Meet the millennials: Who are Generation Y?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGeneration Y is the first generation in recorded history which is projected to be worse off than those which came before.

This week, BBC Scotland is looking at the lives of millennials and how they stack up next to the experiences of their parents and grandparents.

But who are the millennials?

In simple terms, Generation Y is the latest in a series of demographic cohorts which have been given slightly odd names in a bid to define them as a collective cultural group.

First there were the Baby Boomers, those born during a spike in the birth rate following the Second World War through to the early to mid 1960s.

The next demographic bump was Generation X, those born from the early to mid 60s through to the start of the 1980s; the "MTV generation".

Then we come to Generation Y, the millennials. Born from the early 80s through to the turn of the Millennium, this is a cohort which largely came of age at the outset of a global financial crisis, but also amid a vast acceleration in digital technology.

Incidentally the following generation, those born since the millennium, has in turn been dubbed Generation Z: the "digital natives" who have no recollection of a world without smart devices and broadband internet.

Philip Sim

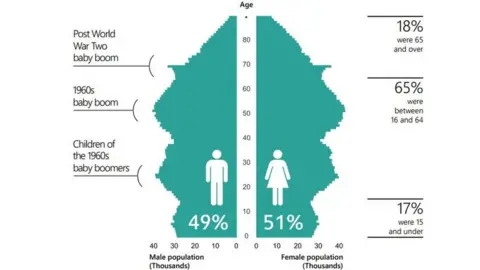

Philip SimScotland's National Records keep track of the country's population. They record more than 1.4m Scots residents who were born between 1980 and 2000, with slightly more women than men among them (a trend also reflected across the populace as a whole).

Starting from early life, Generation Y are more likely to stay on in full-time or further education than those who went before; the number of graduates more than doubled between 1984 and 2013.

Older generations were more likely to leave school at an earlier age, sometimes with no qualifications - something which is now very rare.

Only about 6% of 16 to 34-year-olds in Scotland have no qualifications at all; the figure for those aged 35 to 64 is more than double that, and for those over 65 it doubles again to more than a third. However those over-65s are much more likely to have other, non-academic qualifications.

Jobs market

After education, Generation Y are heading into an unpredictable jobs market. The employment rate is good, but many are in part-time work or self-employed, and they have faced the largest falls in real average earning in the wake of the 2008 recession.

According to the most recent set of labour market statistics, just over 71% of 16 to 34-year-olds are in employment, 5.7% are unemployed and 24.7% are economically inactive - many of them students or carers.

For those aged 35 to 64, the same figures are just over 77% employed, 2.9% unemployed, and 20.6% inactive.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut how good is the work?

Millennials in their 20s are 25% more likely to work part-time than members of Generation X were when they were at the same age. During their 20s, they are projected to earn £8,000 less than their GenX equivalents.

Much has been made of zero-hours contracts, a form of employment which has grown more common over the past decade; between 2003 and 2005 they sat at 0.4% of all contracts, UK-wide, but increased to 2.8% by the end of 2016.

Those on zero-hours contracts, where employers are not obliged to provide any minimum hours, are often young. According to labour market statistics released in May, a third of people on these casual contracts are aged 16 to 24.

Some people like the flexibility offered by a zero-hours contract, under which workers are not obliged to actually accept any work offered. But others see them as being exploitative and lacking in job and income security.

In Scotland, the most recent statistics list 2.2% of workers as being on zero-hours contracts, a figure which is the lowest on the UK mainland. The UK-wide figure rose from 2.5% to 2.8% in 2016, driven mainly by an increase in England from 2.6% to 3%.

Wages

People on zero-hours contracts are still paid the minimum wage, but the number of hours they work can vary to a large degree. The proportion of people in part-time or casual employment contributes to a significant disparity in average overall pay between generations.

In 2016, the median pay of Scots aged 18 to 21 was £200 a week. Those aged 22 to 29, who were more likely to be in full-time work, were paid £387 a week, and those aged 30 to 39, and thus more experienced in the labour market, £482.

The peak median weekly wage was for those aged between 40 and 49, at £494. Thereafter the figure falls back, with those aged 50 to 59 earning a median £470 per week.

A tougher employment scene makes it hard to get on the housing ladder - research by the House of Commons Library found that 59% of households led by a millennial are renting, with 38% owning their own home - whereas 20 years ago young people were more likely to own than rent.

There has also been a slight increase in the proportion of 25- to 34-year-olds who are still living with their parents - this is the case for 14% of millennials UK-wide.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGeneration Y is collectively a more diverse and socially liberal grouping than those who were born earlier; north of the border just under three-quarters of 16- to 34-year-olds identify as white Scottish, compared to over 80% of the older population.

However, they are also less likely to make their voice heard at the ballot box.

In the 2015 election, two-thirds of baby boomers voters turned out on polling day, compared to 56% of generation X and 46% of voting-age millennials.

This shifted somewhat in the snap election of 2017, when young people turned out in greater numbers - but they were still dwarfed by the proportions of older generations turning out.

YouGov found that 57% of teenage voters turned out in June, and 59% of those aged 20 to 24 - compared with 71% of those in the 50 to 59 bracket, 77% in the 60 to 69 cohort and a whopping 84% of those over 70.

Settling down

Those in Generation Y are far more likely to be single than those amid older generations.

Almost 80% of Scots aged 16 to 34 have never been married, compared to only about a sixth of those older.

This is not just because they have had less lifespan in which to meet a partner and settle down - people are getting married later and later in life.

In 1980, the average age at which people in Scotland first got married was 24.5 for men and 22.6 for women. By 2000 these figures were 30.5 and 28.6 respectively; in 2016 they were 33.9 and 32.2.

And less people are getting married now, in total; in 1980 there were 38,500 marriages in Scotland. By 2000 it was 30,367, and in 2016 it was 29,229.

When millennials do get married, its less likely to be in a church; Generation Y is also less religious than those which came before it.

Almost two-thirds of 16- to 34-year-olds in Scotland say they have no religion at all, far higher than proportion of those older; less than a third of those over 65 gave this answer.

These broad trends are instructive in their own way, but at the end of the day everyone has their own unique experience. BBC Scotland will be covering the lives of Generation Y in Scotland all this week.

Send in your comments and questions via social media using #BBCGenY or to [email protected].