Operation Kenova: Your questions answered

Pacemaker

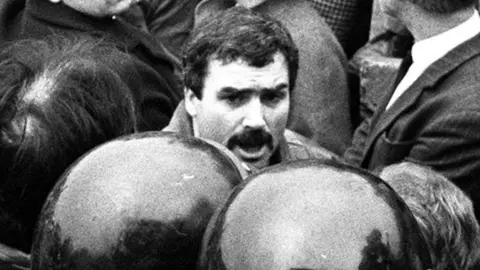

PacemakerFreddie Scappaticci lived a dangerous double life as a both a feared IRA executioner and an Army spy, reporting on the very organisation he killed for.

Given the Army codename 'Stakeknife', his unmasking as a British agent sent shockwaves through the republican movement.

On Friday, a major investigation into Stakeknife and the role of his Army handlers and MI5 was published.

BBC News NI explains the background to the double agent and the £40m investigation into his crimes.

Who was Stakeknife and what did he do?

Stakeknife was west Belfast man Freddie Scappaticci, though this has never been confirmed officially.

He was unmasked in the media in 2003 and although he denied the allegation, he moved into hiding in England where he died in 2023.

He joined the IRA in the 1970s and towards the end of that decade was recruited by the Army as an agent.

Throughout the 1980s he operated within the IRA's so-called internal security unit. Its primary purpose was to identify informers who were then kidnapped, tortured and shot dead.

Scappaticci himself was implicated in multiple killings while at the same time working as a spy, passing on intelligence about the IRA.

The IRA became suspicious of him around 1990 and stood him and his unit down.

What is Operation Kenova?

In 2016, the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) asked the then-chief constable of Bedfordshire, Jon Boutcher, to investigate more than 50 murders and any connection to Stakeknife.

The PSNI requested the external inquiry due to "its scale, size and complexity".

Called Operation Kenova, it had about 50 detectives from outside Northern Ireland.

To further underline its independence, no-one had a military or intelligence service background.

The Operation Kenova team was later tasked to examine other unrelated Troubles cases.

It has cost in the region of £40m.

Jon Boutcher, now the chief constable of the PSNI, released his report on Friday morning.

What is the purpose of the report?

Operation Kenova investigated the activities of Stakeknife, who was suspected of direct involvement in 18 murders.

The IRA unit that Scappaticci was part of was known as the "nutting squad" and its chief purpose was to identify informers.

Crucially, Mr Boutcher's team looked at the conduct of Stakeknife's handlers in the Army, as well as the security service, MI5.

It has been examining if the state was complicit in a catalogue of serious crimes.

The "nutting squad" dealt with the informers, including those falsely accused of being traitors, by shooting them in the back of the head after interrogations, which involved torture.

Bodies were usually dumped along rural border roads.

Who were the victims?

Operation Kenova is looking into more than 50 murders including that of Caroline Moreland, a Catholic mother of three who was abducted and murdered by the IRA in July 1994.

The body of the 34-year-old was found near Roslea, County Fermanagh.

Just before the ceasefires of 1994, she came under the suspicion of the IRA, was kidnapped, held for two weeks and shot dead.

After she was kidnapped, her interrogators made a recording of her in which she can be heard "confessing" to having been an informer.

PAcemaker

PAcemakerCaroline Moreland's daughter, Shauna, said she wanted to know why, if her mother was an informer, the state had not intervened to save her.

Shauna was ten when her mother was killed.

Speaking to the BBC's Good Morning Ulster programme, Shauna said her main goal was to "get someone to say that her life mattered".

"I didn't want prosecutions, I didn't care about that. I just wanted answers," she said.

"If she was informing then she would have had handlers who would have known she was missing and could have stepped in to save her."

- Read more victims stories here - The sound that signalled death for IRA 'informers'

Did the Army and MI5 co-operate with the investigation?

Yes. Much of the material relevant to the investigation is held by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) and MI5, as well as the Police Service of Northern Ireland.

Operation Kenova agreed information protocols with each organisation.

Mr Boutcher has stated getting access to all records was "challenging", involving lawyers and took time to obtain.

But as a result, he has said he has been able to search records "not previously given" to earlier investigations.

Operation Kenova has involved "12,000 investigative actions".

More than 300 people were interviewed, 40 of them under caution.

The first person it arrested for questioning was Mr Scappaticci in 2018.

As a result of an associated search, he was charged with, and admitted to, possessing extreme pornographic images.

Is anyone being prosecuted as a result?

No. Mr Scappaticci died in April 2023, before the Public Prosecution Service (PPS) had made decisions on files submitted by Kenova relating to 17 murders and 12 abductions, which occurred between 1979 and 1994.

Intelligence material made up much of the 60,000 pages of evidence it considered.

Last December, it said 15 other people would not face any action.

Following this, there were further decisions not to prosecute anyone, including people who are alleged to have been IRA members and retired soldiers involved in agent handling.

Pacemaker

PacemakerThe PPS said the evidence was "insufficient" to charge anyone.

In February, the Director of Public Prosecutions Stephen Herron said the value of Operation Kenova should not be measured solely in terms of prosecution outcomes, pointing to reports which are being prepared for families.

Has the report been censored?

No. Mr Boutcher put the finishing touches to the report in late 2022.

However, there was an eight-stage process to publication, with the final say resting with the PSNI, as it commissioned the investigation.

The stages included the government studying whether any of its contents compromised national security.

Last August, Mr Boutcher said the checks had not resulted in any redactions.

The report is an interim one, dealing with "high level themes and issues" concerning Stakeknife.

It will not contain a case-by-case examination of murders and incidents, nor identify victims at the request of their relatives.

Victims' families will receive individual reports at a future point in time.

There will also be a final report, likely to be published later this year, which will be more comprehensive.