Labour: Historic divisions over patriotism pose challenge for Starmer

PA Media/Getty Images

PA Media/Getty ImagesEarly in his tenure as new Labour leader, Sir Keir Starmer said he wanted the party to be "proud of being patriotic".

In his first speech to the party's conference as their leader last September, Sir Keir said to voters: "I ask you: take another look at Labour. We're under new leadership. We love this country as you do."

It seems to be a stance that chimes with many Labour members.

According to a YouGov poll in January 2020, as the leadership contest began, 50% of the party thought it was important for the new chief to have a sense of patriotism.

It resonates among the public too: in a survey, 67% of respondents told YouGov in June 2020 they were proud of being British.

But the party has a complex relationship with the concept of patriotism and Sir Keir will face challenges in getting it right.

Labour historian and author of Old Labour to New, Greg Rosen, says the party tradition is rooted in patriotism, but tensions came with the approach of World War One.

Former Liberal Party members joined Labour, upset by the Liberal stance on foreign policy - and the split between those for and against the war encompassed not just the House of Commons, but the Labour Party as well.

Shami Chakrabarti, the former shadow attorney general under Jeremy Corbyn, says she was surprised by the divisions as she learnt the history of the party.

She points to a story in a new book by Rachel Holmes, Sylvia Pankhurst - Natural Born Rebel, featuring an incident with Keir Hardie - a founder of the party. Keir Hardie was against World War One and spoke out about it in the Commons.

But some Labour backbenchers defied him by quietly singing the national anthem "like a cold, cold wind" from behind, in a stunt to discredit him as anti-patriotic.

"I was shocked, not just that Labour MPs could be so wrong about that tragic imperialist war, but that they were so nasty to their first leader who brought them into being," says Baroness Chakrabarti.

Keir Hardie wasn't alone in his opposition to that war - Mr Rosen points to the resignation of Ramsay MacDonald, who quit as Labour leader in 1914, after saying he believed Britain should have remained neutral.

Yet, at the same time, other leading Labour figures made it onto the frontbench of the coalition government to lead the war effort.

PA Media

PA MediaThis divide on foreign policy - with only those supportive of the war deemed "patriots" - continued.

Mr Rosen said there were "immense tensions" in the 1930s and 1940s within Labour over the rise of fascism and Hitler.

"It saw some figures far firmer in their determination to stand up to fascism than the Conservative Party, while others were quitting over their beliefs in pacifism," he says.

The former shadow chancellor, Ed Balls, says this was a time Labour could point to, when it showed its patriotic background.

"There have been points of tension, but if you think back to the moment of greatest peril in the last 100 years - 1939, when our national identity and national security were the most challenged - that was the moment the Labour Party joined with Churchill in a war time cabinet," he says.

"British patriotism and unity at that time of greatest need was underpinned by Labour but that was consistent with the party pushing for change."

In 1945, despite Churchill's leadership through the war, it was Labour and Clement Attlee that won the post-war election.

"Part of the reason Labour won in 1945 was because it was seen as the party that was both patriotic but also had vision for a better Britain - not just proud but willing to act - to defend and change the country," says Mr Balls.

But Attlee, who is celebrated as the great reformer and founder of the NHS, was also responsible for securing the UK's nuclear deterrent - another topic which divides Labour opinion.

Symbols of patriotism

John Denham - a cabinet minister under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown - said Labour's approach began to change after the "explicitly patriotic" governments of the post-war era.

"From the early 1980s, that question of defence policy was again closely associated with patriotism," he said.

"The party made a pledge in its manifesto for unilateral nuclear disarmament. But the merits of this went up against the patriotic representation of Margaret Thatcher's policies around the Falklands War.

"It put Labour on the back foot for voters who looked for strong military presence from their leaders."

Mr Balls points out: "Every Conservative conference had flown the Union Jack and used as many patriotic symbols as possible, as well as being strong on law and order, and defence.

"Labour hadn't matched that."

But, he says, there was an issue on the left over whether to even try.

Ed Balls says there was a tension between "people who wanted to start international engagement from a place of patriotism, like David Owen, and those like Roy Jenkins, who I think saw internationalism as an alternative to patriotism".

Mr Denham, who also co-founded the English Labour Network, says it was "crucial" to Tony Blair's election win in 1997 that accusations of the party not being patriotic were "neutralised".

And Ed Balls - who won his seat as an MP in 2005 - saw some new and surprising moves by Labour.

He says: "I remember very well in the run up to 1997 election, Peter Mandelson brought a bulldog to a press conference in a Union Jack waistcoat.

"It was part of New Labour signalling that this was now a party that was very proud of Britishness and would do the things that were necessary to protect out national security."

As well as embracing a more overt patriotism in this era, New Labour ushered in another change - this time, in the party's membership.

"Historically, the membership was filled with trade unions and their even bigger base in the manual, industrial working classes," says Mr Denham. "There was a built-in socially democratic, patriotic structure here.

"But the membership became more middle-class, with more graduates and more city-based people. That means it is drawn from that section of society that, in general, is less likely to think about the issue of patriotism."

Twitter

TwitterThis cohort has continued to expand among Labour members in the years after Tony Blair and Gordon Brown.

And in the latest chapter of Labour's history, it has been coupled with growing numbers on the very left of the party.

The party's contortions were epitomised by the incident where Emily Thornberry resigned from Labour's front bench in 2014, after sending a tweet during a by-election which was branded "snobby".

She apologised for the tweet, which showed a terraced house with three England flags, and a white van parked outside.

The Corbyn question mark

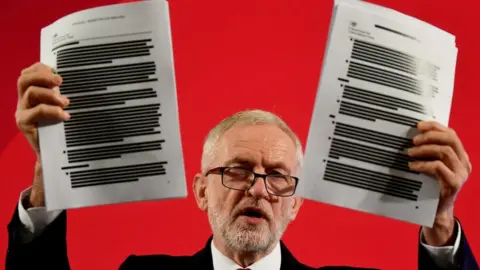

Jeremy Corbyn was a well-established backbench rebel who showed off his left wing stripes when he took over as leader in 2015.

He would speak on the record about his love for the country and support for the Armed Forces but his well-known views on the monarchy, military action and incidents such as criticism from Labour MPs that he opted to remain silent rather than sing the national anthem at a service to mark the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Britain, left a question mark over him for some voters who were looking for a patriot in their next prime minister.

Former Labour MP Jenny Chapman - who lost her seat in the 2019 election and chaired Sir Keir's campaign to become leader - says: "He cleared the pitch. He walked away from the flag, he didn't stand up for the national anthem, he didn't dress appropriately for an important remembrance event.

"People care about these things and it is about respect - respect for them and respect for the country. It may sound very superficial, but it means an awful lot to people, and that is where Jeremy lost permission to have any nuance on this."

Ms Chapman says patriotism was a "real issue" on the doorstep in the 2019 election - which saw her lose her seat as an MP in Darlington.

"They would be very blunt about it," she says. "They would call Jeremy a communist or a terrorist and it isn't fair. I have never been a Jeremy fan, but he isn't those things.

"And they would say he didn't love this country. I am not saying it was true or fair, but that was the perception and it is one we need to correct."

Other issues were, of course, at play, but few dispute that the perception of Mr Corbyn - true or not - damaged the party's performance in those more traditional, working class constituencies, especially in the north of England and the Midlands - the so-called "Red Wall" seats.

Reuters

ReutersIn April, Sir Keir won the Labour leadership contest outright.

For Baroness Chakrabarti, Sir Keir's task is to redefine what patriotism means.

"I personally have no problem calling myself a patriot," she said. "I am a universalist, an internationalist, a human rights activist, but I also understand that people are rooted in place, language, culture and stories."

She is happy to list things that make her feel patriotic, including the English language, the rule of law, and the Commonwealth, but says: "Rather than reducing patriotism to flags and uniforms, we should change the narrative."

Baroness Chakrabarti wants Labour to focus its patriotism on sources of pride - rather than taking on the more traditional, flag-waving patriotism of the right - such as Britain's "greatest national treasure", the NHS.

"Contemporary patriotism should be about loyalty to care and health workers in blue, sent into modern day mines, mills and trenches without adequate testing or protection," she says.

"We should be patriotic about the NHS, not looking for more wars or trying to compete with the right wing populism of Johnson and Trump."

'Patriotic reform'

Ed Balls believes bringing together an internationalist view with the country's national interest is the right balance - and one which has proven fruitful in the past for Labour.

"The 1945 government was a reforming one, but it did so with strong patriotic language about the kind of Britain we wanted to build," he says.

"Labour must use the 1945 election as exemplar of patriotic reform because, if you are not a reformer, why are you in Labour, and if you are not a patriot, you don't take the country with you.

"Those red wall seats, areas I used to represent, want change and are deeply patriotic places that are very proud of that Britishness. Standing up for that combination of change and national pride is vital if Labour is to succeed."

So what is the feeling in Sir Keir's camp?

Jenny Chapman says they have accepted that some voters "sense we see the world in a different way and that we are embarrassed, uncomfortable or feel guilty about being British".

"I have never felt like that, Keir doesn't feel like that and many Labour MPs don't either," she adds. "But it is the reality of what people think and we can't just ignore it."

But how do you appeal to voters who want to celebrate their Britishness without losing the membership less comfortable with the notion?

"You highlight that they have more in common," she says.

"There are things very important to both groups of people - the nature of work, the quality of public services, economic credibility - and Labour needs to make those the most important questions."