What do the government's Brexit "no-deal" papers reveal?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBrexit Secretary Dominic Raab has set out what he called "practical and proportionate" advice in case the UK leaves the EU with "no deal".

Ministers say a deal is the most likely outcome but the government has published 25 documents of guidance for people and businesses across a variety of areas to try to avoid the "short-term disruption" which it admits is possible if the two sides cannot reach a deal.

BBC correspondents have unpicked some of the key details of the newly-published papers.

Economy: Kamal Ahmed, economics editor

The details on "no deal" published by the government are sobering. Just take one - trade across the border between the UK and the EU post-Brexit if there is no agreement.

If there is no deal and Britain reverts to "third country" status, the government has provided a long list of preparations that firms which export and import to and from the EU will be required to undertake.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCustoms declarations would be needed, tariffs (import and export taxes) "may also become due" and the government also says firms are likely to need to invest in new computer systems to track goods.

"If the UK left the EU on 29 March 2019 without a deal, there would be immediate changes to the procedures that apply to businesses trading with the EU. It would mean that the free circulation of goods between the UK and EU would cease," the government says.

That is the crux of the problem. Leaving the single market and the customs union without a deal means significantly higher barriers to trade with the EU.

And higher costs for firms that are engaged in that trade.

Some of the overall costs to the economy might be mitigated over the medium term by increased trading opportunities with nations outside the EU.

And the government has signalled that in some areas - such as the need for upfront payments of VAT on imports - it is doing its best to smooth the impact on cash flow by allowing for delayed payment systems.

That has been welcomed by business groups. But what is key from the documents published on Thursday is pretty straightforward.

The costs of "no deal" are likely to be substantial. And consumers and businesses would be the ones paying the bill.

Money: Kevin Peachey, personal finance reporter

Not so long ago, anyone going online to buy a flight, clothes, or even just a new spade could have been hit with a surcharge simply for the luxury of paying by credit card, debit card, or using a digital service such as PayPal.

The government described them as "rip-off fees" and in January they were made illegal as the UK adopted EU rules. In a "no-deal" scenario the government says those surcharges could return for anyone in the UK buying something from a retailer in the EU - something that happens regularly through online shopping.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEqually, any transaction across the border could become slower as UK financial services could no longer plug into the EU's payments system.

Those UK expats living and drawing a pension in Europe may also be affected. As the Association of British Insurers (ABI) has warned, there is a risk that, without an agreement, a UK insurance company paying - say - an annuity to a UK expat in the EU would no longer be authorised to do so.

That pension provider would either have to risk a fine by carrying on making these payments, would have to set up a subsidiary in the EU to do so, or could do a deal with a European counterpart.

The ABI argues that a relatively simple co-operation between UK and EU regulators could solve this issue, and allow people to continue drawing pensions and receiving insurance payouts.

The UK government said it would give temporary permission for financial firms in the European Economic Area to pay people in the UK.

Health, Hugh Pym, health editor

The concern in some parts of the NHS and the pharmaceutical industry is what might happen in a "no-deal" scenario if supply lines for medicines are disrupted.

If lorries get stuck at Calais and Dover because of customs delays, vital drugs like insulin needed in the NHS might be held up.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHealth and Social Care Secretary Matt Hancock has now written to NHS and social care organisations saying there is no need for hospitals, GPs and pharmacies to stockpile medicines or for doctors to write longer-dated prescriptions.

He says pharmaceutical companies should have six weeks' supplies built up to avoid any possible disruption.

To that end he has written to the companies asking them to clarify their plans for having these supplies.

NHS and industry leaders have welcomed the extra clarity provided by ministers with Thursday's documents.

They are pleased the government will allow drugs and devices tested elsewhere in the EU to be used in the UK. But they say stockpiling six weeks' worth of medicines will not be straightforward with only 200 days to go until Britain leaves the EU.

Farming: David Shukman, science editor

The big Brexit question for farmers is not answered in Thursday's documents: will there be frictionless trade for the £45bn in agricultural produce we exchange with the EU?

The National Farmers Union (NFU) has talked of an "Armageddon" in agriculture if there's no deal. "This is what's keeping us awake at night," one NFU official told me.

But one of the papers does give a taste of potential challenges to come. It covers organic food and highlights the need for a new process of certification.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen Britain leaves the EU, British organic food will have to be certified by UK bodies which will themselves have to be recognised by the EU.

That's a task that can take up to nine months, the document warns, and it may not be possible to start it until Britain actually becomes a "third country".

But without going through these hoops, Britain's organic farmers will not be able to export across the Channel.

The NFU describes this as a "cliff-edge" scenario. The Soil Association says delays could significantly hinder trade.

There's another concern as well: the EU currently runs a system for tracing organic produce and the UK will need to set up its own version. Many wonder if that will be ready by next April.

Science: David Shukman, science editor

One line in the technical note on research is ringing alarm bells. It spells out that when Britain is not a member of the EU, it will no longer be eligible for grants from the prestigious European Research Council (ERC).

While non-EU countries can take part in the much larger Horizon 2020 programme - and the government says it hopes that Britain will - the ERC, which is worth 17% of the total, will be closed to them.

This could matter hugely to dozens of researchers up and down the country. A lab at the Francis Crick Institute is exploring new vaccines against cancer and has just started to receive a five-year ERC grant of €2.5m. Would a "no-deal" Brexit mean that that flow of funding would stop at the end of March?

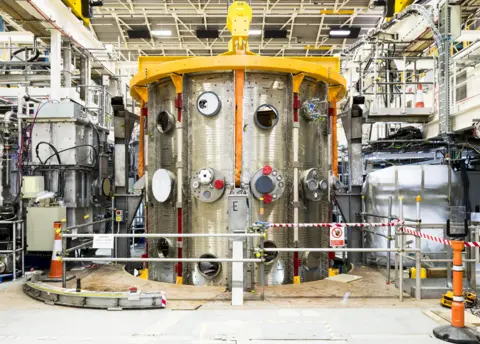

Science Photo Library

Science Photo LibraryAnother set of concerns is uncertainty over nuclear research as Britain leaves the Euratom treaty which covers radioactive materials.

Whether it's nuclear fuel or radioactive isotopes for medical use, arrangements will pass into UK hands.

Operators "may" need to apply for licences for trade with the EU, the government says. And the fate of Europe's fusion research centre at Culham in Oxfordshire is addressed but left unclear.

EU reaction: Damian Grammaticas, Europe correspondent

The EU has been publishing its own preparedness advice for months now, for all Brexit outcomes.

On Thursday, EU officials pointed out, as they have done many times before, that "the withdrawal of the UK is going to lead to disruption, regardless. So with a deal or without a deal. That's why everybody, and in particular economic operators, need to be prepared".

The impacts highlighted by the UK's notices for a "no-deal" scenario are, the EU side says, the "automatic, mechanical" effect of the UK quitting the EU and moving outside the single market and the customs union and all their associated rules and regulations.

In the event of a no deal, the impact will be felt on Brexit day in March next year.

EU sources say their efforts right now are going into negotiating a withdrawal treaty, as that is the way to mitigate a "no-deal" scenario. The EU's own notices say it will be bound, legally, to treat the UK as a "third country" after Brexit, and that will limit any ability to waive EU rules and regulations especially for the country.

Which puts the focus back on the issues still holding up the withdrawal treaty, such as the so-called "Irish backstop", if a "no deal" is to be avoided.