Stormont stalemate - how things stand

BBC

BBCIt's more than a month since the British and Irish governments began fresh efforts to restore devolution in Northern Ireland.

Breaking two and a half years of political deadlock between diametrically opposed parties is no easy task.

Add to that the out-workings of Brexit, a new prime minister - plus the findings of an inquiry into the financial scandal that collapsed Stormont in the first place - and restoring the place seems an insurmountable ask.

Talks are ongoing - but where are things at right now?

The latest round of Stormont talks was announced following the murder of journalist Lyra McKee by the New IRA.

The British and Irish governments had always planned to hold fresh negotiations - but the death of Ms McKee became a catalyst to do so.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOver the past six weeks, party leaders have been meeting at Stormont on a regular basis and five working groups were set up to deal with specific talks issues.

There is no set deadline.

At the end of May, the two governments agreed to "intensify" the negotiations - but at the moment it doesn't look like the parties are nearing an agreement.

What is being discussed?

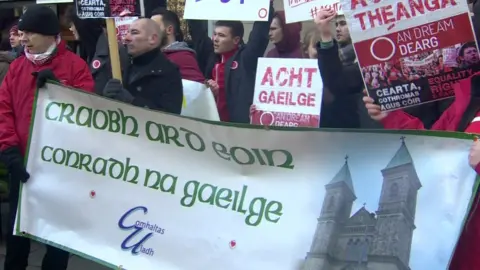

Without a doubt, the main sticking point is the call for an Irish language act.

It is being addressed through a working group on language and identity.

Sinn Féin has led the charge for that, previously saying it would not go back into government without a stand-alone Irish language act.

The DUP has been vehemently opposed to this, with party leader Arlene Foster saying the discussions could not lead to an outcome that was "five-nil to Sinn Féin".

Journalist Brian Rowan revealed on the Eamonn Mallie website that working documents from the talks are trying to focus on the content of future language legislation, rather than getting hung up on what any law should be called.

Other working groups are addressing issues such as reforming the petition of concern veto mechanism and improving the sustainability of the institutions.

How likely is a deal any time soon?

Although the Irish government recently said the mood music is much better than in previous rounds of talks, no-one is saying that an agreement is on the cards.

Reuters

ReutersTalks are due to continue on Monday - but one Stormont source told me they felt no-one was being serious enough yet, while another described the situation as "very fluid" and that this phase could reach a conclusion - not necessarily positive - by the middle of next week.

One theory is that the two governments could hit the pause button over the summer, and bring the parties back for a final phase of talks in the autumn.

BBC News NI understands that the Secretary of State Karen Bradley is planning to hold a reception next Tuesday to thank all those involved in the working groups for their efforts.

What could hold up a deal?

Some commentators find it hard to see how the parties could reach a deal by mid-July, before the publication of the report into the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) inquiry.

As it was the straw that broke the political back, causing Sinn Féin to collapse the institutions in January 2017.

It seems unlikely they would go back into government before waiting to hear its findings.

Charles McQuillan

Charles McQuillanThe British government is in flux right now too.

With a new prime minister coming down the tracks, there could also be a new Northern Ireland secretary.

Mrs Bradley is not openly endorsing any of the leadership contenders because of the talks process.

Reuters

ReutersThere is also the matter of renewing the DUP-Conservative confidence-and-supply pact, to ensure the government has a majority in the Commons.

After it was first signed in June 2017, other Stormont parties accused the British government of not being independent enough to oversee the talks.

There will be further confidence-and-supply negotiations when a new prime minister is installed, which could be another barrier to restoring devolution.

Reaching a deal is not totally impossible - but the same political obstacles remain.

No matter how much the mood might change, many feel breaking the parties' entrenched positions is the equivalent of a political Everest.