Report highlights work culture at heart of UK establishment

Shutterstock

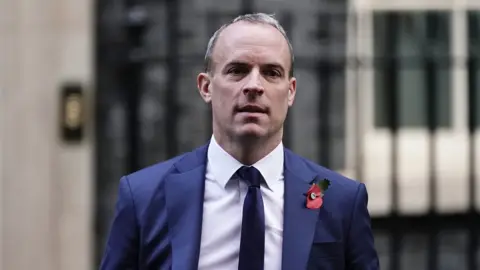

ShutterstockThe report into Dominic Raab's behaviour has shone a light on working practices at Westminster.

The report concluded Mr Raab "abused or misused" his power when foreign secretary and acted in an "intimidating" and "aggressive" way with officials.

Mr Raab resigned ahead of the report's publication.

One of Mr Raab's former advisers said civil servants will be breathing a "sigh of relief". Mr Raab's style as a minister "is one that should be learnt from and ultimately consigned to the history books," he said.

But this result "is not a vindication of the current system" of handling bullying complaints, according Dave Penman, leader of the FDA union which represents senior Whitehall staff.

He said Mr Raab was "not just one bad apple", adding there was a "wider problem with ministerial bullying than the prime minister wants to admit".

Union boss Mr Penman wants to see an independent inquiry into ministerial bullying - something the PM's official spokesman said was not being considered.

He confirmed that Mr Sunak had asked the Cabinet Office to look at how government "can better learn to handle some of the issues that this report has raised, in terms of how concerns about working practices are raised in a timely manner and how they are dealt with".

But the findings in Adam Tolley's report are the latest revelations in a number of accusations of bullying by MPs and cabinet ministers that have surfaced in the past two years.

A survey by the union Unite found 25% of over 650 staff working for MPs had experienced or witnessed bullying. A separate survey by the GMB found 20% of 68 respondents reported having personally experienced behaviour that may constitute bullying at the hands of an MP.

A former senior official Moazzam Malik, who worked with Mr Raab when he was foreign secretary, warned that "the Raab case is not an isolated case" and that "the rules and procedures that govern that conduct and that relationship between ministers and civil servants is under pressure and is not working effectively".

He said civil servants had "lost confidence" in the process for resolving complaints and that "ministers are behaving badly with civil servants."

Mr Malik also said some criticisms of the civil service was also making the relationship between ministers and civil servants more difficult.

He said: "To be described as the blob and to just be disregarded is disempowering, disheartening and actually leads to poor relationships.

"So you know, name calling, lack of trust, inability to get people on side, intimidation, aggressive behaviour, are corrosive for the individuals involved, but actually it leads it undermines our system of government."

There were opposing views about the way Mr Raab worked. A civil servant who worked in his private office, and gave evidence to the inquiry, said they were "very sad" at his resignation, believing he was a good boss.

They said: "The report was not as clear cut as everyone thought it would be" and said it reflected a "big pile-on culture" at the civil service.

Until the report into Mr Raab was published, the most high-profile investigation was into Priti Patel.

The investigation found Ms Patel had broken the ministerial code by bullying staff while home secretary, but she was kept in post by the prime minister at the time, Boris Johnson, who rejected the investigation's conclusions.

Last year, Sir Gavin Williamson resigned as a government minister after he was accused of bullying fellow MPs and telling a civil servant to slit their throat and jump out of a window. He is currently under investigation for bullying by the Independent Complaints and Grievance System (ICGS).

PA Media

PA MediaVictims of alleged harassment at Westminster have told the BBC that they are still too frightened to come forward.

Part of the problem is there is no centralised HR system across parliament, and political staff often fail through the cracks between departments.

There is also no single avenue for bullying complaints. The ICGS was set up to handle all complaints of bullying in Parliament, but the reality is more complex.

The ICGS was established in the wake of the #MeToo movement, to handle allegations of bullying, harassment or sexual misconduct.

Since its founding in 2018 more than 1,241 people contacted the ICGS helpline, but only 207 investigations were launched, according to last year's annual report. It has also been criticised for taking too long to reach conclusions, dissuading people from coming forward.

The process is overseen by the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards, who has no formal powers to sanction MPs. Sanctions are determined by the separate Independent Expert Panel - made up of senior figures from outside Parliament - though the most serious sanctions, including expelling an MP, must be voted on by the House of Commons.

In total the ICGS has found 10 MPs have breached the MPs' Code of Conduct on bullying, including former speaker John Bercow, or sexual harassment.

Last year, the former Labour minister Liam Byrne and Conservative MP Daniel Kawczynski were both suspended from the Commons for bullying a staff member on the advice of the commissioner.

Ministerial code

Given their senior position, ministers are usually investigated by the prime minister's independent advisor on ministerial standards. Even junior ministers can often command large teams of several civil servants and special advisors, known in Westminster parlance as SpAds.

In these cases, the prime minister is the ultimate judge of what counts as bullying. The advisor can, though, suggest where they believe the ministerial code has been broken.

All parties in government have promised to tackle bullying, beefing up their internal codes of conduct over the last few years.

Christina Rees, a former shadow Welsh secretary, was stripped of the Labour party whip in October after allegations of bullying her constituency staff. Labour is conducting an independent inquiry.

And when it comes to dealing with MPs' staff, the GMB unions suggests the House of Commons should handle all bullying and harassment allegations as the overall employer. Unite has also given their tentative support to this proposal.

Successive governments have attempted to reform Parliament to stamp out bullying but the current piecemeal system remains unclear making it difficult to effect change.

There is a lack of confidence that making a complaint will lead to any change, and staff say their only solution is often to either transfer away from their workplace or tolerate the situation until the MP is moved.

"The investigation into Dominic Raab has been really useful in highlighting how serious bullying can be," according to Jenny Symmons, a GMB representative and parliamentary researcher.

"There are far too many MPs who just aren't fit to be managers of people," she says, adding that bullying was widespread in Parliament, and there was not enough transparency and oversight.

"When it happens at the top level of government it means the public aren't getting the level of service they need from civil servants or other staff members working for MPs."