their own home.

The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

With grey and white decor, linen and muslin curtains, this was a world away from the fashions of the time which called for heavy oak furniture, picture frames and velvet drapes.

Photographs of their home were circulated across Europe in influential art magazines.

The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

When they later moved home they took their furniture with them, to Florentine Terrace in the affluent west end.

The house was demolished in the 1960s but Mackintosh's original furniture and designs were rehoused in a purpose-built museum just yards away.

BBC

BBCBack from Vienna, Mackintosh began work on a design for a "Haus eines Kunstfreundes" for a German competition.

It was never built at the time but 90 years later, when interest in Mackintosh had revived, his plans were realised in the House for an Art Lover in Glasgow's Bellahouston Park.

NAtional Trust for Scotland

NAtional Trust for Scotland

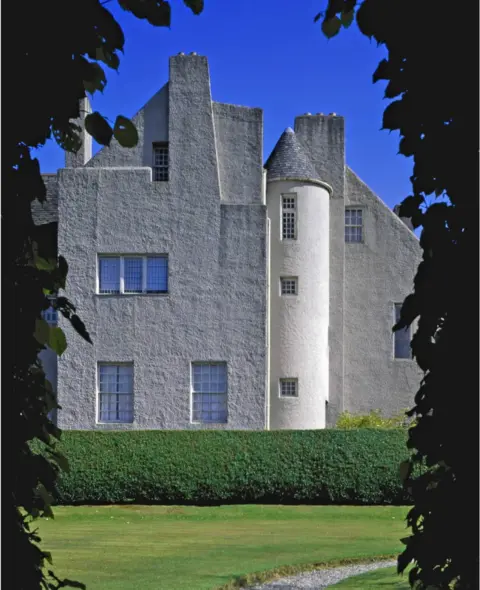

The closest Mackintosh himself got to building a similar creation was The Hill House in Helensburgh.

It was a family home with a difference, built in 1904 for publisher Walter Blackie.

On the outside, the house had solid massed forms with little ornamentation but inside the rooms exuded light and space, and the use of colour and decoration was all part of Mackintosh's uncompromising vision.

NAtional Trust for Scotland

NAtional Trust for Scotland

NAtional Trust for Scotland

NAtional Trust for Scotland

NAtional Trust for Scotland

NAtional Trust for Scotland

The architect was said to be a design dictator. He was also a fiery character prone to fits of rage.

But for all his faults, there was one wealthy patron who returned to Mackintosh time and again - Miss Catherine Cranston, the empress of Glasgow's tea rooms.

In 1896, she asked him to design a set of murals for her Buchanan Street premises.

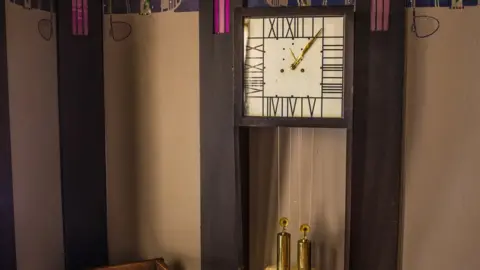

Two years later, for her Argyle Street tea rooms, Mackintosh produced a piece of furniture that would evolve into a design icon - his high-backed chair.

BBC

BBC

A close look at the chair reveals how the back legs change from rectangular to rounded and the oval headrest is sliced to suggest a bird in flight.

The high backs serve no purpose other than to make them stand out in a busy luncheon room and make the clients feel pretty special.

In 1903, Catherine Cranston asked him to design her fourth Glasgow tea room.

NAtional Trust for Scotland

NAtional Trust for Scotland

NAtional Trust for Scotland

NAtional Trust for Scotland

NAtional Trust for Scotland

NAtional Trust for Scotland

The famous Willow Tea Rooms was once Glasgow's ultimate house of splendour.

But after Miss Cranston was gone it became part of a department store and the Mackintosh's elaborate designs gathered dust behind the bathing suits and bridal wear.

The tea rooms have been refurbished at great cost and will be returned to their former glory for the 150th anniversary.

BBC

BBC

The Glasgow School of Art is also being refurbished after the 2014 and its library is being painstakingly rebuilt to Mackintosh's original design.

Mackintosh built a few other landmarks in Glasgow, such as The Martyr's public school, on the street in Townhead where he was born, Queen's Cross Church in Maryhill and Scotland Street School in Govan.

But by his early 40s, Mackintosh, who was said to have a "satanic" personality, was worn out and is thought to have had a nervous breakdown.

The Hunterian, Univeristy of Glasgow

The Hunterian, Univeristy of Glasgow

He resigned from Keppie and Honeyman and in 1914 he was in Suffolk to convalesce.

At the outbreak of World War One, Mackintosh was run out of the seaside town where he was staying because he was suspected of being a spy and he relocated to shabby flat in London.

NAtional Trust for Scotland

NAtional Trust for Scotland

Mackintosh struggled to get work and he took a commission working on a mid-terraced house at 78 Derngate in Northampton.

This was to be his last building design job.

NAtional Trust for Scotland

NAtional Trust for Scotland

In post-war Britain, outside a small band of supporters, Mackintosh was a penniless nobody.

In 1923, Charles and Margaret escaped to the sunshine of the South of France, where they lived a humble life.

Mackintosh concentrated on painting water colours of the landscape.

He was said to have considered it the happiest time of his life.

NAtional Trust for Scotland

NAtional Trust for Scotland

It was not to last, he was forced to return to London when he got cancer of the tongue.

He spent his last years unable to speak and died in Paddington in 1928, at the age of 60.

Mackintosh asked for his ashes to be scattered, not in Glasgow, but in Porte Vendre, where he had spent four happy years in the sun.

"The city that rejected him now plasters his image on everything from tea towels to fridge magnets," says Lachlan Goudie.

"The architect and designer who had slogged late into the night obsessing, probably would not have thought much of a Mackintosh microwave-proof travel mug."

On the 150th anniversary of his birth, Goudie says Mackintosh needs to remembered as an artist of global significance whose idea were mirrored across Europe.

All images copyrighted.