NI 100: The truce that followed Belfast's Bloody Sunday

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

As the clock struck noon on Monday, 11 July 1921, a truce came into force which effectively ended the Irish War of Independence.

The conflict spanned two-and-a-half years and cost more than 2,000 lives.

The ceasefire was agreed three days earlier between the British government and Irish republican leaders - leaders who would soon form their own state on the southern side of the new border.

In Belfast, the final hours leading up to the truce were marred by bloodshed.

A total of 22 people lost their lives, including children, pensioners and many other innocent bystanders. A further 80 people were seriously injured and about 1,000 were left homeless.

The deaths came during an "intense and extremely violent bout of sectarian rioting which began at midnight on Sunday 10 July and did not abate until the afternoon of Monday 11 July," according to historian Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc.

In his book, Truce: Murder, Myth and the Last Days of the Irish War of Independence, Mr Ó Ruairc lists several reasons for the upsurge in violence, but the timing of the truce was a significant factor.

Pádraig Ó Ruairc

Pádraig Ó Ruairc

The truce coincided with the eve of the annual Twelfth commemorations - the height of the Protestant marching season.

Belfast frequently saw sectarian attacks rise at this time of year, but tensions were particularly high in the summer of 1921 as the new Irish border was not long in place.

'Betrayal'

Just three weeks earlier, unionists had celebrated the opening of Belfast's parliament by King George V - seen as the royal seal of approval for the newly-created Northern Ireland.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSo the idea that British forces had done a deal with the IRA caused anger and anxiety within unionism.

"This military ceasefire was arranged with a view to opening formal political discussions with the republican rebels," Mr Ó Ruairc explains.

"Loyalists would have been afraid that they were about to be betrayed - that if the British government was talking to the Sinn Féiners, they were going to be sold into an independent Irish republic."

Against this tense political backdrop, one incident sparked a cycle of violence which cost 22 lives.

Shortly before midnight on 9 July, an IRA gang opened fire on a Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) patrol in Raglan Street, west Belfast.

Constable Thomas Conlon was shot dead and two other RIC men were seriously wounded.

Pádraig Ó Ruairc

Pádraig Ó Ruairc

The ambush was followed by hours of tit-for-tat gun attacks between police, the IRA and snipers from both loyalist and nationalist areas.

The victims were from various age groups and backgrounds and most were posing no threat when they were targeted.

The dead included a 12-year-old Protestant, William Baxter, shot dead as he walked to Sunday school, and a 13-year-old Catholic Mary McGowan - a partially-sighted schoolgirl shot while crossing a road with her mother.

Several Catholic ex-soldiers were also among the victims, including elderly widower Bernard Monaghan who was shot dead on a doorstep in Abyssinia Street.

The former British serviceman was a father of 13, but had already lost his wife and at least eight of their children.

Monaghan family photo

Monaghan family photo"He was standing at the door looking out - as you do when there's something going on," his great-grandson Robert Monaghan told BBC News NI.

"Snipers were very common in those days, taking aim at people in the streets."

Mr Monaghan suspects a sectarian motive for the pensioner's killing, as gunmen knew "people living in certain areas were likely to be from a certain religion".

However, like many families who lived through this turbulent era, Bernard's loved ones were reluctant to discuss his death with younger relatives.

"I've a feeling that if I'd asked my parents about him, they would've told me to mind my own business," says Mr Monaghan.

But some eyewitnesses did speak about the events of that day, including Belfast IRA leader Roger McCorley.

"Sunday, 10 July was known in Belfast as Bloody Sunday," McCorley told the Irish Bureau of Military History.

"There was heavy fighting all over the city - even the city centre itself was swept by rifle and machine gun fire.

"Every weapon which we had in our possession was in action that day."

Central role

The bureau was set up by the Irish government in 1947 to record personal testimonies from ageing republicans who fought against British forces from 1913 to 1921.

McCorley's testimony outlines his own central role in Belfast's Bloody Sunday, as he led the gang which killed Constable Conlon in the Raglan Street ambush.

McCorley claimed the RIC patrol was in fact a "reprisal gang" and the IRA was defending Catholic residents from police attacks.

But according to Mr Ó Ruairc, the IRA operation was "an own goal" because Constable Conlon, a County Roscommon Catholic, was a republican sympathiser who previously warned the IRA of planned RIC raids.

"Often, the loyalist community would have been suspicious of southern Irish Catholics who were in the Royal Irish Constabulary and in the case of Constable Conlon it was justified," the historian says.

More than 80% of RIC members were Catholic in 1921 and many unionists distrusted the force.

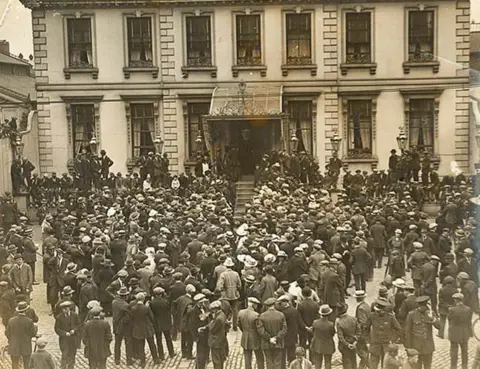

Walshe/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

Walshe/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

In contrast, the recently-formed Ulster Special Constabulary was comprised almost exclusively of men from Protestant and unionist backgrounds.

Many recruits were ex-members of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), an armed militia formed in 1913 to resist UK Home Rule legislation.

While unionists felt protected by the Ulster Special Constabulary, or "Specials" as they were nicknamed, nationalists felt threatened by the new police force, not without good reason.

The Specials earned a reputation for violent indiscipline - uniformed officers regularly attacked Catholic neighbourhoods in revenge for previous IRA attacks.

Reprisals by police were "justifiable and right in the eyes of God and man," according to the diary of Frederick Crawford, the Specials' South Belfast District Commandant in 1921.

Proni (INF/7/A/3/63)

Proni (INF/7/A/3/63)But reprisals only led to more attacks, and sporadic killings continued in Belfast long after the War of Independence truce took effect in rest of the island.

"One of the IRA leaders in Belfast said: 'It wasn't a truce we had in Belfast, but a pause'," says Mr Ó Ruairc.

"It was more of a theoretical truce in Belfast. It never took full effect and you still had occasional gun battles between the IRA and the British forces, which you didn't have in the south."

Although the truce calmed the city temporarily - only one of the 22 deaths happened after the noon ceasefire - the uneasy peace did not last long.

Snipers and rioters continued to claim lives on both sides, and while political negotiations were getting underway in London, the IRA set up new training camps in Northern Ireland.

Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

Topical Press Agency/Getty ImagesIn fact, the ceasefire boosted IRA recruitment, according to Thomas Fitzpatrick, an IRA commander in County Antrim in 1921.

"At the time of the truce, the strength of the Antrim brigade was roughly 140 or 150 active volunteers," Fitzpatrick told the Irish Bureau of Military History.

"Like every other brigade, the strength went up with a bound immediately the truce came. The truce was not observed by either side in the north."

But in 1922, the IRA's attention shifted south to the new Irish Free State, which was rapidly descending into a bitter civil war.

The truce paved the way to the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, which caused a split in the republican movement, with anti-treaty republicans arguing the deal cemented Irish partition.

According to the Irish Defence Forces, up to 4,000 people died in the Civil War, making it an even more deadly conflict than the one the treaty was designed to end.

The BBC News NI website has a dedicated section marking the centenary of Northern Ireland with special reports on the major figures of the partition era and the events that shaped modern Ireland.

You can also explore how Northern Ireland was created 100 years ago by listening to the Year '21 podcast series on BBC Sounds.

Above image of Frederick Crawford (INF/7/A/3/63) was reproduced with the kind permission of the Deputy Keeper of the Records, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland.