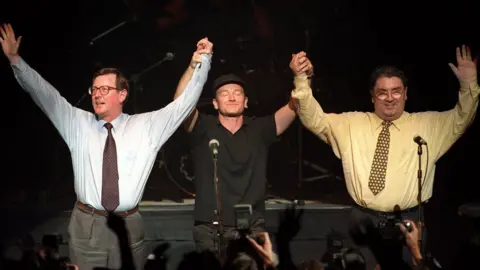

David Trimble: 'A politician who lived in present, not the past'

BBC News

BBC News Lord David Trimble never hid from the media, even in his most difficult moments.

At his last public appearance, a portrait unveiling at Queen's University, Belfast in June, he was short of breath and in some physical discomfort but he still spent almost an hour doing interviews.

It was the last time I spoke to him.

Back in 1995, I had lunch with him at the Europa Hotel in Belfast, along with another journalist, Vincent Kearney, now RTE's northern editor.

Jim Molyneaux had just announced his intention to stand down as Ulster Unionist leader and Trimble was considering entering the leadership contest.

Most commentators thought the job would go to John Taylor or Ken Maginnis.

Over lunch, Trimble said he had a dilemma.

"If I enter the contest, I'll win it," he said.

He was right. There were three rounds of voting and he won them all, even though his opponents were older and more experienced.

Trimble did not lack self confidence.

"I'm not too young, it's just that some chaps are too old," he insisted, with a smile, after becoming party leader.

In the 10 years that followed, he was seldom seen smiling. The signing of the Good Friday Agreement may have ended the worst of 30 years of violence, but for Trimble, it was the start of a whole new challenge.

'David the peacemaker'

To some within his own party, he was seen as Trimble the traitor.

On the world stage, he was David the peacemaker.

PACEMAKER

PACEMAKER Maybe that is why when he did interviews in places like Brussels, Washington and New York it was like seeing a different person.

He was visibly relaxed. Back home, he was looking over his shoulder all the time, and not just in a political sense.

Once he returned to Belfast, things often had deteriorated in his absence, and it meant another round of crisis meetings.

At that recent event at Queen's University, his wife, Daphne, told me she used to watch the evening news every night to try to estimate how late he would arrive home.

"You saw a lot more of him some weeks than me," she said.

It was an era before social media, and smart phones.

Trimble had a mobile phone, but hated being filmed using it. He was quirky like that.

Some people used other words like terse, tetchy and temperamental.

PACEMAKER

PACEMAKER He was also kind, considerate and a committed family man.

It was always hard to know exactly what mood he was going to be in. After all, this was someone who had a great love of opera, but was also a huge fan of Elvis.

His press officer in the late 1990s and early 2000s was David Kerr. They went everywhere together.

Kerr was fiercely protective of him.

Looking back at Trimble's career, he said in a recent speech: "I believe history will be kind to you, David. You aren't the first politician to be under-appreciated in your lifetime and you won't be the last."

There were a number of heated moments with the media over the years. So much so that at least one cartoonist depicted him with a permanent red face.

If Trimble did not like a question, he told the journalist, sometimes on air, sometimes off air, sometimes both.

That is not unusual for a politician.

What was out of the ordinary was that he kept giving interviews, the next day, and the day after, in spite of what had happened previously.

Lord Trimble was a politician who lived in the present, not the past.