Could Dominic Cummings really be forced to appear before committee?

BBC

BBCAppropriately enough for the committee which oversees the gambling industry, they're rolling the dice.

In a terse 18-paragraph report the Commons Digital, Culture Media and Sport Committee has announced it intends to put a motion before the Commons, summoning former Vote Leave head honcho Dominic Cummings to appear before their inquiry into "fake news," which has been pursuing allegations around misuse of data during the 2016 EU referendum.

Mr Cummings has declined to appear before the Committee - and the report publishes his increasingly acrimonious correspondence with the committee's chairman Damian Collins.

The DCMS committee is now escalating, by asking the Commons to issue a summons, so that it is no longer just them, but the whole House asking him to appear.

Mr Collins has written to the Speaker to request that precedence be given to a motion in his name seeking an order of the House.

Because this is a matter of privilege, in other words affecting the rights and immunities of the House, the Speaker can decide to give the matter precedence on the floor of the House.

If the Speaker agrees, the motion will take precedence over the rest of the day's agenda - and given the way the inquiry has turned into a probe into the Leave campaign, that could prove quite an interesting debate.

The move to raise this as an issue of parliamentary privilege is a gamble because if Mr Cummings continues to refuse to appear, the next step is to refer the matter to the Commons Privileges Committee...... and what then?

This becomes a test case for the Commons, indeed Parliament's ability to summon witnesses.

Reuters

ReutersAnd there's the rub. It is not clear that Parliament has effective, human rights compliant powers to compel witnesses.

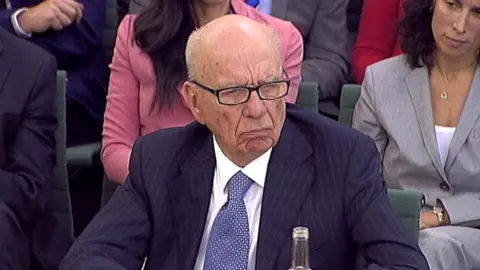

Rupert Murdoch initially declined to give evidence to the Culture Committee in the 2010-15 Parliament, before the eruption of the phone hacking scandal forced him to attend.

Sports Direct boss Mike Ashley ignored repeated requests to be questioned by MPs on the business committee about working conditions at his warehouse - initially calling the committee a "joke" - before finally submitting to a grilling in June 2016.

Irene Rosenfeld, chief executive of the US food giant, Kraft declined to appear before the Business, Innovation and Skills Committee, which criticised her for a "regrettably dismissive attitude" which, in a carefully chosen phrase, "steered close to a contempt of the House".

More recently, Facebook chief Mark Zuckerberg turned down an invitation to appear before the culture committee, a decision Damian Collins called "absolutely astonishing".

The reality was they had no real sanction, beyond public opinion and political opprobrium, to back up their summons.

Mr Murdoch may have, in the end, been persuaded that non-appearance would harm his reputation, when scandal struck his company. And others might fear the reputational cost of refusal.

But any reading of Dominic Cummings' exchanges with Damian Collins suggests that he is not very bothered.

On 10 May, he wrote: "A summons will have ZERO positive impact on my decision and is likely only to mean I withdraw my offer of friendly cooperation, given you will have shown greater interest in grandstanding than truth-seeking, which is one of the curses of the committee system. I hope you reconsider and put truth-seeking first."

Mr Collins said today that he had "made repeated, reasonable requests for him to appear, but so far he has refused to do this".

HOC

HOCThe next step would be to refer the case to the Committee of Privileges which would then hold an inquiry, seeking evidence from the parties, before making a report to the House - which might include a recommendation for further action.

The Commons has the power to admonish those that it finds in contempt, something it last did in September 2016, when the Privileges committee said two witnesses, Colin Myler and Tom Crone, had misled the Culture, Media and Sport Committee by "answering questions falsely".

It recommended that the Commons should "formally admonish" them, and in October 2016, the House debated the motion, including whether the media executives should be summoned to appear at the bar of the House to receive their admonition.

This option was rejected, largely because MPs thought it would look over-theatrical, but they did pass a motion of formal admonishment.

Maybe being admonished for contempt of Parliament might damage Mr Cummings' prospects of returning to Whitehall as a ministerial special advisor, if for example his old patron Michael Gove became PM.

But maybe he would not care.

In their darker imaginings, the Commons authorities fear a situation where the Serjeant at Arms is dispatched to fetch a reluctant witness, only to become embroiled in an embarrassing, and probably televised stand-off.

It is far from clear that the Serjeant has powers to enter private property, still less to put Mr Cummings in an arm lock and frogmarch him to Westminster.

So, if a summons is effectively ignored, what then?

Perhaps MPs would have to legislate to give themselves proper human rights-compliant powers.

There's a handy model available, in the shape of the Australian Parliament's powers - but there is the small detail of finding the time to legislate in the middle of Brexit.