Private Members Bill ballot: The draw that can make new law

UK Parliament/Jessica Taylor

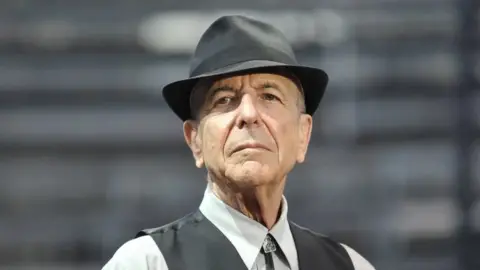

UK Parliament/Jessica Taylor"Everybody knows the dice are loaded, everybody rolls with their fingers crossed…"

I somehow doubt that Leonard Cohen had the Commons Private Members Bill process in mind, when he wrote those lines, but they do amount to an accurate description of the maddeningly obscure system under which a handful of MPs get a chance to bring in the law of their choice.

So those considering doing something controversial like bringing in assisted dying or banning "fire and re-hire" employment practices should keep them in mind.

The basic rule is that it's very hard to force through any measure without a broad cross party consensus behind it, and the government has any number of ways in which it can kill bills it disapproves of.

This week saw the drawing of the Commons annual Private Members Bill ballot, which saw 20 names selected at random.

What they win is varying degrees of priority for debate in the seven Friday sittings which will be set aside to debate whatever legislation they choose. Any MP can introduce a Bill (that is, a draft law) on any subject at any time; the difficult bit is getting time on the floor of the Commons for it to be debated and voted on.

So the MP topping the list - in this instance the SNP's Stuart C MacDonald - will have his pick of the available days to debate whatever bill he chooses.

The top seven MPs in the ballot can each take one of the opening slots on one of the available days. Those lower down the list have a trickier choice… they have to guess which of the bills scheduled first on which days will leave enough time for a debate on their bill.

And debating time here is the critical factor.

UK Par

UK ParIn most Commons debates MPs' speeches are time-limited, but not in these debates - which means it is possible for those opposed to a bill to talk and talk until the allotted time runs out, at which point the bill in question is, effectively, dead.

It goes to the back of the queue for further debating time and is never seen again.

The only antidote is if the bill has more than 100 supporters in place to vote for a "closure motion" to end the debate, and that is a tall order, when most MPs are keen to be out and about in their constituencies on a Friday.

Keen practitioners of the niche art of "talking out" a bill include a group of Conservatives who make it their mission to stop private members bills to which they take exception.

Sir Christopher Chope and his allies can talk for hours, while staying within the rules of order, which (as in Radio 4's Just a Minute) forbid deviation, repetition and hesitation. It can be excruciating to listen to, but also highly effective in killing bills.

EPA

EPAThe last set of PMBs saw several significant measures passed - including on recognising British Sign Language, improving disabled access to taxis and on meeting the care needs of people with Down's syndrome.

Through the vagueries of the ballot, the promoter of that last measure, the Conservative ex-cabinet minister Liam Fox has come fifth in this year's ballot, and will doubtless be employing his legislative wiles on another bill in due course.

Another Conservative, Bob Blackman, whose Homelessness Prevention Act, passed in 2017, must rank as one of the most significant PMBs of recent years, not least because it involved some significant government spending, is in at Number Six in this year's list.

And of course previous PMBs have been at the centre of major controversies; they have legalised abortion and homosexuality, attempted to ban hunting with hounds and bring in assisted dying.

The phones of this year's winners will already be ringing off the hook; all manner of interests and pressure groups will be pushing their own legislative proposals - so watch out for bills to end fire and rehire (as pushed last year by Labour MP Barrie Gardiner) or to allow assisted dying, to name but two possibilities.

It will be a while before the winners have to make their choices - they have to formally present their bills on Wednesday 15 June, so they have to notify the Commons authorities of the title of their proposed measure the day before. At which point the action really begins.