The forgotten referendum of 2011

Getty/ PA Media

Getty/ PA MediaThe prime minister is Jeremy Corbyn. The UK is a member of the European Union. Two fanciful propositions, you might think.

And yet there was a moment, a decade ago, where that course could have been set, even if every vote since then had been cast exactly the same way.

It was a moment, therefore, that moulded the politics of the 10 years that followed.

A decade like no other in British politics.

A decade defined by referendums.

We are going to tell you the story of The Forgotten Referendum of 2011: why it mattered in its own right, and, crucially, how it shaped what came next.

What did happen, and what could have happened.

A peacetime coalition

Referendums, those psephological side orders so loved by the Swiss, had long been regarded as rather exotic by the British.

In 2011, there hadn't been a UK-wide one since 1975.

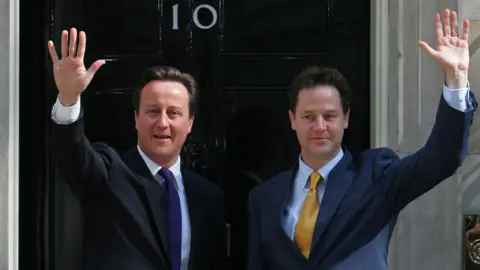

It was the offspring of the politics of the moment; a marriage of convenience between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats.

A coalition, the first in peacetime since the 1930s.

AFP

AFPA political prenup predated its conception; an agreement that we would get a say on the way we collectively choose our government, how our votes translate into who runs the country.

A referendum on the voting system at general elections: whether to keep what is known as First Past The Post, or switch to what is called the Alternative Vote.

I know what you're thinking: this is niche.

But hang on. This is about the most important thing in politics, bar none: power.

Who is given it, who wields it, and how much of it you have at election time.

What is First Past The Post? And what is the Alternative Vote?

Under First Past The Post, voters mark an X next to the person they want to win. The candidate with the most Xs wins.

Under the Alternative Vote, voters rank candidates in order of preference. Only first preference votes are counted initially. Anyone getting more than 50% of these is elected. If that doesn't happen, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated and their second choices allocated to the remaining candidates. This process continues until one candidate has more than 50% of the votes.

So, how do we get from a referendum 10 years ago, with a turnout of 42% and an overwhelming victory for the status quo, retaining First Past the Post, to Jeremy Corbyn in Downing Street? And what about Brexit?

Here is the AV referendum, distilled.

The Lib Dems demand a vote on changing the electoral system, as a condition of going into coalition with the Conservatives.

The Lib Dems aren't much enamoured by AV - because the party has long wanted another system - but they accept having AV as the referendum option as they think it's the best they can get.

The Conservatives hate the idea of First Past the Post being scrapped.

And while officially in favour of AV, Labour are split on it, big time.

There are two campaigns, Yes (to changing) and No (leave things as they are).

Yes starts with a comfortable lead in the opinion polls.

No recruits Matthew Elliott as its campaign director.

He was to go on to be one of the most influential people in politics in the 10 years that followed: he was the chief executive of Vote Leave five years later in the Brexit referendum.

Even then, he tells us, he could see a referendum on the EU was likely, and this would be "good practice".

Yes recruits Katie Ghose as its chairwoman. She had been chief executive of the Electoral Reform Society.

She tells us there was a "fair amount of swagger" on her side in the early days, but "nobody knew what they were doing".

Brexit Central/ Gus Palmer

Brexit Central/ Gus PalmerAs if to illustrate this, Nick Tyrone, the director of finance and operations for Yes, reveals to us, for the first time, that they considered buying big inflatable backsides and putting up around the country, so people could "kick their MP up the behind".

The referendum, after all, came not long after the MPs expenses scandal.

High pressure posteriors never happened, though, because it turns out blow-up bottoms are rather pricey.

And it was, Nick Tyrone reflects, the "worst idea in the history of the universe".

The No campaign, meanwhile, latched on to two insights that would prove crucial: in victory in 2011, and, in the Brexit referendum in 2016.

Firstly, Matthew Elliott tells us it was crucial he gave "Labour voters the permission" to support his cause.

He would do that by courting influential figures from the Labour movement.

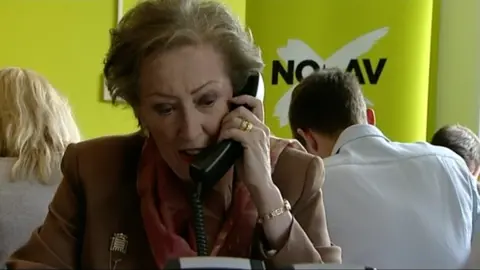

The former Foreign Secretary, Dame Margaret Beckett, was president of No to AV.

Mr Elliott recalls meeting a senior trade unionist.

"He was clearly in favour of keeping the existing electoral system. At the end of our conversation, he said 'well, Matthew. I think you're a BEEP but at least you're going to be our BEEP in this situation.'"

Secondly, he learnt the potency of a big, round, attention-grabbing amount of money, that infuriates your opponents and then linking it to an emotive, tangible alternative to spend it on.

Pretty much everyone remembers the £350m for the NHS on the side of the Vote Leave bus in 2016.

But here is where that idea came from.

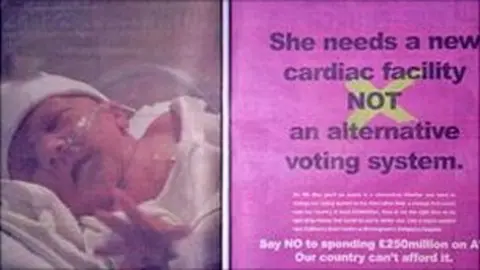

In February 2011, the No to AV campaign published a poster, which read "She needs a new cardiac facility, NOT an alternative voting system."

The she in question: a poorly newborn baby in an incubator.

No to AV

No to AVThe No campaign claimed the Alternative Vote would cost £250m, a figure its opponents said was a "lie."

"They couldn't resist throwing the cost argument back at us again and again. And in doing so, they just kept on repeating the £250m figure again and again and again so voters would hear it. And of course you saw the same thing in the EU referendum," Mr Elliott recalls.

In the end, the result of the AV referendum was decisive: 67.9% of voters endorsed keeping First Past The Post.

Just 32.1% wanted the Alternative Vote.

The politics of 'what if'

Coalition colleagues but AV referendum opponents William, now Lord Hague and Sir Nick Clegg both believe the referendum in 2011 made the EU referendum more likely.

PA Media

PA MediaAll the "bonhomie and goodwill" in the coalition was replaced, Sir Nick says, "with a much, much harder-edged transactional approach" and so the Conservatives got "much less of the things they wanted," which created an "insurrection on the right of the Conservative Party against David Cameron, which then mutated into a heavy push to pull out of the European Union altogether".

Lord Hague reflects that David Cameron, having taken the "calculated gamble" of the AV referendum, thought he could take, and win, "another calculated gamble": the EU referendum.

We all know how that ended.

But what might have happened if the UK had backed the Alternative Vote at general elections?

Politics, like life, is full of what ifs.

There are few, if any, more credible analysts of elections than Sir John Curtice, Professor of Politics at the University of Strathclyde.

So what does he think might have happened in the years since, if we had AV, but people had still voted just as they actually did?

PA Media

PA Media"In 2015, David Cameron would have probably still have had an overall majority, and probably a slightly bigger majority - so we probably would have had an EU Referendum.

"2017, however, probably the Labour Party would have benefited, the Conservatives would have lost out and Theresa May probably would not have had the seats inside the House of Commons to be able to form an administration, even with the support of the DUP."

So Jeremy Corbyn would have become prime minister - and if his government had been stable, he would still be prime minister now.

And perhaps Brexit would have never happened.

Matthew Elliott shares Sir John's analysis.

"It was a forgotten referendum, but had it gone the other way that would have had profound implications.

"With a Jeremy Corbyn and Lib Dem government after 2017, it's fair to say that we wouldn't have Brexit now."

The Alternative Vote "would have changed future election results and we wouldn't have had Brexit", he concludes.

An extraordinary alternative history.

And all springing from the Forgotten Referendum.

Chris Mason presents The Forgotten Referendum, an edition of Archive on 4, at 8pm on Saturday 20th March on BBC Radio 4. Or catch-up whenever you like on BBC Sounds.