The Irish artist who charmed East German children

Elizabeth Shaw estate

Elizabeth Shaw estateGenerations of German children have enjoyed the picture books written by the Irish author and illustrator Elizabeth Shaw but she's little known in the country of her birth.

From a childhood living above the Ulster Bank in Belfast's York Street, via the London Blitz to four decades spent as an artist in communist East Germany, hers is a remarkable 20th Century life story.

Shaw's autobiography Irish Berlin was published in 1990 in German, but has never been published in English.

Born in 1920, she had a clear recollection of York Street and of the riots that were common in the area:

"The rooms were large and dusty with high dirty windows, barred at the back of the house, some with stained glass, decorated in the style of the turn of the century.

"Opposite us towered the massive red-brick Gallaher's Tobacco factory.

"Life was regulated by Gallaher's Horn, the factory siren, which sounded in the morning, at midday and in the late afternoon. The air was pervaded with the odour of raw tobacco, stale beer and dust."

Elizabeth Shaw estate

Elizabeth Shaw estate"She always talked about her childhood, but she only went back twice, in the seventies and eighties," says her daughter, Anne Schneider.

"Hers was a family which was interested in having their children well-educated," she adds.

Shaw attended Belfast Royal Academy, a school she loved for its liberal atmosphere, but she also developed an early sense of social injustice as her autobiography shows:

"In the street we watched the 'dirty children' play. We were wistful and envious because we were not allowed to join them. They had bugs and diseases we were told. Sometimes they looked up at us, our noses flattened on the windowpane, and made rude faces."

Elizabeth Shaw estate

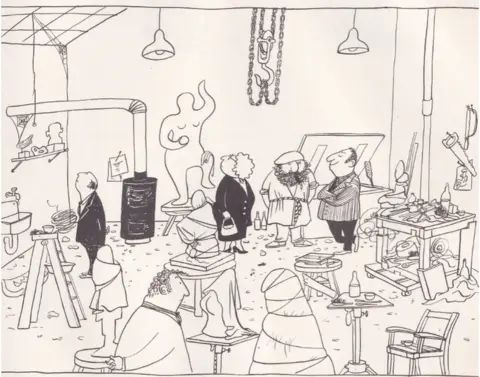

Elizabeth Shaw estateThe family moved to England when she was in her early 'teens and Shaw later studied at the Chelsea School of Art, where she became a convinced communist.

After war service as a telephonist and a sign painter, she married the Swiss sculptor, René Graetz, and in 1946 they moved to the bombed-out city of Berlin to help build a socialist Germany.

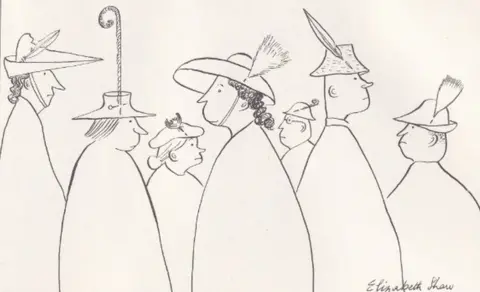

"In Germany she started working in caricatures or cartoons as she was used to doing this in England," says Anne Schneider.

In later years, she was worked as a cartoonist for the Communist Party newspaper, Neues Deutschland.

Elizabeth Shaw estate

Elizabeth Shaw estateIn 1961, the Berlin Wall was built and Shaw was there to view it at first hand.

"It had been long expected that something of the kind would happen because of the number of people leaving the country," she wrote.

"They would study in the east and then go to the west to get a job, where conditions were more amenable. It was clear that the GDR could not afford this strain on its resources...

"We went down to Wollank Strasse to see for ourselves and watched the wall go up, brick by brick, weeping grannies waving handkerchiefs on both sides, until the wall rose above them."

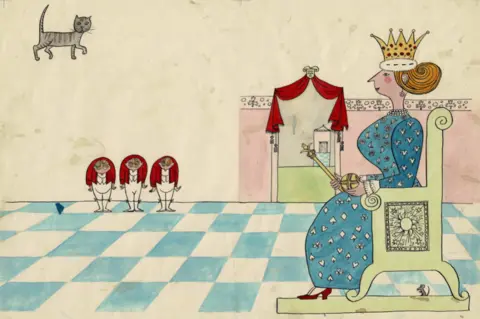

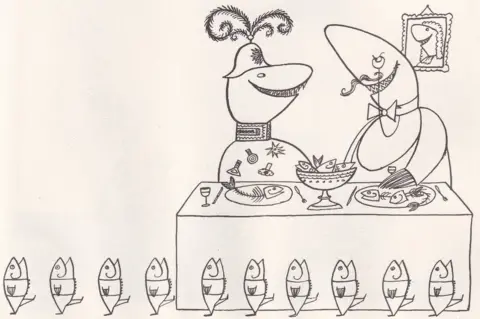

It was shortly after this that Shaw began her career as an author and illustrator of children's books.

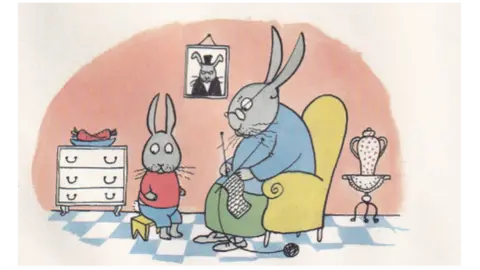

Books such as the Timid Little Rabbit and Bela Bellchaud and her Parrots became classics for East German pre-schoolers.

Elizabeth Shaw estate

Elizabeth Shaw estateDr Sabine Egger from Mary Immaculate College in Limerick has written about Shaw's work.

She grew up near Cologne in West Germany but received gifts of books from her godmother, who lived in the East.

"One of the books was the Timid Little Rabbit. I liked it a lot as a young child the way it was drawn... It's a very universal children's story and was hugely popular in East Germany," she says.

Dr Egger says East German children's literature at the time tended to reflect the socialist message of "you as an individual supporting the greater good".

In the case of the Timid Little Rabbit, this meant the village community protecting itself against a fox.

The books are still published in Germany and Anne Schneider, who runs an archive of her mother's work, explains that adults who read the books have passed them on to their children and grandchildren.

"Twice a year we go to Berlin and have a book stall. There are people who are 50 or 60 who remember reading these books. In East Germany that is, not so much in the west."

Elizabeth Shaw estate

Elizabeth Shaw estateShe remembers her family was unlike those of her schoolfriends.

"I knew that my mother and father were different from other parents because they were foreigners and they were artists. They worked at night."

In the 1960s, Shaw began a long friendship with the Ulster poet, John Hewitt. He organised an exhibition of her work at an art gallery in Coventry where he was director and another in Belfast in the 1970s. The Belfast exhibition was curtailed after three days when a bomb exploded near the gallery.

Hewitt described her art as "good-natured, whimsical, shrewd in observation...

"Often in the public squares, the streets of her townscapes you will recognise the trim figure of the artist herself, sketching under a portico or strolling with her portfolio under her arm."

As a foreigner with a British passport, Shaw was able to visit her family in England but her trips to Ireland were, by turns, traumatic and inspirational.

In 1969, she briefly visited Belfast and Londonderry as a reporter for Neues Deutschland.

"I contacted the Civil Rights movement and was able to see a side of Belfast which I had never explored before," she wrote.

Elizabeth Shaw estate

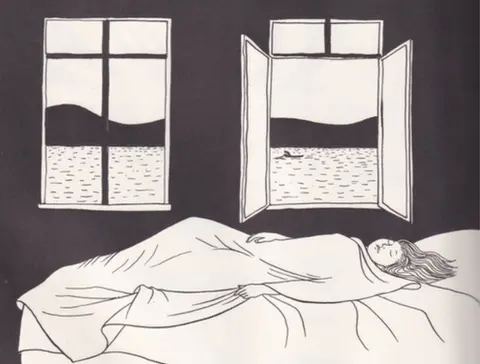

Elizabeth Shaw estateIt was on a trip to Rosses Point in County Sligo that she found a place of tranquillity.

"It was pleasant to walk barefoot, the clean wet mud squelching between my toes, and the best way to go in this moist land of no snakes. I crossed a stile into a field on top of the rise.

"Grey lichen-covered rocks showed through the grass in which grew pale blue harebells and the rare pure white flowers called Grass-of-Parnassus. Brown and white butterflies fluttered in the sun over clumps of yellow whin and purple heather."

Shaw's reminiscence of her trip to Rosses Point reflects what Dr Sabine Egger describes as: "things about the Irish mentality that she held on to and missed in Berlin."

Anne Schneider says her mother was pleased when the Berlin Wall came down:

"I think she liked the idea that her children and her grandchildren could see where her family came from."

Shaw's identity was complex. She evidently had a spiritual longing for Ireland but felt at one with her family and friends in England and had found her place in East Germany.

"My German, I regret to say, is still faulty. Nevertheless, I have become a Berliner," she wrote in her autobiography.

Elizabeth Shaw was granted her final wish after she died in 1992, when her ashes were spread in the Irish Sea.