The Houses of Parliament - a building catastrophe?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis autumn, MPs are due to debate whether they will have to leave the Houses of Parliament while it undergoes essential repairs. But could they be forced out of their iconic building by a potentially messy blockage?

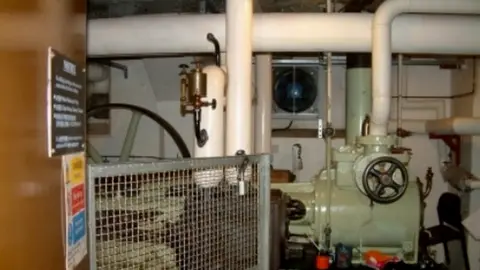

Turn on a gas alarm as a precaution, open a substantial iron gate and head down into a basement. The hum of machinery grows louder - and the smell grows stronger. Impressive but distinctly old-fashioned cylinders and pumps appear.

An engineer accompanying me explains that these are "sewage ejectors", dating from 1888.

An enterprising Victorian technology museum, you might be assuming, with working exhibits? But this is in fact the basement of the Palace of Westminster. And these Victorian antiques are all that stand between Parliament and an almighty stink.

The engineer is Andrew Piper, design director for Parliament's Restoration and Renewal programme, which is planning a project lasting several years and will cost billions of pounds.

CIBSE Heritage Group Collection

CIBSE Heritage Group CollectionHe explains that "everything from the toilets, the rainwater outlets - it all comes down to this point" - before being ejected out to the main London drain. The ejectors were installed to stop London's sewage invading the buildings after heavy rainfall.

And there they still are, working away, almost 130 years later. But, adds Mr Piper "we can't rely on these sorts of systems for much longer".

So what happens if they suddenly fail?

"If you can't use the toilets any more a building quickly becomes unusable. The end result would be potentially shutting the building down."

The sewage system is just one of several growing hazards. Mr Piper and his basement maintenance team struggle with constant fire dangers. There are modern electrical cables crammed next to older asbestos-covered steam pipes. And a system of vents that could carry smoke or flames swiftly through the building.

UK Parliament

UK Parliament The building that's meant to represent the British constitution is a kind of national monument to make do and mend, with lots of bits from different eras bolted on to each other and much left unwritten - like where all these cables and vents end up, and what they actually do.

The Palace of Westminster, one of the best known buildings in the world, is in a truly terrible state.

Some have known this for years. A joint committee, including MPs and peers, published a report last year which warned that the palace "faces an impending crisis which we cannot responsibly ignore".

"There is a substantial and growing risk of either a single, catastrophic event, such as a major fire, or a succession of incremental failures in essential systems."

Home from home

So how has this happened? And what does the state of Parliament say about the state of our politics?

Firstly, there's the belief that the building represents political stability. Maintenance has long been limited by MPs' insistence that nothing must stop them from sitting there. So any repairs have been crammed into recess times.

And there's another layer to this psychological attachment, says Dr Caroline Shenton, historian and former parliamentary archivist. The palace, with its bars and restaurants, gym and post offices, becomes a kind of home from home for MPs and peers, giving a "daily sense of continuity and security".

Add to that anxiety - in this increasingly angry, anti-politics era - about what public opinion and headline writers will say as the multi-billion cost of renewal emerges.

Sheffield University's Prof Matthew Flinders, chair of the Political Studies Association of the United Kingdom, who has closely followed the Restoration and Renewal programme, says this failure to take a decision is a classic example of what political scientists call "elite blockage".

The palace, he says, "casts a spell" on many who use it. It represents a kind of politics with "low expectations of public engagement" which "locks in by its design not only a two-party system but also a very masculine, adversarial kind of politics".

Those who benefit leave it to others to take tough unpopular decisions in the future. Meanwhile "the building can't take it any more - we've reached a crunch point."

uk parliament

uk parliamentHe would like the current problems to be seen as an opportunity - to open up the building and change the way we do politics. Public access could be greatly improved, especially for disabled people who currently struggle to enter.

Others say a renovated palace would prove a huge asset as Brexit Britain tries to reinforce its international reputation.

MPs are due to debate the latest restoration and renewal plan at some point this autumn. But those who have watched years of delay and disagreement don't expect swift action.

So will it take a catastrophe - like the 1834 fire which destroyed the palace's predecessor - to force a change?

"It's starting to look like that," says Dr Shenton. It might be that "the whole place just grinds to a halt".

"In terms of British pride," warns Prof Flinders, "if we wait for a catastrophe to close down Parliament, it's going to be an absolute disaster."

And as for the failure of those sewage ejectors - that would create an "elite blockage" like no other.

Chris Bowlby presents Parliament - A Building Catastrophe? on BBC Radio 4 on Monday 23 October 2017 at 20:30 BST. You will be able to listen via the Radio 4 programme website or download the programme podcast.