New prime minister: Seven big questions for Liz Truss

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLiz Truss, the UK's next prime minister, will arrive in Downing Street to an overflowing in-tray of potential problems - an all-consuming cost of living crisis, dire warnings about the state of the NHS, and an ongoing war in Ukraine.

Seven BBC correspondents identified some of the biggest questions No 10's latest occupant will have to tackle.

Faisal Islam, economics editor

The new prime minister won't actually be able to solve fully their biggest challenge - the cost-of-living crisis. And it's got notably worse during the leadership campaign. At its core is the problem that energy, especially gas, is not flowing normally. This is primarily because of the Ukraine conflict and the conscious actions of the Kremlin. Prices spiked further recently, as European nations stored up gas for the winter.

The overall result is energy prices most people will find unaffordable. The extent, timing, and targeting of help - which will stretch into tens of billions of pounds just for households - are the key judgements the new prime minister will face.

Other prices - especially for food - are also surging, which could lead the inflation rate beyond 15%. All that is before the impact of further falls in the value of Sterling. Meanwhile, interest rates are on the rise, not just for families, but also for companies and the government itself. It is a toxic economic cocktail, and will require judicious, credible, and timely interventions.

Nick Triggle, health correspondent

Getty Images

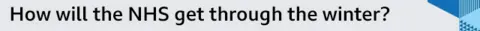

Getty ImagesNHS performance has been deteriorating for the best part of a decade, but the pandemic has exacerbated its problems even further. Record numbers are on hospital waiting lists - nearly one in eight people are currently waiting for treatment. Meanwhile, emergency services are warning patients are being harmed because of delays responding to 999 calls and long waits in A&E.

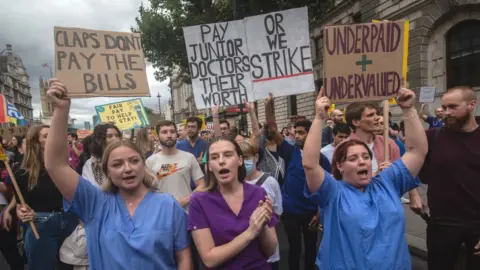

There is the threat of industrial action, with unions unhappy with pay. And all this is happening ahead of winter, with the prospect of flu and Covid circulating at high levels for the first time. Part of the problem hospitals are facing is the inability to discharge patients when they are medically fit to leave because of a lack of social care places.

The government does have a plan for social care - the care cap - but that is about protecting people's assets rather than providing more funding for services. Even then, there has been debate about whether the government is right to increase national insurance to pay for it, in part because of rising inflation.

James Landale, diplomatic correspondent

Boris Johnson offered Ukraine early political and military support. The new prime minister is expected to maintain that approach and is likely to be willing to provide Ukraine with more weapons as the conflict progresses.

But as time goes by, the new prime minister may face a growing challenge of convincing doubters at home and abroad that the economic price of supporting Ukraine is worth it. With rising energy costs exacerbating the cost-of-living crisis, the PM will have to persuade voters that their financial discomfort is needed to defend Ukraine.

There will also be a big job of diplomacy to protect the pro-Ukraine alliance across Europe. There may well be countries that want to seek an accommodation with Russia and end the fighting to help secure their energy supplies.

Ione Wells, political correspondent

After months of infighting, uniting the Conservative party is the main political challenge. And party unity will face an early test: the privileges committee investigation into whether Boris Johnson misled MPs over Downing Street parties.

If the committee of MPs recommends a punishment for Mr Johnson, MPs will need to vote on it. The prime minister will have to decide whether to let Tories vote how they want, or whether to instruct them to vote a certain way. Whipping them to vote for a sanction could anger those who support Boris Johnson, but the opposite approach risks accusations of trying to cover up wrongdoing.

Why does Tory infighting matter when there are pressing concerns, like the cost of living? Firstly, because governments with divided parties can struggle to pass policies that matter to people's lives. Secondly, it can be hard - as Mr Johnson discovered - to land your messages with the public if ministers spend more time on the airwaves trying to defend various behavioural issues, rather than policies.

Jayne McCormack, BBC News NI political correspondent

The next PM will quickly face a conundrum over the Northern Ireland protocol. Talks with the EU all but ground to a halt after the government introduced a bill to give UK ministers powers to override parts of the post-Brexit trading arrangements.

The Democratic Unionist Party declared it won't form a power-sharing government at Stormont until the protocol is changed, arguing it damages Northern Ireland's position within the UK. The key date is 28 October, the deadline for restoring government at Stormont.

After that date, the government will either have to call a fresh assembly election, draw up legislation for a new deadline, or begin taking more decisions for Northern Ireland from Westminster. The PM will also have to bear in mind that most Northern Irish politicians want the protocol to remain and won't shy from laying blame at the door of Downing Street.

Glenn Campbell, BBC Scotland News political editor

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTheresa May made the trip to Scotland on her first full day in office. Boris Johnson arranged his meeting within a week. It's not clear whether the new prime minister will be in quite the same hurry to go at a time when Nicola Sturgeon is pressing for an agreement to hold another independence referendum, in 2023.

In October, the UK Supreme Court will be asked to consider whether or not Holyrood has the power to hold IndyRef2 without Westminster's consent. The weight of legal opinion suggests the answer may be no but if the case goes the other way, the PM would face a big call: allow the vote to go ahead or take active steps to stop it.

In resisting Scottish independence, any prime minister must be careful not to choose an approach that risks undermining support for the union further.

Jonah Fisher, BBC environment correspondent

In the midst of a gas price crisis, the new prime minister will very rapidly have to make decisions on energy that could set us on course to make, or break, the UK's commitment to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Will they prioritise the push for more renewables against the demands from some that they look again at the fossil fuels that already warm our planet? Should new oil and gas projects be greenlighted in the North Sea? Will the new leader give any encouragement to the UK fracking industry?

As part of the net zero strategy, the government has committed to decarbonise the generation of electricity by 2035. For that to happen there will need to be a massive expansion in renewable energy. Offshore wind is already a British success story, but the fastest renewable projects from conception to completion are on land - solar and onshore wind.

Both are currently stymied by the planning process. Could that be simplified to speed up the transition to renewables? Early indications are that the answer will be no.