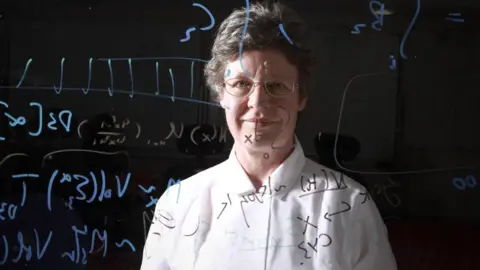

Northern Ireland scientist's role in black hole shock-waves find

Vanderbilt University

Vanderbilt University This week, scientists published evidence that supermassive black holes send shockwaves which distort space and time as they orbit each other.

One of the groups that made the discovery is the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves (NANOgrav) Collaboration, which is chaired by Northern Ireland native Dr Stephen Taylor.

The 35-year-old credits his love of all things space-related with seeing a partial solar eclipse during the summer of 1999, which also happened to coincide with the 30th anniversary of the first moon landing.

"The combination of those things and us learning about it at school - it just really sparked my imagination," Dr Taylor said.

He continued his education at Wallace High School in his home town of Lisburn and his passion for science, he says, never left him.

"I was always fascinated by it and that really played a big role in what subjects I chose for GCSE and A-level," he said.

EPTA/Stelios Thoukidides

EPTA/Stelios ThoukididesCrossing of paths

While studying for his A-level's, Dr Taylor went for work experience at a laser laboratory in Oxford.

It is there that he had a chance encounter with another Northern Ireland scientist whose work played a large role in his later research.

While at Oxford, he had the opportunity to attend a talk by Dame Jocelyn Bell-Burnell who discovered pulsars while a grad student at Cambridge.

Pulsars are dead stars which rotate and send out bursts of radio signals at extremely precise intervals.

"She gave a fantastic talk and I went up afterwards spouting the popular science I had read, thinking I knew everything," he said.

"But she was just really nice and kind of humoured me, if I am honest."

Pulsars would then be measured by Dr Taylor and his team in this latest paper.

"I think it's really nice that Northern Irish people are on both ends of this - because I certainly didn't hear accents like mine giving these kind of science interviews or talks," he said.

Dr Taylor then went on to do his undergraduate degree at Oxford, followed by a PhD at Cambridge looking at gravitational waves.

"At the time the idea was still theoretical. There were mainstream projects such as Ligo" - the US-based Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory - "but people were more focused on other aspects of physics.

"But my philosophy was, if I am going to do this I am going to enjoy it and this was what fascinated me most."

'Nasa-mad'

The first in his family to go to university, Dr Taylor said his parents always encouraged him to make choices that made him happy.

From there, the "Nasa-mad" Dr Taylor had the opportunity to work at the space agency's jet propulsion laboratory before spending some time at the California Institute of Technology.

This led him to begin taking up leadership roles, chairing a working group looking at gravitational waves and getting a permanent position at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee.

His team have been studying the signals which are emitted by pulsars and the affects of gravitational waves on their frequencies.

Dr Taylor described the radio beams from pulsars as being like light beams from a lighthouse. When the frequency at which they hit Earth changes, this shows gravitational waves as predicted by Einstein.

He said the most plausible cause of these waves is the orbit of supermassive black holes.

"We've seen loads of hints along the way but this is the first evidence in this kind of data set which is really exciting."

Dr Taylor said that, due to the frequencies, these black holes would be billions of times as massive as the sun and sit at the centres of galaxies.

"I never thought I would be involved in something like this. It was fun to be part of the physics and maths problems but I never thought it would get to this point," he said.

'No road blocks'

Dr Taylor said that the support of family, friends and his schools played a vital role.

"They never put up road blocks. I mean, if someone said they wanted to be a theoretical astrophysicist and try to make a big discovery, many would say, 'Catch yourself on'.

"But no-one ever really said that."

But it is not all plain sailing for people in Dr Taylor's field.

"It is not like in the movies, with a load of scientists around a computer saying, 'We got it; we're in'. There is no eureka moment.

"In this line of work it is a lot more about the small successes. The big breakthrough moments rarely happen and are often a long time coming."

Dr Taylor is looking forward to collaborating with similar projects around the world, combining their readings in order to learn more about these black holes and their gravitational affects.