Brexit: Will a dividend help pay for increasing the NHS budget?

BBC

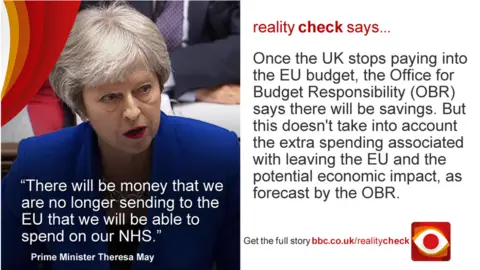

BBCThe claim: Extra funding for the NHS, up to 2023, will be part-funded by a Brexit dividend.

Reality Check verdict: Once the UK stops paying into the EU budget, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) says there will be savings. But this doesn't take into account the extra spending associated with leaving the EU and the potential economic impact, as forecast by the OBR.

The debate over how to fund the NHS dominated the main exchanges during Wednesday's Prime Minister's Questions, with the subject of the "Brexit dividend" being brought up.

The government says a combination of tax rises, economic growth and a "Brexit dividend" will help cover the costs of the increased spending in England's NHS budget.

Under the plans, the NHS annual budget will increase by £20.5bn by 2023.

On top of that, about £4bn will be given to the rest of the UK - although it will be up to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to decide how that is spent.

So is the UK government right to claim that we can expect a "dividend" by leaving the European Union?

Paying into the EU budget

When the government talks about a "dividend", it is referring to the annual contribution that we pay towards the European Union budget every year.

According to the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) - the independent body that scrutinises the public finances - the UK contributed just under £9bn net to the EU budget in 2016-17.

Under the government's current plans, the UK will remain a member of the EU until 29 March 2019 and it will continue to pay into the EU budget until then.

After that there is a proposed transition period in order to give more time to negotiate a post-Brexit relationship with the EU. The transition is scheduled to last until the end of December 2020.

The amount we pay during the transition period is expected to be similar to last year's net contribution.

So how much of a "dividend" will there be once we stop paying?

The OBR has set out what the potential savings might be.

It believes the UK will start saving money from 2020, £3bn initially and rising to £5.8bn a year in 2022-23.

That's based on how much we would have contributed to the EU budget, less the financial settlement or "divorce" bill.

But it's not as simple as that.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor one, while the OBR will have made some working assumptions about size of the "divorce" settlement, we still don't know what the final bill will be.

The latest UK estimate for the total is cost is between £35bn and £39bn. This is based on calculations the UK and EU have agreed, not the final amount on which the two sides have settled.

In April the National Audit Office said that the final bill remains uncertain and much of it depends on future events.

For some parts, like pensions, the UK would end up paying for decades.

But the government has already committed to pay for certain things associated with the cost of leaving the EU.

Last autumn the Chancellor Philip Hammond announced £3bn of funding over the next two years to help government departments prepare for Brexit.

Furthermore, a significant amount of the money the UK currently contributes to the EU ends up coming back to the UK to fund things like agricultural subsidies and science and research funding.

The government has said it will preserve the funding that farmers currently receive from the EU - at least until 2022.

In 2017, that was worth just over £3bn.

The UK also has to decide, among other things, if it will replace EU programmes that fund development in poor UK regions as well as research and development grants.

Economic uncertainty

On top of all this, there's also considerable uncertainty about how the economy will perform after Brexit.

According to the OBR, the saving we get from no longer paying into the EU budget will be outweighed if the economy underperforms.

It says that the impact of Brexit on the public finances will be largely determined by what happens to future tax revenues, which are linked to the strength of the economy.

And the OBR is already forecasting extra borrowing of about £15bn a year because the UK voted to leave the EU from 2018-19 to 2020-21.

It puts this down to things like lower immigration, lower productivity and higher inflation.

The government has been disputing whether the economy will take a hit. Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt told BBC Radio 4's Today programme on Monday: "A lot of the forecasts have been wrong and in fact the British economy has been... a lot more resilient than many people were forecasting."

But he did not dispute that the economy has been slowing.