Brexit: Are we running out of time?

MARK DUFFY

MARK DUFFYWith every day that passes, more politicians talk about the prospect of a "no-deal Brexit". This means the UK leaving the European Union without having reached an agreement on what happens next.

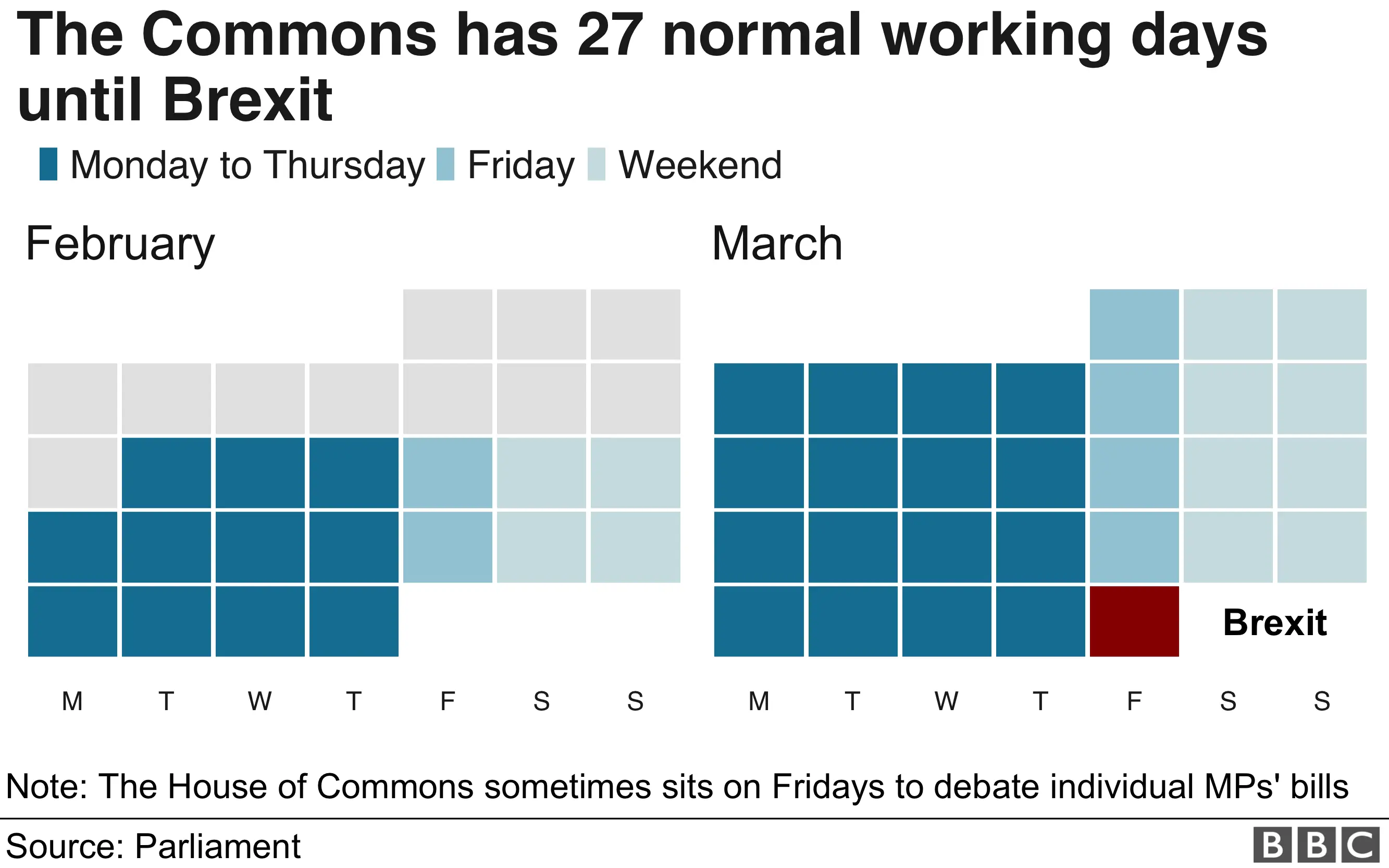

But when does it actually become too late for Theresa May?

What are the deadlines?

Only one deadline exists. According to current law, the UK will leave the EU at 23:00 on 29 March.

The date was set after MPs voted to invoke Article 50, the part of a European Union treaty that gives member states the option to leave the union. If a country invokes it, there are two years until it stops being a member. So when the prime minister delivered her Article 50 letter to the EU on 29 March 2017, the clock started ticking.

The 29 March date is also set out in a different law - The EU (Withdrawal) Act - which passed last year and brings all EU laws and rules back into the UK when it leaves the EU.

Can they change the date?

Yes. Despite the current exit day being set out in law, the Withdrawal Act gave ministers the power to change the date, provided this has the approval of MPs and Lords. It would also need unanimous approval from EU leaders.

EU figures have suggested they would agree to an extension of the Article 50 period if the UK decided to hold a fresh referendum or a general election. Experts at the UCL's Constitution Unit have argued that 24 weeks would be needed to hold a referendum.

It is less clear whether they would accept a UK request to postpone exit day to allow Theresa May more time to pass a deal. Some cabinet ministers have suggested the government could ask for a few extra weeks to get the legislation through, although the official government position is that it is committed to leaving on 29 March.

What needs to happen before the UK leaves?

This depends on whether the UK leaves with, or without, a deal.

OK, so what needs to happen if we are heading for 'no deal'?

If it looks as though a no-deal Brexit is likely, there are a number of laws that need to be passed to ensure continuity in crucial areas.

All of these pieces of primary legislation have been introduced by the government but are at different stages of the parliamentary process.

This involves, debate, approval, detailed scrutiny, amendments and final sign-off in both Houses of Parliament:

- The Trade Bill would need to pass to allow the UK to implement new trade deals. After a long hold-up, peers have completed committee stage, which scrutinises the bill line by line

- Another six bills designed to give ministers the power to take control of key areas of policy are yet to pass. These include agriculture, fisheries and immigration

- Other bills - such as the Customs Bill - have already been passed into law

On top of these pieces of primary legislation, Parliament will need to pass hundreds of statutory instruments.

What is a statutory instrument?

There are often changes in law that need to be made by the government but do not require a whole new piece of primary legislation, which would have to pass through scrutiny and debate in Parliament.

This is done through a statutory instrument, which is a type of secondary legislation.

Ministers are usually given the power to implement statutory instruments by previous primary legislation. Lots of the changes needed to prepare for Brexit are small and technical. The government can pass some of them without hassle but more contentious ones have to be approved by Parliament.

At the end of January, the Institute for Government think tank estimated 100 out of about 600 statutory instruments had been passed. Many of the others have been tabled but are yet to be passed. Commons leader Andrea Leadsom told the BBC on 12 February the government had laid 411, some of which are yet to be approved.

And if a deal is done, what has to happen?

The government has previously said it wants to pass all of the legislation mentioned above, regardless of whether we leave with a deal or not.

But if the UK is to leave the EU with a deal, there are arguably only two things Parliament has to do:

- First, MPs have to approve the deal - this is what they failed to do in January, when the government was defeated on the "meaningful vote" by a record 230 votes

- Second, Parliament has to pass a piece of legislation called the EU (Withdrawal Agreement) Bill, which implements the treaty. This could be a tricky hurdle for the government as it will give MPs and peers the opportunity to attach amendments to force the hand of government. And if MPs vote against the bill, the deal is off

How quickly can Parliament pass a bill into law?

It depends. The EU (Withdrawal) Bill, which set up the conversion of EU laws and rules to the UK on exit day, took almost a year to progress from introduction to being signed off by the Queen.

But Parliament can move very fast. For example, the 2017 Northern Ireland Budget Act passed through both Houses of Parliament in two days, with royal assent two days later.

When does the next 'meaningful vote' need to be?

There is no strict deadline between now and exit day for Theresa May to pass her withdrawal agreement and political deal.

The law states that there has to be a vote at some point, before 29 March, if the UK is to leave with a deal but it sets no date by which this has to happen.

The government has promised MPs another vote on Brexit by the end of February.

But if Mrs May has not managed to negotiate a new deal with the EU by then, it might just be another round of non-binding votes on different Brexit options.

The final vote would be delayed to the following month.

Is Theresa May 'running down the clock'?

The prime minister's critics say she is just pretending to try to get changes to the deal she signed with the EU so she can push the final vote on it right down to the wire.

Labour's shadow Brexit secretary Sir Keir Starmer says what she actually intends to do is return to Parliament after the 21-22 March European Council summit, the week before Brexit, and offer MPs a "binary choice" - her deal or no deal.

Holding such a vote a few days before Britain leaves the EU might scare enough Labour MPs worried about a no-deal Brexit into backing the prime minister to get it through.

The government insists this is not its strategy and it will hold a "meaningful vote" as soon as it gets the changes to the deal it is seeking from Brussels.

Does the EU have a say?

Before a deal with the EU can be ratified, the EU parliament has to approve it and EU ministers have to formally sign it off.

And what if we decide not to leave?

There is always the option to call the whole thing off by revoking Article 50. In December, the European Court of Justice ruled that the UK could reverse its decision to leave the EU without the permission of the other 27 member states.