Why high UK energy bills were decades in the making

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn a year of soaring electricity bills and fears of blackouts, energy has become the subject of a bitter blame game.

The world is in the grip of a global energy crisis, sharply exacerbated by the war in Ukraine and the strain that has placed on the supply of gas, a major resource.

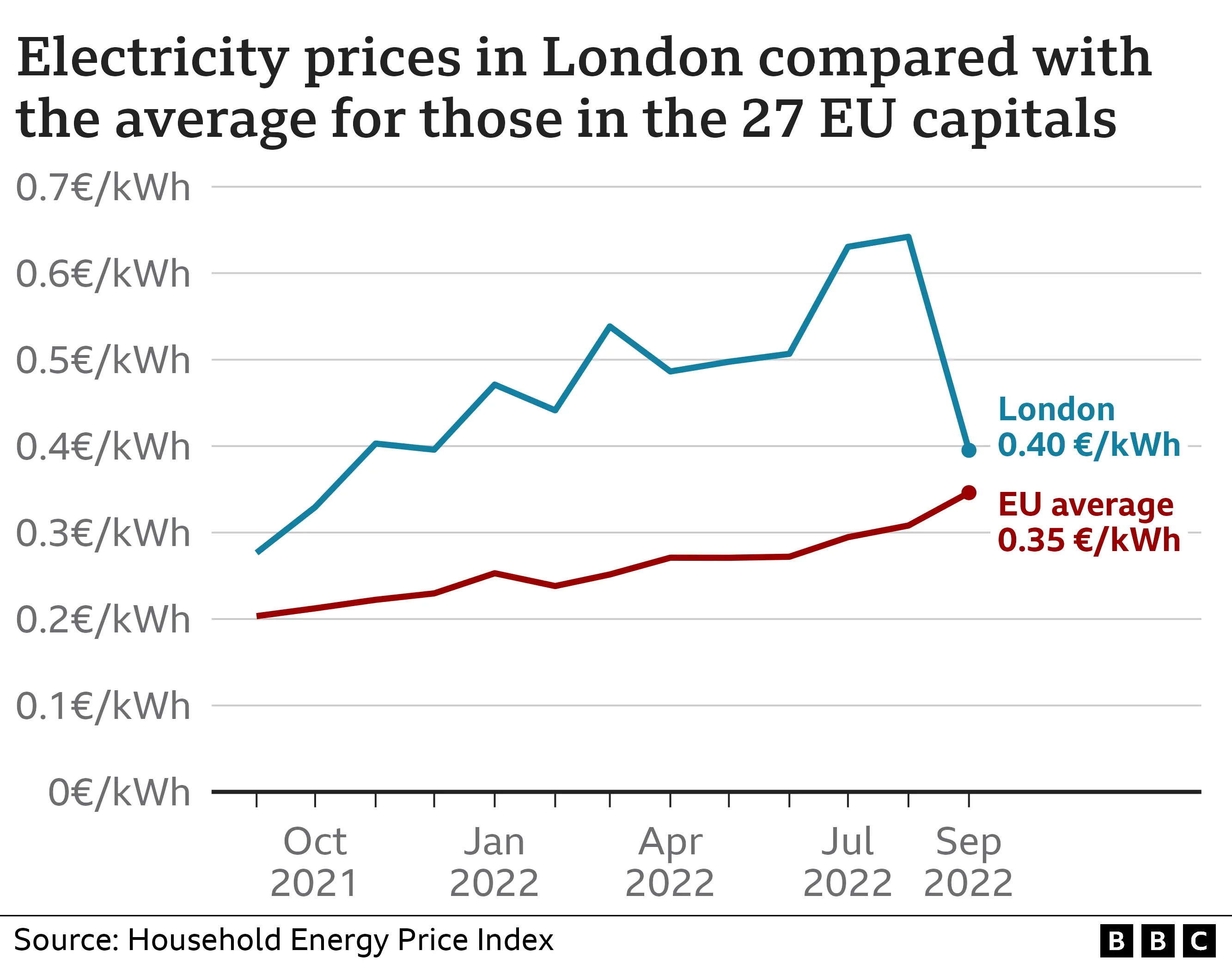

But household energy costs are higher in the UK than almost anywhere else in Europe. How has it come to this?

Looking back at decades of political decisions, former energy ministers and industry experts have told the BBC where they think some mistakes were made.

Gas dependency

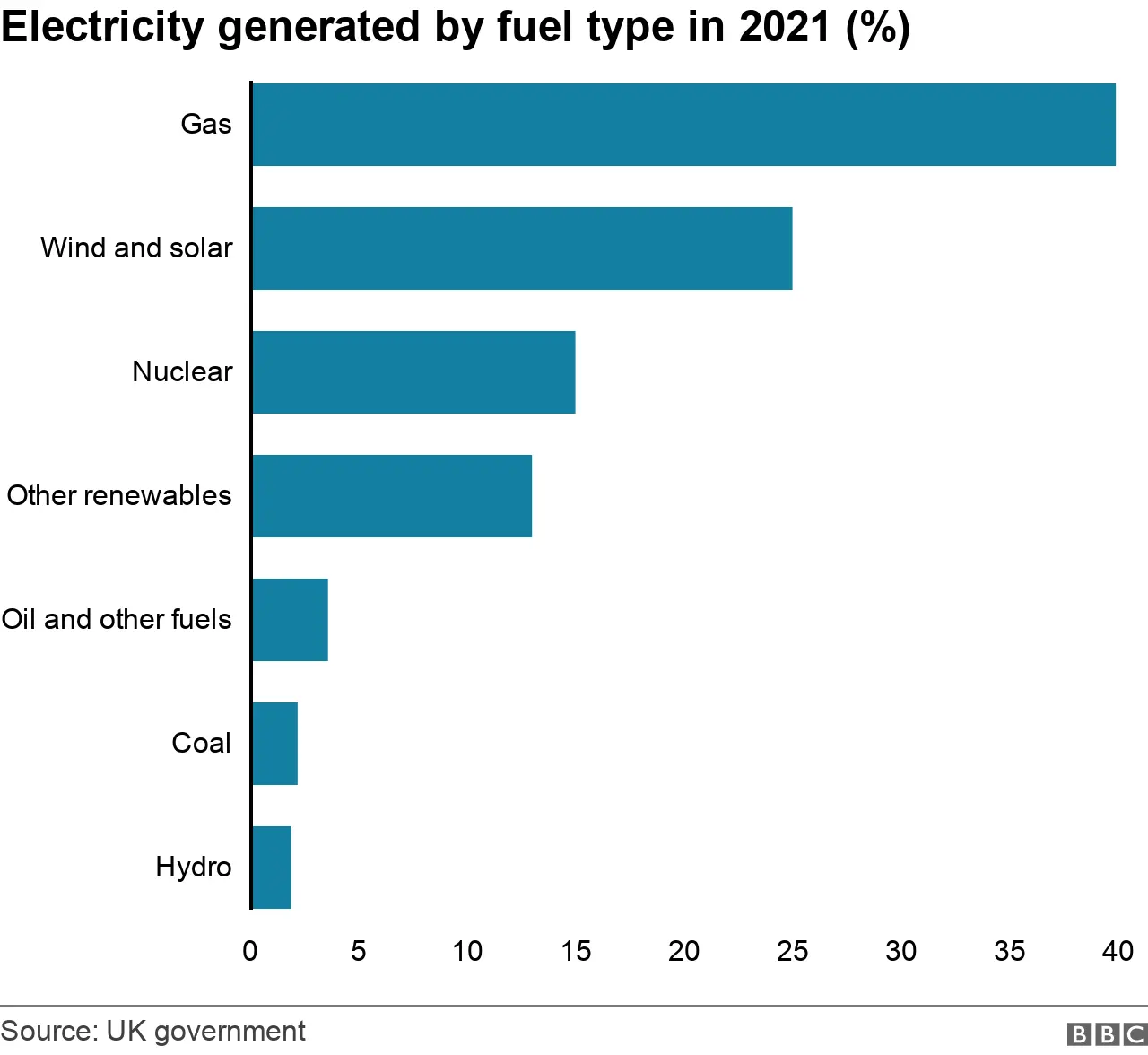

For decades now, UK governments have bet on gas to keep the lights on and our homes warm.

Our appetite grew in the 1990s, when a fossil-fuel frenzy in the North Sea set off what was dubbed the "dash for gas". As that dash slowed to a stroll, the UK became a net importer of gas in 2004 and reliant on supplies from friendly countries such as Norway.

Adam Bell, who was head of government energy strategy until last year, said there was an assumption that global supplies of gas "were always going to be deep".

Mr Bell said the government "wasn't thinking of potential downside scenarios", leaving the UK vulnerable to this year's stratospheric rise in gas prices.

Did anyone see this coming earlier? Brian Wilson, who served as an energy minister in Tony Blair's Labour government from 2001 to 2003, claims he did.

Mr Wilson remembered one sobering forecast that "always stuck in my mind", a projection of almost total reliance on gas imports from Russia. Though it never came to pass, becoming heavily dependent on gas "was something I didn't think was a great idea", he said.

The energy regulator, Ofgem, didn't think so either. In 2009, Ofgem produced an unsettling report, which flagged dependency on gas imports as a key risk to energy security.

The founder of Stag Energy, George Grant, had one idea to mitigate this risk. It involved drilling into salt caves beneath the East Irish Sea Basin to build gas storage for a rainy day.

Ministers were initially enthusiastic about the Gateway Project and planning permission was granted in 2008. Then the financial crisis hit, choking off investment.

While Mr Grant kept making the case for Gateway, David Cameron's government felt "there was not a need to intervene to support more gas storage".

Without state support, his project was sunk. Then the government went even further, ruling out any public subsidies for gas storage. It meant no state handouts for Rough, the UK's largest gas storage facility, which was unable to afford engineering upgrades and was mothballed in 2017.

The no-subsidy policy was "absolutely" short-sighted, Mr Grant said, particularly because the government has since asked him about the possibility of reviving Gateway and pushed for Rough to reopen.

Had we invested in gas storage sooner, "we would have been much more protected this winter", said Charles Hendry, a former Conservative energy minister.

The choice not to had consequences for the UK's energy security, as it did in the nuclear industry.

Nuclear naysayers

In the 1990s, nuclear power generated about 25% of the UK's electricity. Since then, the industry has been in decline, with almost half of the UK's current nuclear capacity due to be retired by 2025.

Notoriously expensive and complex to build, nuclear projects have been kicked around like radioactive footballs by generations of politicians.

"I will diagnose the problem," former Prime Minister Boris Johnson said, announcing state funding for a new nuclear power station earlier this year. "It's called myopia."

He said the culprits were Labour and the Liberal Democrats, whose former leader Nick Clegg snubbed nuclear in "a famous video" from 2010.

Twelve years on, some would argue that the UK could do with a new nuclear plant or two.

The Liberal Democrats had long been opposed to atomic energy, until 2010 when they entered a coalition government with the Conservatives and agreed new nuclear projects could go ahead, providing they took no public money.

Chris Huhne was energy secretary during the first two years of the coalition government. At that point, he said, the industry "was saying we don't need public subsidy".

"We did everything at the time that the nuclear industry was asking for," Mr Huhne said.

That included the introduction of contracts-for-difference (CfD), a price guarantee for nuclear and other generators of low-carbon power. Even then, the industry failed to attract enough investment and several nuclear projects fell through.

The lack of public subsidy "made it very difficult to secure new nuclear plants", said Mr Hendry, who also served in the coalition government. The turn away from nuclear following the Fukushima disaster of 2011 can't have helped either, nor decisions made by previous governments.

Like the Liberal Democrats, Labour was sceptical about nuclear power in opposition before U-turning in office.

Still, some Labour voices in government "were rabidly anti-nuclear", said Mr Wilson, the party's former energy minister. No nuclear proposals were made until 2005, when then-Prime Minister Tony Blair declared the "facts have changed".

"He took his time about it," said Mr Wilson.

The buck doesn't just stop with Labour though. The privatisation of the energy market - started by Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s - has also been blamed for stalling nuclear power.

In 1996, eight nuclear plants were privatised as British Energy by John Major's government. Faced with big start-up costs and uncertain profits, the private sector on its own has not completed any new nuclear power stations since.

This "big structural choice" partly explains "why power prices in particular are so expensive today", said Adam Bell, who is now head of policy at management consultancy Stonehaven.

'Cut the green crap'

Another explanation with more weight, he said, hinges on choices made by Mr Cameron's government.

"The first and most important one was 'getting rid of the green crap'," he said.

The crude phrase, splashed on the front page of the Sun newspaper, was the "PM's solution to soaring energy prices" in 2013. Back then, Labour was campaigning hard on the cost of living, promising to cap energy bills if the party won the 2015 general election.

In a surprise reshuffle, Mr Hendry was replaced as energy minister by John Hayes, who vowed to put "coal back into the coalition".

"He wanted to see a huge growth in coal," Mr Hendry said. "He did really throw the low-carbon agenda into reverse."

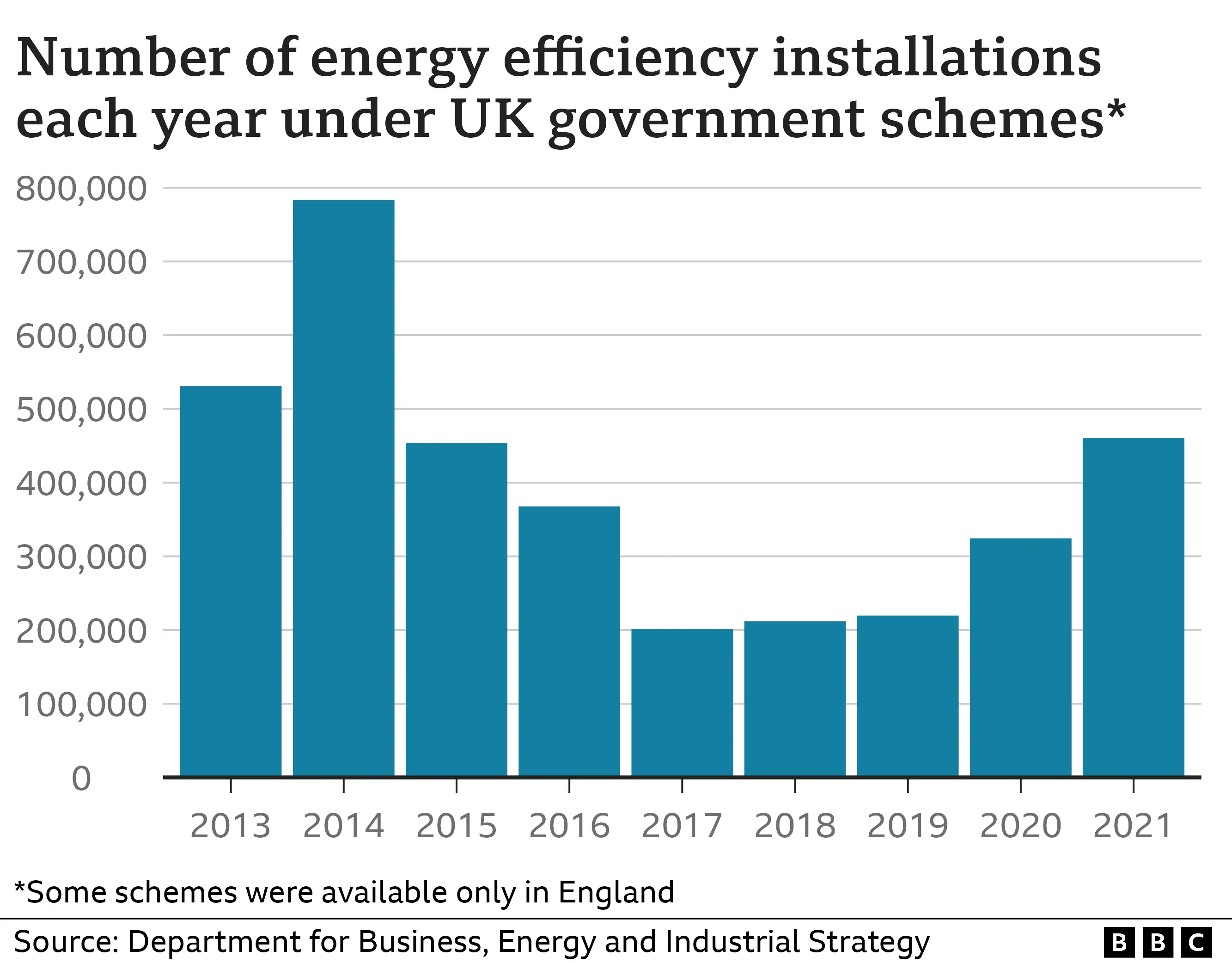

Over the next two years, subsidies for renewables were cut, planning rules for onshore wind were tightened, and a zero-carbon homes policy was scrapped.

Had those green policies remained, estimated annual energy bills would have been £9.5bn lower under the October price cap, according to research by energy analysts Carbon Brief.

The culling of the green deal for home insulation was particularly disappointing for Mr Huhne, who sees the policy as one of his key legacies.

For too long, politicians "haven't wanted to do the boring stuff", said Emma Pinchbeck, chief executive of Energy UK, a trade association.

Instead, they've focused on the "big infrastructure projects, which are sexy", she said.

"For the last decade in this country, every single year we've been missing out on installing energy efficient measures and clean heating, which would have reduced our exposure to these prices.

"And those decisions were made because of pretty short-term politics."

Correction 31 January 2023: A graphic showing the amount of gas in storage in a selected number of countries was removed. The data was sourced to Gas Infrastructure Europe, which does not report the full picture for the UK post Brexit.