Who would win if a general election were held now?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWith the UK about to get a new prime minister, the prospect of an early election is not far-fetched. But should one be held, neither the Conservatives nor Labour could feel confident about winning an overall majority.

The face of party politics in the UK has undergone a dramatic change.

The deadlock over Brexit has been followed by a dramatic decline in support for both the Conservatives and Labour.

As a result, the two parties' traditional dominance of the electoral landscape is facing an unprecedented challenge.

When, on 15 November last year, Theresa May unveiled the deal she'd negotiated with the European Union, that dominance was still in evidence.

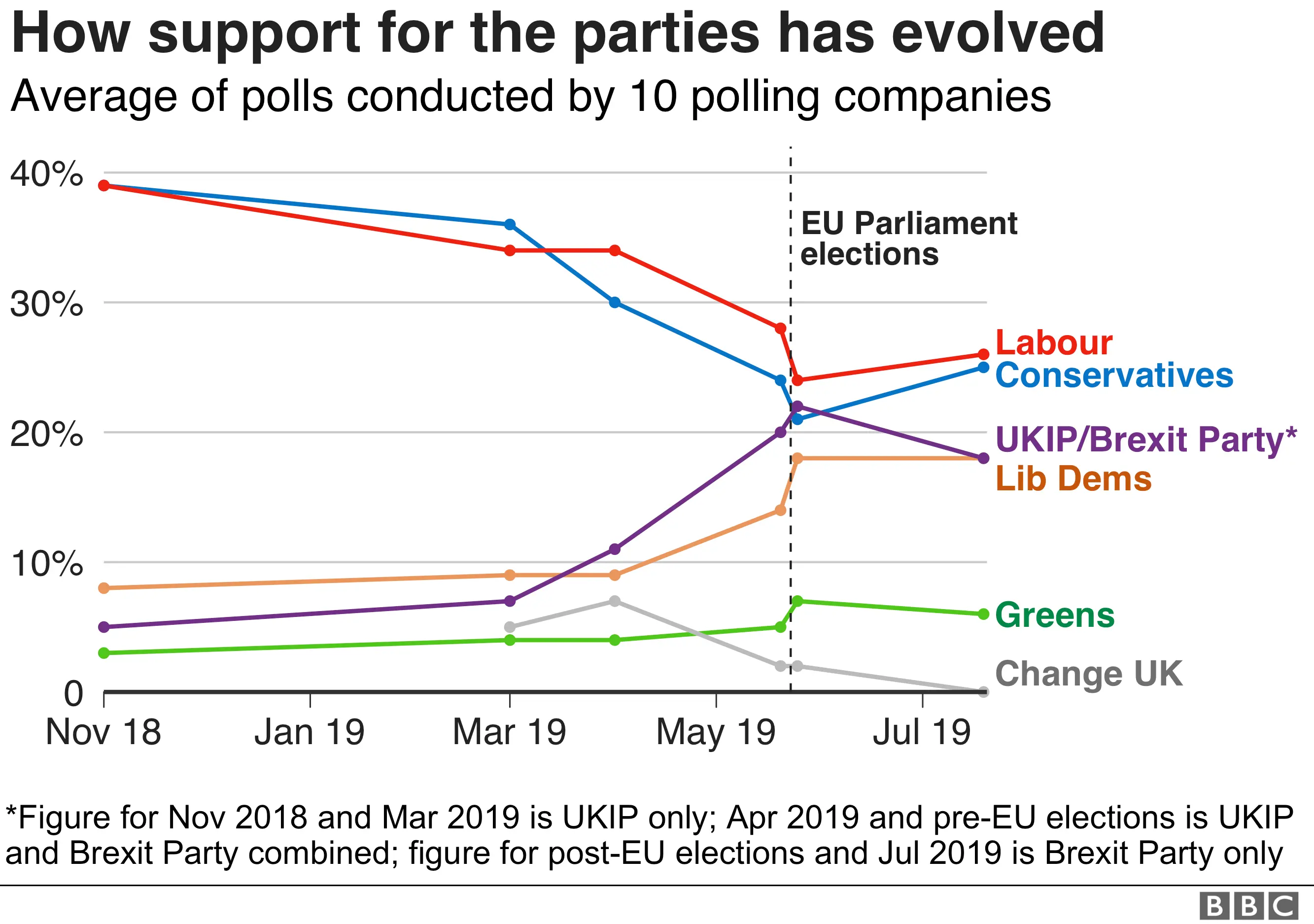

Both parties were averaging 39% in the opinion polls. Their combined tally of 78% was only a little down on the 84% share of the vote they had jointly secured in the 2017 election, the highest proportion since 1970.

Neither the Liberal Democrats nor the Greens were showing much sign of advancing on the 8% and 2% that they respectively won in 2017. At 5%, UKIP's tally was only up by three points on its poor performance at the same election.

Support for the parties now

Nine months later, the picture could not be more different.

True, the Conservatives and Labour are still more or less neck-and-neck - but now they each enjoy the support of just a quarter or so.

UKIP's role as the principal voice of Euroscepticism has been wrested from its grasp by a new party, the Brexit Party. Its current average poll rating of 18% is as high as anything UKIP ever achieved.

The Liberal Democrats also stand on 18%, their strongest position since they entered into coalition with the Conservatives in 2010. Their performance seems to have snuffed out an attempt by a group of Labour and Conservative rebels to form a new "centre" party, Change UK.

The Green Party, too, is enjoying something of a revival; its 6% support puts the party in its strongest position since the 2015 general election.

The only party to have experienced little change in its fortunes is the SNP in Scotland. Five Scottish polls since the beginning of April have put the party on an average of 40% of the vote north of the border. That is just a couple of points above where the party stood in the autumn, and three points above its tally in 2017.

In contrast, both the Conservatives and Labour have seen their Scottish support slip, leaving the SNP well ahead of all of its rivals.

That means that not only are there as many as four parties recording substantial levels of support across Britain as a whole, but also a fifth which has a stranglehold on Westminster voting intentions in Scotland.

When did support shift?

The first signs of a crack in Conservative-Labour dominance were already in evidence when the UK failed to meet the original Brexit deadline of 29 March.

Support for the Conservatives fell on average by three points between mid-November and the end of March. It immediately fell by a further six points as soon as the Brexit deadline was not met.

Support for Labour also eased by five points during this period.

Conversely, support for UKIP and the newly formed Brexit Party was beginning to rise, reaching 11% immediately after the failure to leave the EU in March.

These were clear warning signs that a continuation of the Brexit impasse could well do neither the government - nor the opposition - much good.

However, the pivotal moment was the European Parliament elections that had to be held in May because the UK was still in the EU. That helped put the issue of Brexit at the forefront of voters' minds.

The Brexit Party, which was advocating leaving the EU without a deal, stormed into first place.

PA

PAThe Liberal Democrats, in favour of another referendum, came second.

And although some of their respective supporters would not have voted the same way in a general election, many would have done so.

By polling day, as many as one in five were indicating that they would vote in a general election for the Brexit Party or - in much smaller numbers - for UKIP.

At the same time, support for the Liberal Democrats was now also firmly in the mid-teens.

Both Labour and, especially, the Conservatives were now struggling to retain as much as a quarter of the vote. The battle for Westminster suddenly looked like a four-party rather than a two-party one.

How Brexit remains the big issue

And - so far - that more or less remains the position, even though the European elections, but perhaps not Brexit, are beginning to fade in voters' memories.

Support for the Liberal Democrats remains exactly where it was at the end of May, while the Brexit Party's vote has only slipped a little - by four points.

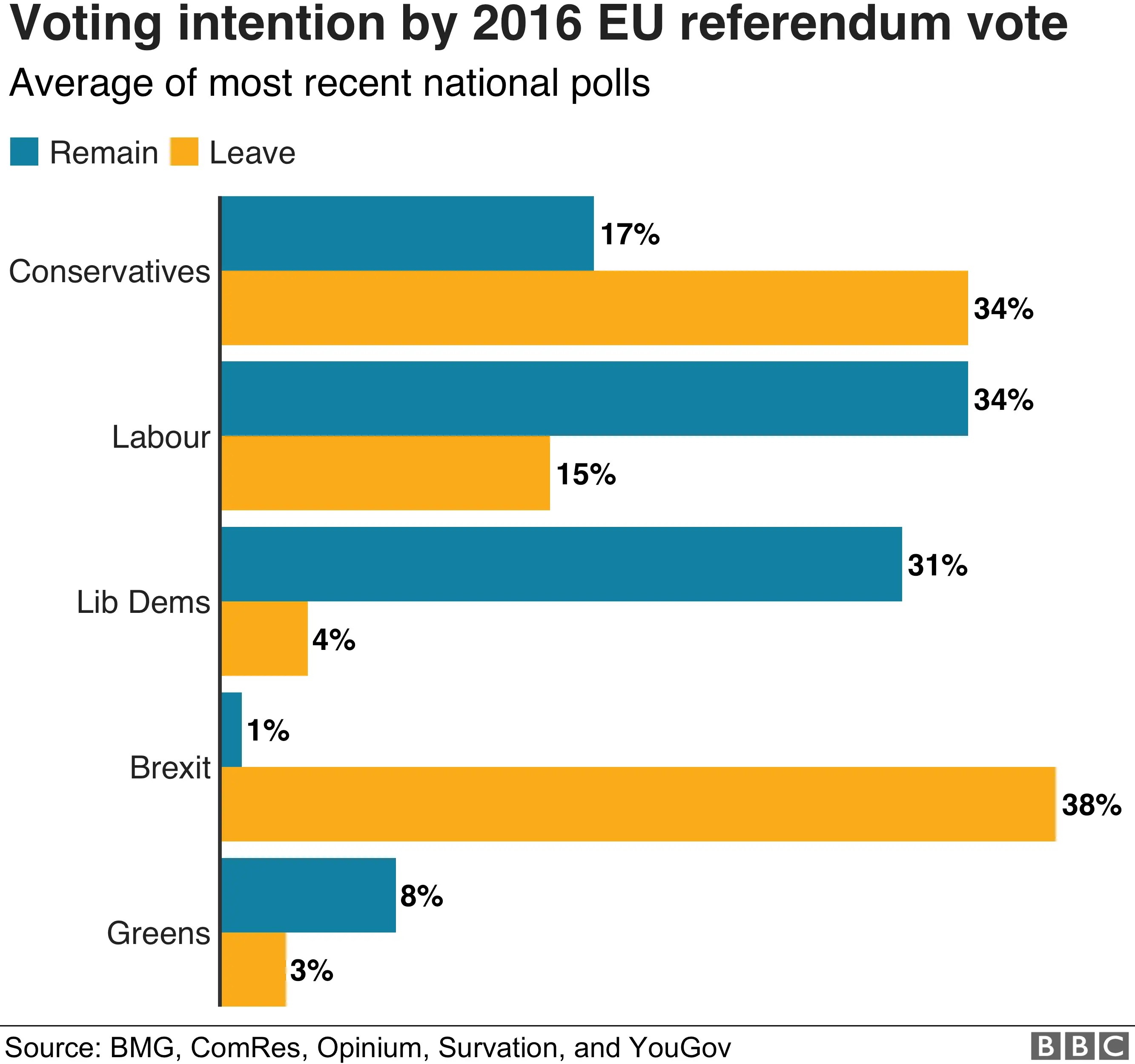

Both parties hold an uncompromising position on Brexit, and their support comes almost exclusively from those on one side or other of the Brexit debate.

Nearly all of the Brexit Party's support is from those who voted Leave, among whom it is the single most popular party.

Support for the Liberal Democrats is predominantly from those who voted Remain, for whose support the party is evidently in close competition with Labour.

The Conservatives are more popular among Leave supporters than their Remain counterparts - and the opposite is true for Labour. But both parties still secure a substantial proportion of their support from a minority who hold the opposing view.

Now that many voters seem to want to use their ballot paper to express their view about Brexit, it is difficult for the Conservatives and Labour to maintain their cross-Brexit support.

Would the new PM want a general election?

The apparent inability of the House of Commons to make any decision about Brexit is a problem for the new prime minister. Some suggest he will eventually find it necessary to hold a general election, to try to change the Parliamentary arithmetic.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHowever, at the moment at least, the advent of four-party politics, or - given the position in Scotland - five-party politics, does not make this an attractive prospect.

Quite how the current numbers in the polls would translate into seats in Parliament is highly uncertain.

Support for both the Liberal Democrats and the Brexit Party could be scattered so evenly across the country that they would end up winning few seats.

But even bearing this possibility in mind, it is still highly unlikely that either the Conservatives or Labour would be able to win an overall majority, or even come close to one.

A new government could find itself in much the same position as the one in which Theresa May has found herself - reliant on minority parties to remain in office and constantly at risk of Parliamentary defeat, including on Brexit.

That said, all eyes will be on what happens to the polls when the new prime minister is installed.

No fewer than one in four of those who voted Conservative in 2017 is currently saying they would vote for the Brexit Party.

Meanwhile, Boris Johnson, at least, is popular with many Brexit Party supporters.

Maybe the Tories will soon be enjoying a lead in the polls thanks to a squeeze on the Brexit Party vote.

That could make an early election a more attractive prospect to them.

But equally, perhaps, the new prime minister will discover that Brexit Party voters are reluctant to return to the Tory fold until Brexit has actually been delivered.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Sir John Curtice is professor of politics at Strathclyde University, senior fellow at NatCen Social Research and The UK in a Changing Europe.

Edited by Duncan Walker

Charts by Mike Hills