European Elections: What they tell us about support for Brexit

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere were two largely separate battles taking place in the European elections in the UK.

The first was for the support of those who voted Leave in the 2016 referendum, many of whom are disappointed that the UK has not yet left the EU.

The second was for the backing of those who voted Remain, many of whom are hoping that the decision to leave the EU might yet be reversed, perhaps via a second referendum.

The outcome of the first battle was decisive and widely anticipated. The second was rather messier, but might have just as important an impact on the debate about Brexit between now and when the UK is due to leave the EU on 31 October.

Leavers vote Brexit Party

Many Leave voters had previously supported UKIP under Nigel Farage's leadership, before backing the Conservatives in the 2017 UK general election.

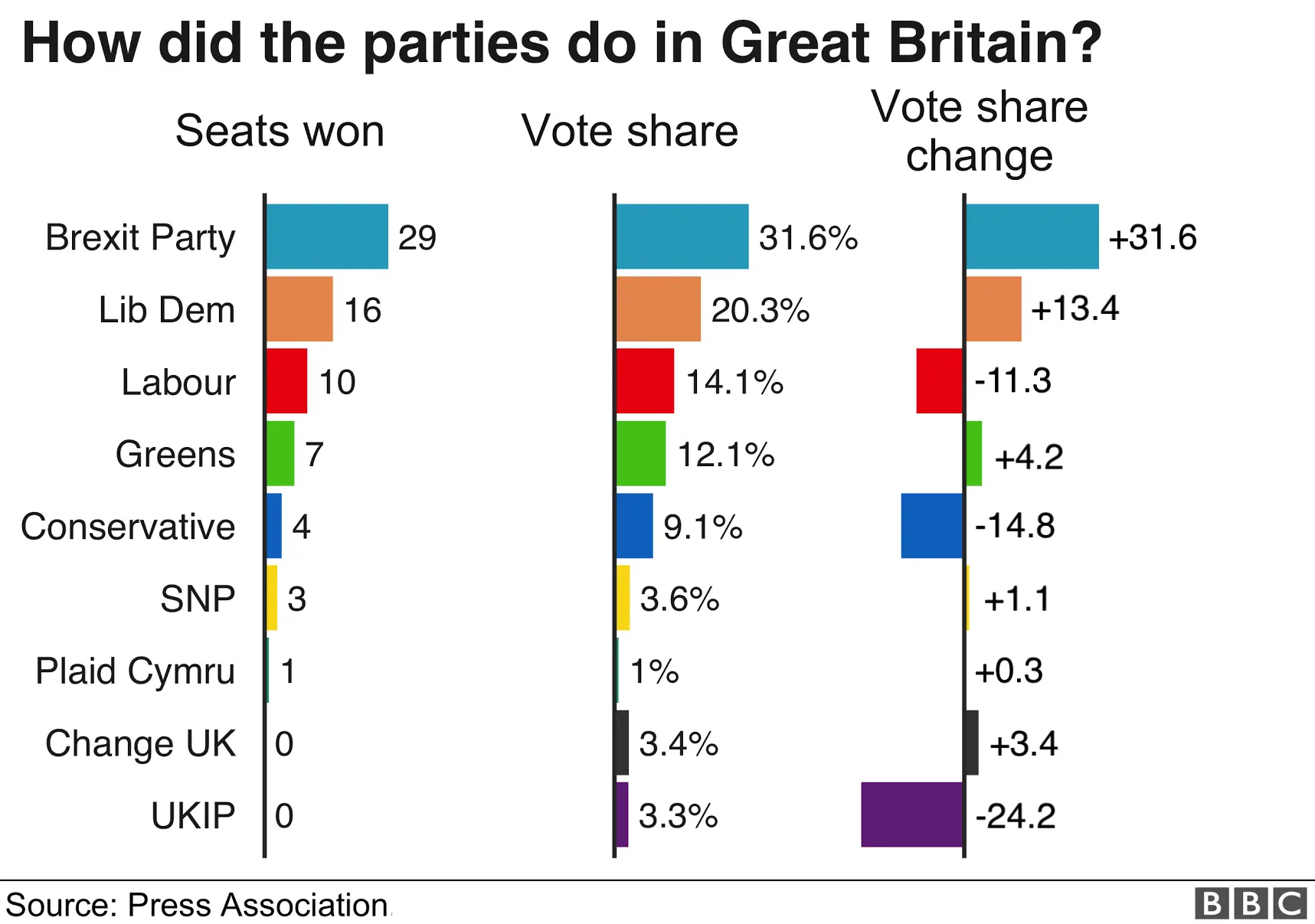

They switched en masse towards Mr Farage's new organisation, the Brexit Party. With 32% of the vote, its level of support was as much as five points higher than that of UKIP in the last European elections, in 2014.

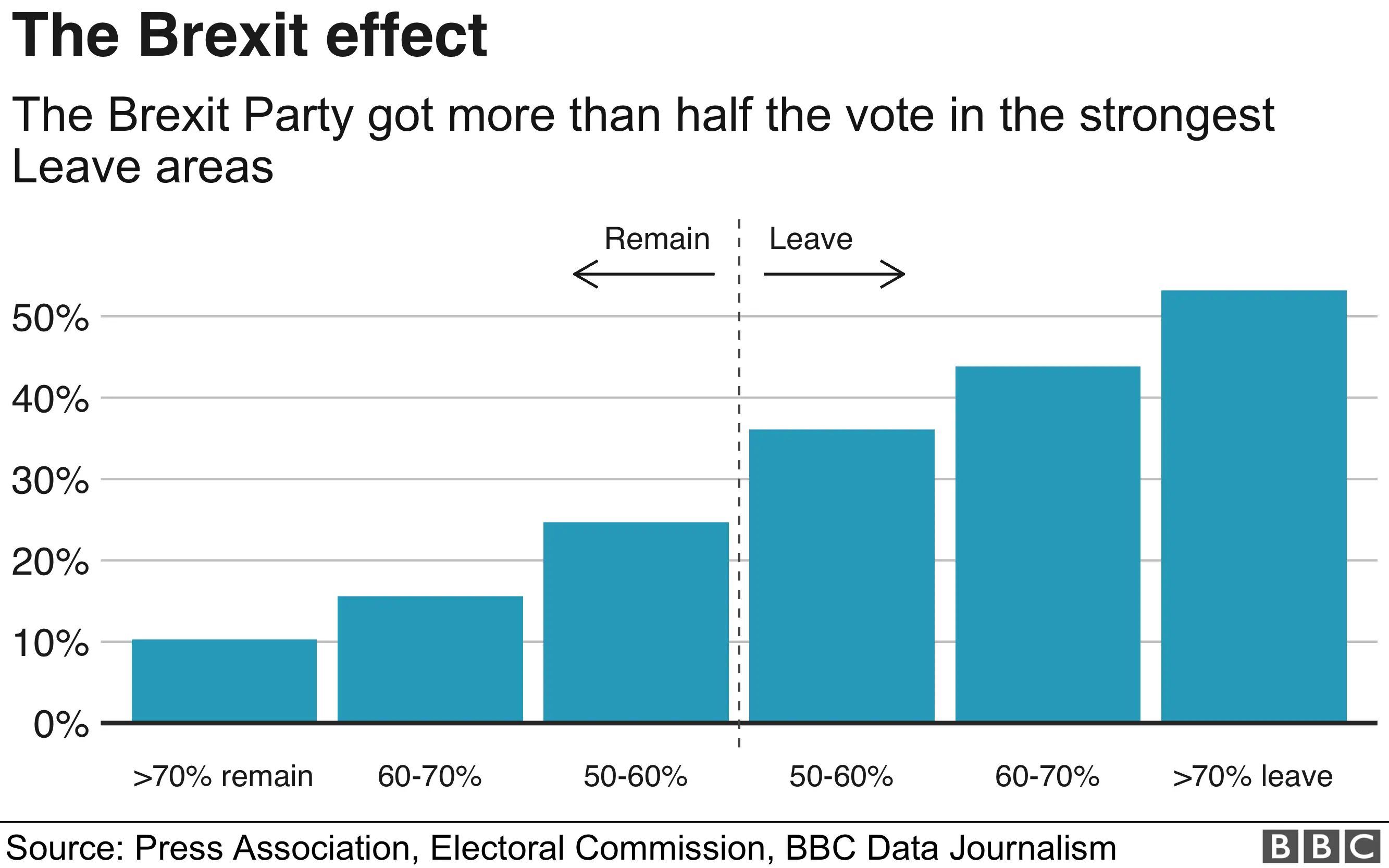

The Brexit Party performed much better in those areas that voted most heavily for Leave in the 2016 referendum than it did in those places that voted most heavily for Remain.

As a result, the party scored much less well in London (18%) and Scotland (15%) - where a majority voted for Remain - than in the rest of England (36%) and Wales (32%), which had provided the foundations of Leave's success in 2016.

A rebuff for the Tories

Because of this surge, the Conservatives fell to just 9% of the vote.

Governments often perform badly in European elections, as voters take the opportunity to express their disappointment with its performance without the risk that their vote might put the opposition into government.

Yet the rebuff suffered by the Conservatives was far worse than the previous worst snubbing to have been suffered by a government in a European election. That was the 15% to which Labour sunk in 2009, during the darkest days of Gordon Brown's premiership.

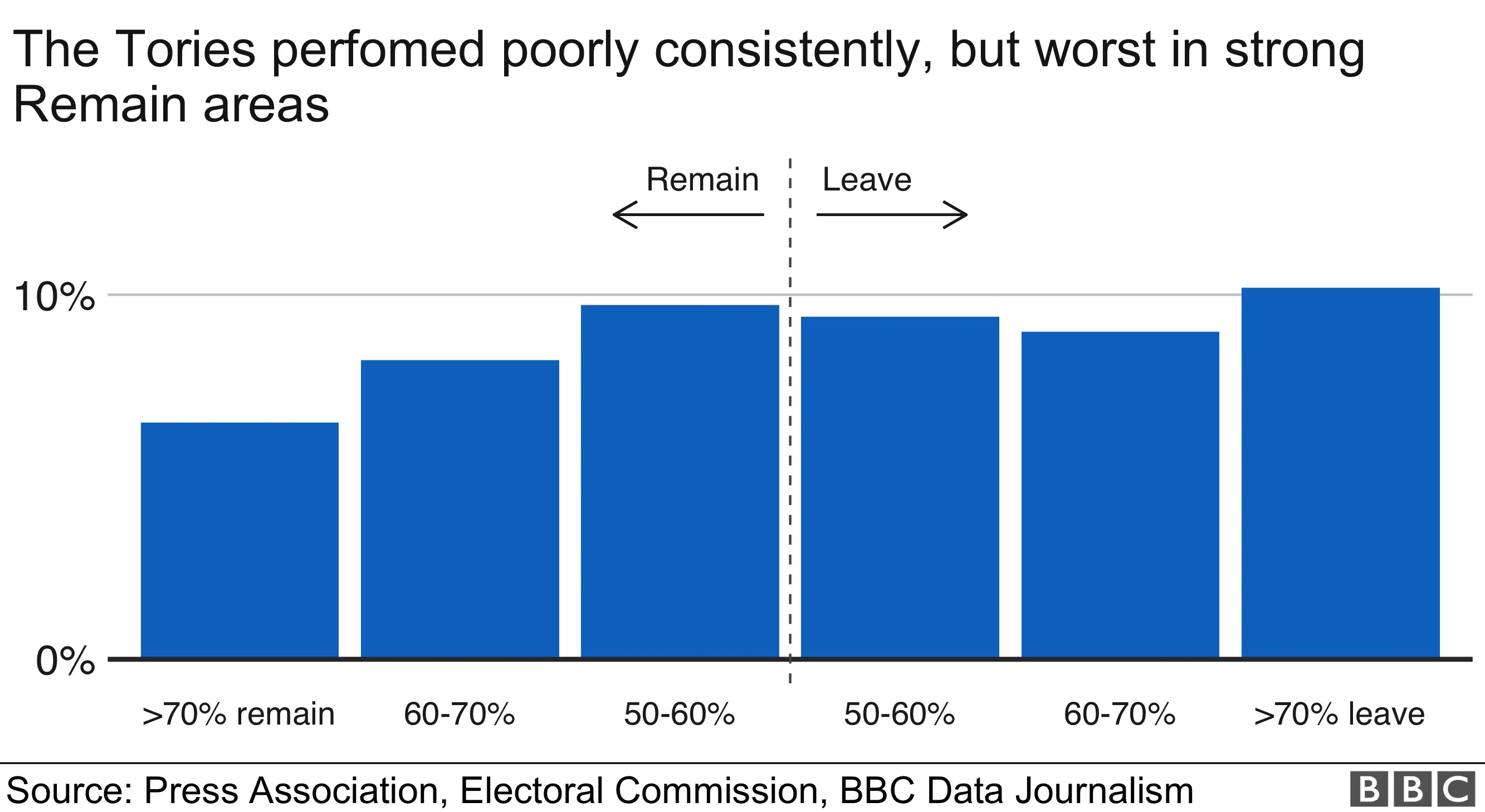

It was also easily the Conservatives' worst ever performance in a nationwide election. Its performance was weak everywhere - the party did not manage to come first in a single council area.

In sharp contrast to the position in the 2017 general election, when it was much stronger in Leave-voting areas than in Remain-inclined ones, the party did equally badly in both.

It is an outcome that would seem to confirm the message of the opinion polls that the party has lost the confidence of many Leave voters.

However, dramatic though it was, the outcome of the battle between the Conservatives and the Brexit Party had been widely forecast by the polls.

Indeed, politicians had already begun to react to it in the period between Thursday's vote and last night's count.

It arguably contributed to the downfall of Prime Minister Theresa May on Friday, while many of the candidates to be her successor are arguing that 31 October should be a firm and final deadline for the UK's exit from the EU.

The European election result will simply ensure that that debate continues.

The Lib Dems win Remain

The second contest in these elections was for the support of those who want to remain in the EU.

The polls had suggested that during the campaign Labour, which has been somewhat equivocal in its support for a second referendum, had been losing the backing of Remain supporters to the Liberal Democrats and the Greens.

However, there was disagreement as to whether the Lib Dems would challenge Labour for second place.

In the event, the Lib Dems won this battle hands down.

The party won 20% of the vote, its best European election performance ever, while Labour secured just 14%.

Sir Vince Cable's party not only beat Labour but managed to come a clear first in those places that voted most heavily for Remain including, most remarkably, in London.

There is no doubt that the party was the single most popular party among Remain supporters, a position that had hitherto been enjoyed by Labour.

The Lib Dems, who are themselves about to embark on a leadership contest, will hope the outcome signals that the party is finally recovering from the dramatic decline it suffered following its involvement in the 2010-15 coalition.

However, it was not the only party in favour of a second referendum to do well.

So too did the Greens, whose 12% of the vote was its best European election performance since 1989. However, in its case support was only marginally higher in Remain-voting areas.

In Scotland, the SNP, led by Nicola Sturgeon, won no less than 38% of the vote, its best ever European election result. It is an outcome that confirms its dominance of the electoral scene north of the border.

In Wales, Plaid Cymru also enjoyed some success with 20% of the vote, its highest since 1999.

Labour loses support

Though nothing like as devastating as the loss suffered by the Conservatives, Labour's poor performance could, in truth, also lead to a rethink just as important as that now going on inside the government.

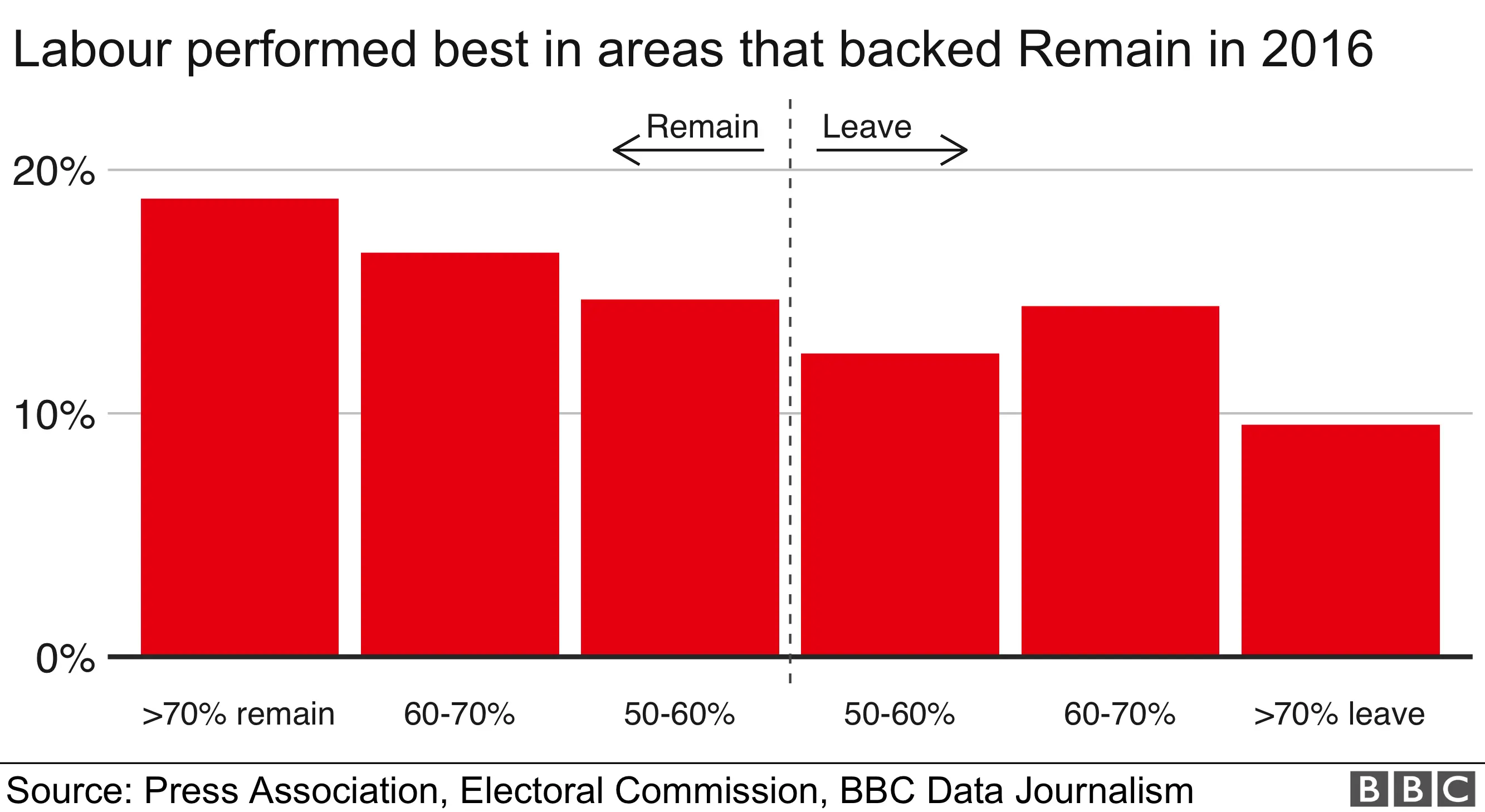

The party's attempt to keep both its Remain and its Leave supporters on board seems to have resulted in a loss of support among both groups.

Although Labour's vote fell most heavily in the strongest Remain voting areas, its vote also fell, by as much as 11 points, in the most pro-Leave areas.

There have already been signals from Labour that it might now fall in more firmly behind the idea of a "confirmatory vote" in which whatever deal is eventually struck with the EU is put before voters in a second referendum.

It will hope that this stance will help reverse the loss of support to the Lib Dems and Greens, without losing it too much ground among its minority of Leave supporters.

Such a development would certainly ensure that the government and the opposition are further apart on Brexit than at any point since the EU referendum.

On the other hand, the newest of the pro-second referendum parties, Change UK, led by Heidi Allen, had a bruising night, winning just 3% of the vote.

Even in London, where its hopes were highest, the party managed to win no more than 5% of the vote.

It seems likely that the party will have to seek some form of collaboration with the Lib Dems rather than continue to attempt to compete for much the same body of voters.

Inevitably, the outcome of the two battles led those on the Eurosceptic side of the Brexit argument to say the result showed that the electorate were willing to leave the EU without a deal.

Those in favour of a second referendum claimed the result indicated that voters wanted just that.

PA

PAIn practice, it would seem safer to argue that the outcome confirmed that the electorate is evenly divided as well as polarised between those two options.

Overall, 35% of voters voted for parties comfortable with no deal (the Brexit Party and UKIP).

Equally, 35% backed one of the three UK-wide parties (Lib Dems, Greens and Change UK) that supported a second referendum. If Plaid Cymru (1%) and the SNP (3.5%) are included, the Remain share of the vote is just over 40%, although the SNP is known to secure considerable support from those who voted Leave.

Far from providing a clear verdict, the result simply underlined how difficult it is likely to be to find any outcome to the Brexit process that satisfies a clear majority of voters.

Meanwhile, the poor performance of both the Conservatives and Labour will inevitably raise questions about the future of the country's two-party system. At 23% their joint tally was well below the previous all-time low of 43.5% in 2009.

European elections are, of course, not the same as a general election; voters have long shown a greater willingness to vote for smaller parties.

However, the issue that caused both parties such difficulties in this election - Brexit - is not going to go away any time soon.

In truth, both the Conservatives and Labour have been on notice that they need to handle the issue much better than they have done so far.

Otherwise, voters might yet turn elsewhere at the next general election too.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for an outside organisation.

Sir John Curtice is professor of politics at the University of Strathclyde. He worked with Stephen Fisher, associate professor of political sociology, University of Oxford; Patrick English, associate lecturer in data analysis, University of Exeter and Eilidh Macfarlane, a doctoral student at the University of Oxford.