Laura Kuenssberg: Questions politicians can't seem to answer on immigration

EPA

EPAIt's a "betrayal". It's a "slap in the face". The numbers are "shockingly high" and it's simply "unsustainable".

Politicians all seem very cross about the numbers of people from around the world making the UK their home. And they nearly all seem to agree that old chestnut, that "something must be done".

Just wait until they look in the mirror and realise who came up with the new immigration system under which the levels have risen so much (and witness the former prime minister, Boris Johnson, raging in his newspaper column at the folly of the system that he himself introduced).

But the outrage in the last few days, real or not, is no substitute for answers to a set of questions that politicians must confront if they really want change - and many of them are difficult to answer.

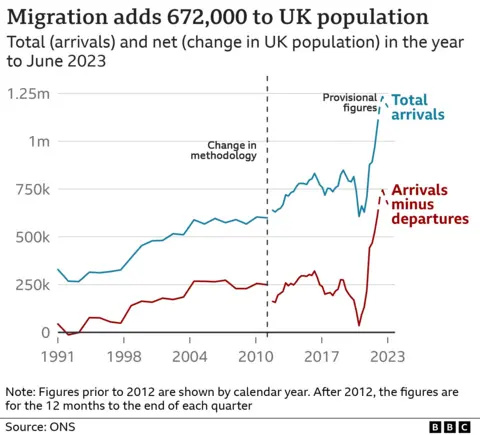

Is immigration too high? With net migration adding the equivalent of the population of Glasgow or Leeds to the country each year, it's not politically fashionable to say that it shows the UK is an attractive destination, and the more the merrier. The stock answer for most politicians is yes, it's too high. We have a broad consensus - so far, so easy.

But this conversation gets tricky, fast. If the level is wrong, what is the right one? The Tories have bad memories of setting a limit and then failing over, and over, and over again to hit it. It was our now Foreign Secretary Lord Cameron who, in 2010 as prime minister, promised to get net immigration under 100,000. Back then it was around a quarter of a million, which seemed sky high, it's more than double that now.

There were plenty of people inside what was then David Cameron's party who argued the vow was crass because we were in the European Union, without the powers to limit the number of EU citizens who moved to the UK. The target was impossible to guarantee. But the political appeal was clear, so he ploughed on - and failed.

Then under Theresa May, there were plenty of Cabinet ministers who believed the promised cap should be junked, even when we were tortuously out of the EU and could manage the numbers ourselves. Her view, however, was that the target should stay - after all, what message would it send if she ditched it? She failed too.

Fast forward to 2023 and the argument for a cap is back, being pushed by the former home secretary, Suella Braverman, among others. But there doesn't seem much appetite to pick a number either inside No 10 or at the top of the Labour Party, who would be giving themselves a potential test that would be hard to pass if they won power.

If they won't say how high, will they say who?

This is where it gets emotive. First, understand the irony: we left the EU on a promise that immigration would get under control because the UK could say exactly who got their passport stamped at our borders. No longer would people from any of 23 European countries be able to arrive and set up home without limit - for good or ill. But since we left, the numbers of people from outside the EU has gone up and up and up.

It's fascinating to crunch those numbers. Nearly a million people from outside the EU came to live in the UK last year (the overall net migration number is lower because that's the difference between those who arrive and those who depart). There were about a quarter of a million Indians, the next biggest group were Nigerian, then Chinese, Pakistani, then Ukrainian, according to the ONS.

The most common reason was to come to study at our universities and colleges (nearly four in 10), but around a third came to work, with a particularly staggering increase in the numbers coming to work in health and social care. The OBR reported this week the numbers of visas granted in that sector had risen 150% in the last year.

No stomach for choosing

If politicians want fewer people to come to the UK, who do they want to say no to? Who would not welcome Ukrainians after the Russian invasion? Who would argue the UK should turn its back on Hong Kongers? Who wants to say that the world's best and brightest students who come to study in the UK should take their talents elsewhere? Who will tell the public the NHS and social care system can't have the staff it needs? Not many people in Westminster have much stomach for picking and choosing.

But this brings us to the fundamental question - if you turn off the immigration taps who will do the jobs that are filled right now by hundreds of thousands of people from all over the world? It is argued that for the government's sums to add up - indeed for the Conservatives to be able to afford the tax cuts they are so eager to offer - the economy needs immigration.

The Migration Advisory Committee, an independent group, was meant to take some of the politics out of this, recommending who could come depending on the gaps in the economy. But trying to take politics out of immigration is like trying to take eggs out of an omelette.

So what decisions could politicians take? The committee itself has already suggested scrapping the list of "shortage occupations" it publishes, which determines the sectors that can bring in extra foreign workers. Labour, and it seems the immigration minister, Robert Jenrick, also wants to end the practice where employers can pay immigrants 20% less than the going rate if their jobs are on the list.

Labour has cited examples such as civil engineers, for whom the official government "going rate" is £34,000 a year, but can instead be recruited from abroad at just £28,000 a year - a tasty incentive for employers to hire from abroad rather than spend the cash training up less experienced staff at home.

Ministers are cutting the number of family members some migrants can bring to the UK when they move. Some Conservatives argue for a cap on the number of social care workers who can come in. Labour argues for a crackdown on exploitation in that industry.

When it comes to the huge numbers of students coming in, some Tories reckon it's time to cut way back, arguing the need to cut immigration should come ahead of the balance sheets of our higher education institutions.

Conservative calls for extra steps are more like screams now. Perhaps the measures they come up with will start to make a difference - but they may seem like nips and tucks in the face of the sheer numbers.

There are plenty of politicians in both parties who'd agree privately that the only way to make a big change in the migration numbers is a massive effort to get the UK workforce into shape.

That is not an overnight fix - for the two decades I have covered politics I have heard politicians talk about the need to skill up the workforce, to improve education and training, to invest in British workers.

Risks are obvious

We heard it in Gordon Brown's ill fated "British jobs for British workers", David Cameron's apprenticeship levy, Theresa May's T-levels, Boris Johnson's Lifetime Skills Guarantee, and Rishi Sunak's planned reforms of the benefits system to get people back into work, the list goes on.

Looking at the numbers of workers firms are bringing in from other countries might lead you to conclude those ambitions didn't get very far.

The political risks from inaction are obvious. Not just because of the ructions in the increasingly restless Conservative Party, but because of what has gone before. Vote Leave insiders identify the day the migration figures were published during the EU referendum campaign as the moment they grabbed the momentum. Boris Johnson, who had previously been reluctant to take a harder line on migration, piled in. You don't need me to tell you what happened next.

- Laura Kuenssberg will speak to Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, Chief Secretary to the Treasury Laura Trott, and Labour's Darren Jones on this week's show

- Watch live on the BBC News website, BBC One and iPlayer from 09:00 GMT on Sunday

The Conservative Party has seen the threat from parties willing to take a brasher line than them - from UKIP and now from Reform UK. Nigel Farage might currently be in the celebrity jungle, but his political arguments have not been banished.

Labour, meanwhile, has learnt painful lessons from failing to take public concern about immigration seriously - just ask Rochdale voter Gillian Duffy about Gordon Brown's infamous "bigoted woman" comment.

The noisy conversation over Channel crossings has been at the forefront of the political imagination for the last year, emblazoned on government lecterns. But that is dwarfed by the numbers of people making the UK their home perfectly legally.

Questions about immigration are not easy for politicians to respond to, and it's daft to suggest they are. But the pressure is on for them to come up with more credible answers. Saying it's too high again and again doesn't make the problem go away. When voters ask the important question of whether they can trust politicians' promises, the answer might be all too clear.

Follow Laura on X

What questions would you like to ask Laura's guests on Sunday?

In some cases your question will be published, displaying your name, age and location as you provide it, unless you state otherwise. Your contact details will never be published. Please ensure you have read our terms & conditions and privacy policy.

Use this form to ask your question:

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or send them via email to [email protected]. Please include your name, age and location with any question you send in.