Brexit: What deal did MPs reject?

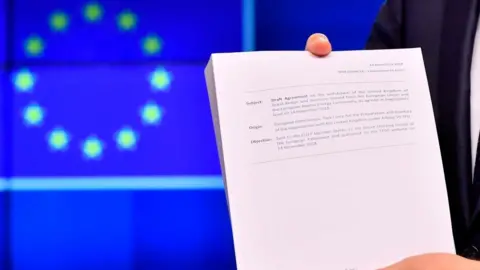

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMPs have rejected Theresa May's Brexit deal for a third time. The government lost by 344 votes to 286, a majority of 58.

But on this occasion there was a key difference: MPs only voted on the withdrawal agreement and not the political declaration. Previously, both of these were voted on and rejected.

So, what are they?

Withdrawal agreement

This is the deal the UK government negotiated with the European Union, over 18 months, and it sets out the terms of the UK's departure from the EU.

First published in November, it is almost 600 pages long and some of the key areas it covers are:

The transition

Under the withdrawal agreement, the UK would enter into a 21-month transition period with the EU after Brexit.

During this time the UK would continue to follow EU rules and remain in the single market and customs union to allow frictionless trade to continue. The UK would also lose membership of EU institutions.

The transition period could be extended, but only for a period of one or two years.

Money

This is known as "the divorce bill" - the amount of money the UK would need to pay the EU to settle its obligations.

Although no figure appears in the document, it is expected that the UK would pay at least £39bn over a number of years.

The Irish backstop

The most controversial part of the withdrawal agreement is the Irish backstop, which has proved to be the main reason it cannot command a majority in Parliament.

The backstop is the insurance policy designed to prevent a hard border in Ireland after Brexit. It would kick in at the end of the transition period in the event that a comprehensive trade deal, that avoids the needs for checks at the Irish border, is not reached between the UK and EU.

The terms of the backstop would effectively place the UK into a temporary customs union with the EU. Critics worry that the UK could find itself trapped in this arrangement for years, leaving it unable to pursue its own independent trade policy (signing trade deals with countries like the US).

Citizens' rights

During the transition period, UK citizens in the EU, and EU citizens in the UK, would retain their residency and welfare rights after Brexit.

The withdrawal agreement also allows citizens who take up residency in another EU country during the transition period (including the UK, of course) to be allowed to stay in that country after the transition.

Political declaration

The political declaration - also published in November - is all about the future relationship between the UK and the EU, after Brexit.

This document is far shorter (just 26 pages) and, unlike the withdrawal agreement, it is not legally binding.

Some of the keys areas it covers are:

Trade

The document calls on the trading relationship to be "as close as possible" and says there would be an "ambitious, wide-ranging and balanced" economic partnership. But it does not a set out what the final outcome for UK-EU trade will look like.

Customs

The political declaration refers to an "ambitious customs arrangement". The concern, from some, is that this could turn into a permanent arrangement that could prevent the UK from pursuing its own independent trade policy.

The government dismisses this concern, and argues that there is nothing wrong in wanting ambitious customs arrangements in the future.

Irish border

Technology and other alterative arrangements would be considered in order to keep the Irish border open with no physical infrastructure (eg border posts). However, presently, there is no border which the EU shares with a non-EU country that is entirely open and frictionless.

Freedom of movement

The UK, according to the document, would take back control of its borders and free movement of EU citizens to the UK (and UK citizens to the EU) would come to an end.

The document says both sides want to preserve visa-free travel for short-term visits (don't worry about your holidays) but it suggests by implication that visas could be introduced for longer stays.