The myths of Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites

Most people have heard of Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites but their story is often only vaguely known or misunderstood.

The 1745 Jacobite Rebellion was a turning point in British history.

Charles Edward Stuart believed the British throne was his birthright and planned to invade with his Jacobite followers and remove the Hanoverian "usurper" George II.

A new exhibition on the Jacobites at the National Museum of Scotland is the largest in more than 70 years, with over 300 objects on show combining National Museums Scotland's collection with material on loan from around the UK and Europe.

Exhibition curator David Forsyth reveals some of the hidden depths to one of the most tumultuous periods in Scotland's history.

Bonnie Prince Charlie - a mythical figure?

Royal Collection Trust

Royal Collection TrustThe above classic "shortbread tin" image depicts Bonnie Prince Charlie as a highland hero, sweeping into the ballroom at the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh.

In fact the painting, by John Pettie, dates from 100 years after Charles Edward Stuart died and was inspired by an episode from Sir Walter Scott's historical novel Waverley.

Charles did hold court at Holyrood for about six weeks in 1745 but expressly forbade his supporters from excessive celebration of the victory at Prestonpans.

His court was said to be business-like as Charles and his advisors planned the next steps in the campaign, eventually taking the decision to march south for London.

A Scottish hero?

THE ROYAL COLLECTION

THE ROYAL COLLECTIONCharles Edward Louis John Casimir Sylvester Maria Stuart was born in Rome in 1720, about 32 years after his grandfather - James VII and II - the last Roman Catholic monarch of Scotland, England and Ireland - had been deposed from the throne.

Many years later Charles would also die in Rome.

During his life he spent just 14 months on British soil, in 1745-6, and a brief clandestine return visit in 1750.

Charles was raised as a king-in-waiting, successor to his father, James, who was the deposed king's son.

He was installed by his father with the chivalric orders of both Scotland and England, depicted in the painting above - the Order of the Thistle and the Order of the Garter.

James, who still believed himself to be the king, appointed Charles as his Prince Regent in 1743, authorised to act for his father in all things.

He was resolved to reclaim the thrones of Scotland, England and Ireland for his father.

A Bonnie Prince?

National Library of Scotland

National Library of ScotlandThe earlier portraits of Bonnie Prince Charlie show the popular perception of a handsome and charming young man.

Contemporary accounts of the prince appear to confirm this.

In later life, these qualities faded.

The above sketch shows the prince as an old man (about 56) and perhaps the overriding sense is one of disappointment.

He lived for another 42 years after the battle of Culloden of 1746 but was never able to muster support for any further attempts to claim the throne.

Charles became increasingly frustrated and in time embittered by lack of support and betrayal, as he saw it, by his own father and his younger brother, Henry Benedict.

With James' blessing and support, Henry joined the Catholic Church.

This was a grievous blow to Charles, who would wish to distance the Stuarts from the Catholic faith in order to generate support in England.

He even converted to Anglicanism during a clandestine visit to London in 1750.

Charles never spoke to his father again.

Who were the Stuarts?

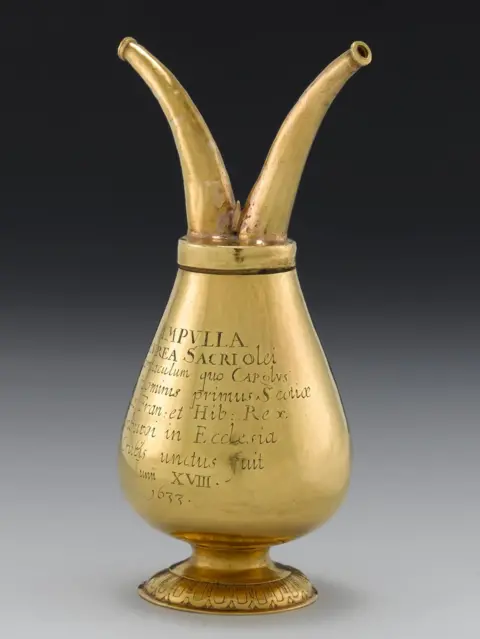

National Museums Scotland

National Museums Scotland The story of the Jacobites is often reduced to Bonnie Prince Charlie and the 1745 rebellion, with limited consideration of what Charles was actually fighting for.

Behind that is the Stuart claim to the three kingdoms.

The Stuart dynasty had ruled Scotland since 1371.

With the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of England at the Union of the Crowns in 1603, the Stuarts expanded their kingdom.

This was still the age of 'divine right' monarchy - the Stuarts believed they were answerable only to God.

The ampulla (pictured above) was a sacred object that held the holy oil to consecrate Charles I during his Scottish Coronation in 1633.

Charles, a firm believer in divine right monarchy, was executed at the end of the English Civil War.

The Stuart line was restored with Charles II, who ruled until his death in 1685.

Why were the Stuarts deposed in the first place?

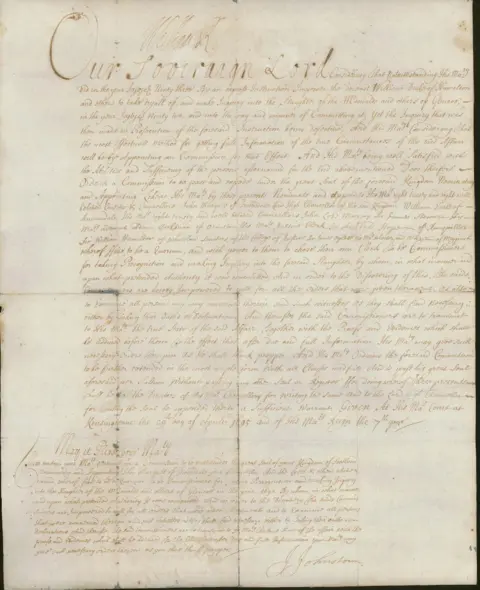

National Museums Scotland

National Museums ScotlandCharles II was succeeded by his younger brother, James VII of Scotland and II of England.

James had secretly converted to Catholicism, as the revelation of his faith would jar with an increasingly Protestant Britain.

The Holyrood Altar Plate (above) is a set of devotional items James used in Edinburgh.

The birth of a male heir raised the prospect of a continuing Catholic succession.

His Protestant daughter Mary was no longer his heir.

A Dutch force led by Mary's husband, William of Orange, was invited to England to restore Mary to her rightful place.

The '45 was actually the last of five Jacobite challenges going back to 1689

NAtional Museuems Scotland

NAtional Museuems ScotlandThe so-called Glorious Revolution, which installed William and Mary on the throne, resulted in James's flight to exile in France.

James then tried to reclaim his throne, with what was effectively the first Jacobite rising in 1689.

It led to violence in Ireland, where James' (largely Catholic) supporters were finally beaten at the Battle of the Boyne and in Scotland where, despite a victory at Killiecrankie, military conflict proved inconclusive.

The Scottish Parliament agreed to adopt William as their king in favour of James.

The Highlands, where the clan chiefs' old oaths were to the Scottish Stuart line, had been the focal point of rising in Scotland.

So the chiefs were ordered to swear fealty to their new king, William.

All did this bar the MacDonalds, who missed an arbitrary deadline.

Many were killed by a government force billeted with them, an act which appalled many and increased Jacobite support.

The Glencoe Massacre of 1692 is one of the most notorious episodes in Scottish history and the outcry over it alarmed King William.

The above document is a warrant for an inquiry into the massacre, signed by King William III.

The commission of inquiry, perhaps unsurprisingly, found there was nothing in the king's instructions to warrant the slaughter.

This is an international story

Royal Collection Trust

Royal Collection Trust After being deposed in 1688, James VII and II went into exile for the rest of his days, along with his family, including the infant prince, James Francis Stuart.

He was welcomed as a guest of his cousin, King Louis XIV at Saint Germain-en-Laye, which the French king had vacated to move into Versailles.

From there, the Stuarts established a court in exile, receiving visitors, conducting international relations and dispensing honours.

When James VII and II died in 1701, Louis recognised his son as James VIII and III, King of Scotland, England and Ireland.

This was not a title King William acknowledged.

Further challenges to the British throne were mounted in 1708, 1715 and 1719.

After the failure of the 1715 rising, the death of Louis XIV and the Treaty of Utrecht between Britain and France, James was obliged to leave France, settling in Rome in 1719.

Charles Edward Stuart was born there the following year.

Was this a war between Scotland and England?

National Museums Scotland

National Museums ScotlandThe Jacobites, named after the latin for James - Jacobus - are often personified as a Scottish movement.

The truth is rather more complex.

The suit pictured above belonged to Sir John Hynde Cotton, a leading Jacobite Tory MP from Cambridgeshire.

He acquired or was gifted this on a visit to Edinburgh about 1743.

There was Jacobite support and sympathy in England although, to Charles Stuart's chagrin, that did not translate into significant military or overt political support in the 1745 rebellion.

In addition, promised military aid from France and Sweden failed to materialise.

Nevertheless, the Jacobite army that took the field at Culloden near Inverness - the decisive battle of the '45 - was not solely Highland. It also had Irish and French units.

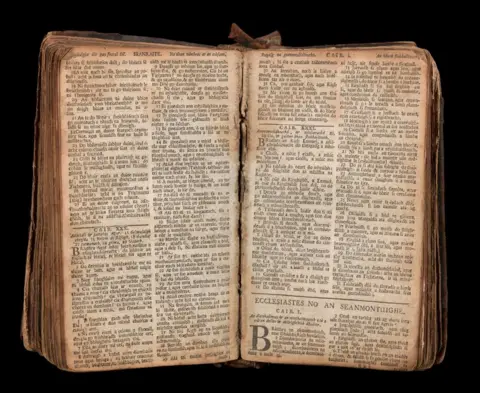

So a Scottish civil war between highlanders and lowlanders?

National Museums Scotland

National Museums Scotland There was considerable opposition to the Jacobites within Scotland.

Bonnie Prince Charlie held court at Holyrood Palace for six weeks in 1745 but, just the length of the Royal Mile away, Edinburgh Castle remained a fortified government garrison throughout.

Glasgow remained loyal to the Hanoverians, who were by now on the thrones of Scotland and England.

This division is sometimes simplified to Highlanders and Lowlanders but there was strong Jacobite support in Aberdeen, Perth and Fife, and indeed some Highlanders fought on the government side.

The Gaelic bible pictured above belonged to a soldier who served with the Argyll militia, raised by the Clan Campbell to fight on the side of the government forces.

It was also not a matter of Protestant v Catholic in Scotland - many of Charles' most prominent Scottish supporters were actually Episcopalian.

Who defeated Charlie?

National Museums Scotland

National Museums ScotlandThe Duke of Cumberland, who commanded the Hanoverian army at Culloden, was the third son of King George.

He is vilified in the popular historical memory for the brutal crackdowns across the Highlands after Culloden, when the traditional right to bear arms and the wearing of tartan and were suppressed as the British government resolved to wipe out the social, cultural and military infrastructure of clan society, which was perceived as a source of loyalty to the Stuarts.

Some Lowlanders welcomed the Duke, and he was granted the freedom of both Glasgow and Edinburgh.

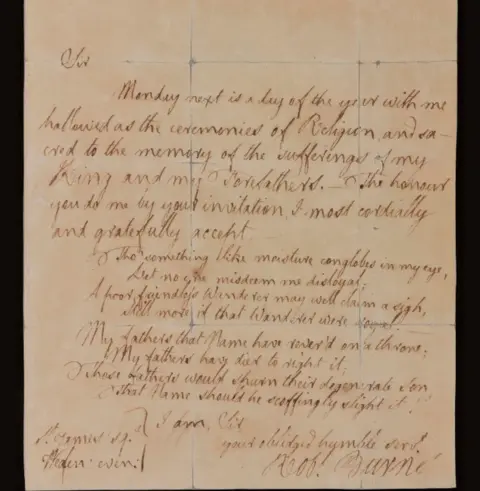

How was Charles remembered?

National Museums Scotland

National Museums ScotlandThis is a letter from Robert Burns, accepting an invitation to attend a "Steuart Society dinner" on Hogmanay 1787, on what turned out to be Charles Edward Stuart's last birthday.

By now, Jacobitism was no longer a threat to the House of Hanover, more almost a gentleman's club, still toasting the kings-over-the-water but, politically and militarily spent.

By this time, after the brutality of the post-Culloden years, efforts were being made to assimilate or rehabilitate (depending on your point of view) the reputation of the Highlander into the emergent British imperial identity, with the revoking of the ban on tartan and the incorporation of the Highland regiments into the British Army.

Charles died in 1788, and was almost instantaneously the subject of this romantic memorial tradition in English - it already existed in Gaelic - which grew with Burns, Scott and others.

Was Charles the last Jacobite 'king'?

Royal Collection Trust

Royal Collection Trust James, the Old Pretender, was buried with full state honours in St Peter's Basilica in Rome in 1766, the only king accorded this honour.

Charles died in 1788, leaving his younger brother, Henry, Cardinal York as the last male heir in the Stuart succession.

Despite being in no position to prosecute the claim, he never renounced it and commissioned rather regal objects like the above Caddinet - a type of serving dish for bread which was traditionally only used by monarchs.

After Henry's death in 1807, Charles was reinterred and the three now rest together in the crypt of St Peter's Basilica.