Brexit: What will happen if MPs reject Theresa May's deal?

PA

PAIt feels like Westminster is tumbling towards a political crisis without modern precedent.

On Tuesday 11 December, the House of Commons will conclude five days of debate with a vote on a government motion to approve the EU withdrawal agreement and accompanying political declaration. The terms of the UK's departure from the EU.

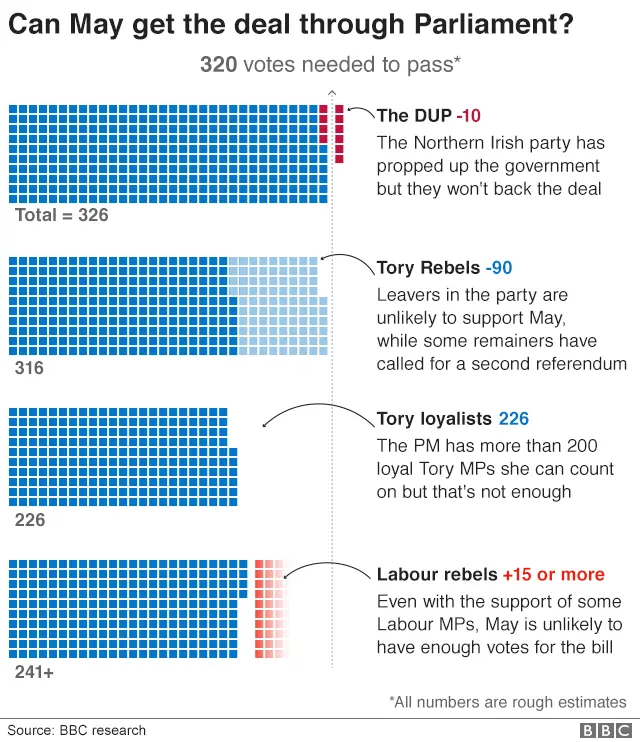

But at the moment, it looks as if Theresa May faces an incredibly hard job getting it passed.

She leads a government with a working majority of just 13. Only seven Tory rebels are needed to defeat it.

But according to the latest number-crunching by BBC researchers, 81 Tory MPs have said they object to the deal Mrs May hopes to sign off with EU leaders on Sunday.

With Labour, the Liberal Democrats, the SNP and even perhaps the DUP set to vote against the motion too, the withdrawal agreement looks set to be torpedoed in the Commons.

Between now and then Theresa May will exhaustively insist the deal is in the national interest and the only way of ensuring Brexit happens.

But if the withdrawal agreement is defeated, what happens then?

Leave without a deal

The default position in that scenario would be for the UK to leave without a deal.

Under both EU law and the UK's Withdrawal Act, Brexit day is chiselled into the diary for 11pm on 29 March, 2019.

That's when the EU Treaties will stop applying to the UK.

If Parliament rejects the deal, the same Withdrawal Act sets out what the government must do next.

Ministers would have up to 21 days to make a statement to the Commons on "how it proposes to proceed".

The government would then have a further seven days to move a motion in the Commons, allowing MPs to express their view on the government's course of action.

Crucially though, this would not be opportunity for MPs to throw a road-block in the way of a no-deal Brexit if that's what the government wanted to happen.

Whatever motion the government brings back to Parliament will now have to be amendable, after MPs backed a change to it tabled by Conservative MP Dominic Grieve.

MPs are hoping this will allow them to vote to rule-out a no-deal Brexit.

The government would find it hard to ignore such a vote - but it would not carry the legal force to stop the UK leaving without a deal next March.

Instead, the government would have to put new legislation before Parliament and secure the approval of MPs if it did not want the UK to leave without a deal.

As the clerk of the House of Commons, Sir David Natzler, told a committee of MPs last month, "there is no House procedure that can overcome statute. Statute is overturned by statute."

Have another go

PA

PABut in addition to the rigid legal position there would be the frenzied political reality.

The maximum three-week window between the government's deal being defeated and the requirement on ministers to propose a way forward would see several alternative scenarios come into play.

The prime minister could make a second attempt at getting the withdrawal deal through the Commons.

Sir David Natzler said, in procedural terms, that would be possible.

"The words might be the same but the underlying reality would be self-evidently be different", Sir David said.

Brussels might be persuaded to tweak the political declaration on the future relationship to meet the concerns of MPs.

Switch to 'Plan B'

Theresa May could try to return to Brussels to renegotiate the Northern Irish "backstop" - the main sticking point for many MPs. The government has long insisted this is not an option, because the EU has said the existing deal is final and there is no alternative.

Might Brussels give Mrs May some leeway if she loses the vote by a narrowish margin?

Some MPs hope she could get behind another version of Brexit at this point. There is support on the Tory benches for a membership of the European Free Trade Area, which would see the UK staying closely linked to the EU, like Norway.

This would not be a straightforward move - and would require extensive renegotiation, even if the EU was prepared to contemplate it, and the extension of Article 50, delaying Brexit day.

Then there is Labour's proposal for a permanent customs union - Mrs May has always ruled that out, but if enough MPs get behind it, it might be an option, although, again, it would need Article 50 to be extended to allow for more talks.

Theresa May resigns

Unlikely, given her track record of doggedly ploughing on against the odds - but if she is defeated by a heavy margin on 11 December she may feel she has no other option. There would then be a Tory leadership contest, which would turn into a fight to the death between the Leave and Remain wings of the party, with profound effects on the future of Brexit and, indeed, the country.

Theresa May is ousted by her own MPs

Jacob Rees-Mogg's band of Brexiteers famously failed to reach the magic 48 letters of no confidence in the PM to trigger a leadership contest last month.

But if she tries to cling on after a significant defeat on 11 December, more MPs could add their names to the list, forcing a no-confidence vote that she might struggle to win.

Another referendum

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMPs might suddenly shift in large numbers towards the idea of another referendum to break the Parliamentary impasse and open the possibility of stopping Brexit.

At the moment, about eight Tory and 44 Labour MPs have publicly committed to another referendum.

Theresa May is dead set against another referendum and it's hard to see an alternative Tory leader picking up that baton.

But the Labour leadership has said all options should remain on the table (including another referendum) and the SNP and Lib Dems say there should be one too.

However, a second referendum can only happen if the government brings forward legislation to hold one and a majority in the Commons supports it. There would have to be legislation. The rules for referendums are set out by the Political Parties, Elections & Referendums Act 2000.

The Electoral Commission's recommendation is that there should be six months between the legislation being passed and referendum day.

This could be shortened but, realistically, not by all that much. The UCL Constitution Unit, a research centre on constitutional change, suggests that could be 22 weeks.

So for the referendum to happen there would have to be a delay to Brexit - and that would require all 27 EU member states and the UK to agree.

A general election

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis is Labour's preferred outcome to the deal being rejected.

But as Dr Jack Simson Caird from the Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law says, "with the ticking clock of Article 50 it's very difficult to see that this represents a solution to the problem" of a deadlocked parliament.

That will be the other critical factor at play.

Unless the government asks for an extension to the negotiating period - ie Brexit being delayed - the time for parliament and the government to agree a way forward is incredibly tight. The clock won't wait.

There are two routes to a general election through the Fixed Term Parliament Act.

Two-thirds of MPs could vote for one. This is the quickest route - a poll could be held as soon as 25 working days later.

Alternatively MPs could go for a no confidence motion in the government - Labour has said they will table such a motion if Mrs May loses on 11 December.

This is a straight majority rather than requiring two thirds of MPs to vote for it.

This gives two weeks for someone to demonstrate they can command a majority in the Commons. If that does not happen, the 25 working days countdown to a general election kicks in.

Any election now would be on the existing constituency boundaries. The new ones have to be approved by the Commons and the Lords. And that has been put on hold until after Brexit.

'Negotiated no deal'

Another idea that has been floated is a "negotiated no deal" in the which the UK would ask the EU for a (paid) one year extension of membership before leaving on World Trade Organisation terms.

Some Brexiteers might like the idea but it's hard to see Parliament supporting such a move - with or without an explicit vote.

Because Parliament will have to come to a view.

As Maddy Thimont Jack, from the Institute for Government think tank says: "We do have Parliamentary sovereignty and there are clear ways for Parliament to express a very strong political view.

"I cannot see how a government can get through a legislative programme, for no deal, for example, if you don't have the support of Parliament."

Theresa May might have neutralised the chance of defeat in the Commons if she had found a Parliamentary consensus for the Brexit she planned to negotiate right at the start of the process.

Instead, she faces a fraught few days and a vote that will define the country's future for many years.

Right now, it looks like the government's deal cannot get through the Commons.

But the mood in Westminster could shift quickly in the current pandemonium.