Boris Johnson outlines new 1.25% health and social care tax to pay for reforms

A new health and social care tax will be introduced across the UK to pay for reforms to the care sector and NHS funding in England.

Boris Johnson said it would raise £12bn a year, designed to tackle the health backlog caused by the Covid pandemic and to bolster social care.

He accepted the tax broke a manifesto pledge, but said the "global pandemic was in no-one's manifesto".

However, Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer said the plan was a "sticking plaster".

Leaders in social care also warned the money was "nowhere near enough" and would not address current problems.

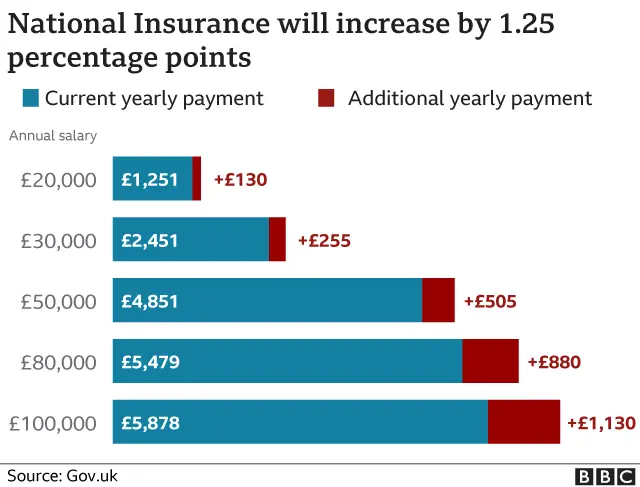

The tax will begin as a 1.25 percentage point rise in National Insurance from April 2022, paid by both employers and workers, and will then become a separate tax on earned income from 2023 - calculated in the same way as National Insurance and appearing on an employee's payslip.

This will be paid by all working adults, including older workers, and the government says it will be "legally ring-fenced" to go only towards health and social care costs.

Income from share dividends - earned by those who own shares in companies - will also see a 1.25% tax rate increase.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies said the latest tax increases amounted to £14bn. Together with those announced in the March Budget, it said, 2022 had seen the highest tax rises in 40 years.

The UK-wide tax will be focused on funding health and social care in England, but Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland will also receive an additional £2.2bn to spend on their services.

The SNP said the tax would "unfairly penalise Scottish families - and leave the poorest in society subsidising the wealthy".

MPs will vote on the new proposals in the Commons on Wednesday.

Mr Johnson said the proceeds from the tax would lead to £12bn a year being raised, with the majority going into catching up on the backlog in the NHS created by Covid - increasing hospital capacity and creating space for nine million more appointments, scans and operations.

A portion of the money - £5.4bn over the next three years - will also go towards changes to the social care system, with more promised after that.

A cap will be introduced on care costs in England from October 2023 of £86,000 over a person's lifetime.

All people with assets worth less than £20,000 will then have their care fully covered by the state, and those who have between £20,000 and £100,000 in assets will see their care costs subsidised.

'Worried sick' about care home costs

June Clay, 92, from Hornchurch, had to go into a nursing home four years ago.

As a property owner, June had to "self-fund", so sold her house to afford fees which over four years have risen to nearly £1,200 a week.

Her capital is almost all gone. The local authority will help, but only up to £640 a week - while the cheapest homes locally charge £900.

Now her children, in their 60s, are considering re-mortgaging their own homes and using their pension savings to pay for her care.

"I made a promise to my mum, that she would stay in that home... I'm worried sick about it," says daughter Sharon.

But she fears the reforms will be "smoke and mirrors" that will not meet the full costs of care.

Mr Johnson insisted that with the new tax, "everyone will contribute according to their means", adding: "You can't fix the Covid backlogs without giving the NHS the money it needs.

"You can't fix the NHS without fixing social care. You can't fix social care without removing the fear of losing everything to pay for social care, and you can't fix health and social care without long-term reform."

But Labour's Sir Keir said the new tax broke the Conservatives' pledge at the last election not to raise National Insurance, income tax or VAT.

He also said the rise would target young people, supermarket workers and nurses, rather than those with the "broadest shoulders" who should pay more.

The Labour leader added: "Read my lips - the Tories can never again claim to be the party of low tax."

The leader of the Liberal Democrats, Sir Ed Davey - who is a carer himself - also said the tax was "unfair", and that the government's plan missed out solutions for staffing shortages, care for working age adults and unpaid family carers.

Mr Johnson said no Conservative government wanted to raise taxes - but he defended the move as "the right, reasonable and fair approach" in light of the pandemic, which saw the government spend upwards of £407bn on support.

Later, during a press conference, the prime minister said he didn't want to raise taxes further but did not promise there would be no further rises before the next election - despite being asked repeatedly to rule it out.

Meanwhile, the government has also announced it will suspend the so-called "triple lock" on pensions for one year following concerns that a big post-pandemic rise in average earnings would have led to pensions increasing by 8%.

Where's the £36bn going?

The government is raising about £12bn a year for three years with these tax rises.

Just over £2bn of that goes to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland under rules on how UK government spending is split.

That leaves £10bn a year for health and social care in England. Most, but not all, of that has been earmarked against particular parts of health and social care.

About £6bn a year has been earmarked for the NHS.

Another nearly £2bn a year will go to social care.

A bit less than half of that will go towards the new funding model (helping people to pay for care) and a bit more than half going on delivering care - training for staff, support for councils and work on making the care and health services work better together.

Some of the remainder will be spent on tax. The Department of Health and Social Care, and the NHS, are big employers and so a tax rise for employers will mean they have to pay more.

But there's still at least a £1bn increase in the DHSC budget that goes into "other", with the government saying they'll announce further details in the coming weeks.

Ahead of the announcement, there was a backlash from number of Tory MPs, who said they were against a rise in National Insurance.

But questioning the PM after his statement in the Commons, many backbenchers instead sought reassurance that the money raised from the new tax would definitely go towards social care.

Former health secretary Jeremy Hunt told BBC Radio 4's World At One that he thought the government had listened to concerns about only making changes to National Insurance, especially as it would "disproportionately target younger people" and not pensioners.

He said: "This new tax is more broadly based and the 10% of pensioners who work will pay it as well."

'Sector in meltdown'

However, there was anger from the social care sector over the amount they had been promised as a result of the tax.

Chief executive of the UK Home Care Association, Dr Jane Townson, said: "This is nowhere near enough. It will not address current issues and some measures may create new risks."

Chairman of the Independent Care Group, Mike Padgham, said it was a "huge opportunity missed for radical, once-in-a-generation reform of the social care system", adding it would not address the staffing crisis which was "sending the sector into meltdown on a daily basis as care providers struggle to cover shifts".

And the general secretary of the Unison union, Christina McAnea, said: "A detailed plan is needed first to mend and future-proof a sector broken by years of neglect.

"Only then will the cost of making good the damage become clear."

The sums are eye-watering, but they've still left health and care bosses disappointed.

The Covid pandemic has had a huge toll on the NHS, requiring an overhaul of how services are run and creating a growing backlog in care.

Even with this money, it will take the health service years to catch up.

Part of the reason for that is that despite the headline figure of £36bn over three years, by the time the money is shared out across the four UK nations and social care takes a chunk, the frontline of the NHS in England is left with little more than half the £10bn a year health bosses were asking for.

Councils are perhaps even more disappointed.

The case for social care predates the pandemic. Governments have been dodging it since the late 1990s so the fact that changes are on the way is being welcomed.

But the cap only solves one part of the problem - protecting people's assets when they face catastrophic costs.

You will still need to be eligible for care to benefit from the cap. Access is rationed so only the most frail qualify - currently half of requests for help are turned down.

Councils say the money will do little to help them tackle this.