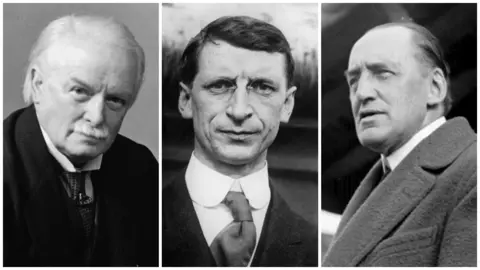

NI 100: Who were the major players in 1920?

BBC/Hulton Getty/PA Media

BBC/Hulton Getty/PA MediaThe partition of Ireland came after a series of seismic events - World War One, the Easter Rising, the War of Independence among them.

In the thick of these defining times were people who came to dominate the debate over Ireland's present - and to shape its future.

These are people who would become iconic figures - for better or worse - in the two entities that emerged from partition.

Here were the major players in Belfast, Dublin and London.

PA Media

PA MediaEdward Carson

The Dublin-born lawyer was the face and voice of unionism when the road to partition was being laid, but he had a complex relationship with the idea of a separate Northern Ireland.

Considered one of the most successful lawyers of his generation, Carson entered politics in 1892 and rose to prominence as one of Britain's most vocal opponents of home rule in Ireland, a stance made famous by his rousing and charismatic public speaking.

He was a key figure in the Ulster Covenant in 1912 - an oath of opposition to home rule - and the foundation of the Ulster Volunteers, a unionist militia designed to thwart attempts to establish an Irish parliament.

But, by 1914, with home rule looking increasingly likely, he supported a compromise position that would see Ulster temporarily excluded from the jurisdiction of an Irish parliament.

By the time the Government of Ireland Act passed in 1920, partitioning the island, Carson appeared to again see the option as the lesser of two evils. However, many historians believe that - as a southern-born unionist - the establishment of an Irish Free State hurt him and that he saw partition as a personal failure. In 1927 he was made Baron Carson of Duncairn.

Despite Carson's complicated relationship with partition, he remains an iconic figure in the creation of Northern Ireland, whose actions and legacy shaped the region for decades to come. His influence is still seen at Stormont, where Carson's statue overlooks Parliament Buildings.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesJames Craig

Considered the founding father of Northern Ireland, Craig was instrumental in its creation and became Northern Ireland's first prime minister after partition.

Born in Belfast, the son of a self-made millionaire whiskey distiller, Craig was first elected to Westminster in 1906 and forged a crucial role in Ulster unionism.

While Carson, who Craig invited to lead the Ulster Unionists, came to be the front man for unionism, it was Craig who took a key role behind the scenes. He was the architect behind the Ulster Covenant as well as the organisation of the Ulster Volunteers.

Unlike Carson, Craig appeared to embrace partition fully. He was instrumental in arguing for a six-county Northern Ireland, rather of a separation of the nine counties of Ulster, arguing that the six counties was the extent of the area unionists could hold.

He became NI's first prime minister in 1921 and held the role for 20 years. He was key in resisting efforts to altering NI's border post-partition, via the Boundary Commission. In 1927 he was made Viscount Craigavon.

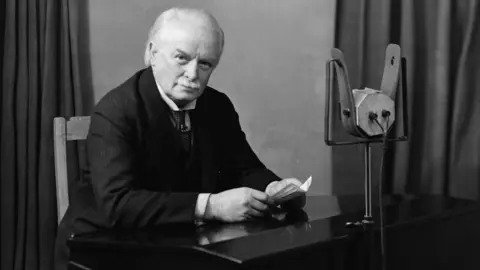

David Lloyd George

As the British prime minister from 1916 to 1922, Lloyd George not only had to deal with World War One but also the burning issue of how to solve the problems in Ireland.

The Easter Rising - and his government's hard-line response - had swung Irish popular opinion away from supporting home rule, which had already been approved at Westminster, towards independence. Meanwhile, unionists in the north, many of whom had fought on the WW1 front lines, waited to see how the government would repay their sacrifice.

Lloyd George initially sought to push through home rule, despite the war in Europe continuing to rage, as a possible solution. But waning support in Ireland - coupled with resistance to an attempt to extend conscription in Ireland - set Irish nationalists even further against it.

This was underlined in January 1919 when the dominant Sinn Féin set up the first Irish parliament and, coincidentally on the same day, IRA volunteers ambushed and killed two Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) officers, signalling the start of the War of Independence.

The battle between the IRA and British forces would continue until July 1921. In that time, following recommendations by a committee led by unionist Walter Long, Lloyd George created a new home rule bill, the Government of Ireland Act 1920, that would create two home rule parliaments - one in Dublin and one in Belfast, for the six counties of north-eastern Ulster.

Lloyd George's final act was in calling a truce with the IRA, paving the way to peace talks in London. The result was the Anglo-Irish Treaty, a document that ended British rule in the 26 counties of Ireland and solidified partition.

Independent News and Media/Getty Images

Independent News and Media/Getty ImagesJohn Redmond

The leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) from 1900 until his death in 1918, John Redmond was the foremost proponent of Irish home rule in the era.

Born in County Wexford, Redmond was first elected to Westminster in 1881. A loyal follower of Charles Stewart Parnell, the party's leader and father of the home rule movement, he succeeded Parnell in 1900 following his ousting over the public scandal of an extra-marital affair.

Redmond was on the cusp of achieving his goal when home rule was passed in Westminster in 1914, only to see it immediately postponed until after WW1.

A lifelong opponent of political violence, he encouraged Irish people to join the fight, believing it was Ireland's duty and also, in part, to display the country's loyalty so home rule would be implemented after the war ended.

However the Easter Rising in 1916 - and subsequent execution of its leaders - caused public opinion to swing away from home rule towards Irish independence and more militant republicanism.

In December of the year he died, the IPP was almost entirely wiped out in the Irish general election by a surging Sinn Féin. Ireland was set permanently on a path away from home rule - and towards partition.

Hulton Getty

Hulton GettyÉamon De Valera

The New York-born politician is probably the most influential Irish politician of the 20th Century - he was central to the formation of an Irish Free State and, as its leader, the evolution of it into an independent republic.

He first came to prominence in the Easter Rising, as a rebel forces commandant. He was captured and sentenced to death but was released following public backlash to the initial wave of executions and his American-birth at a time Britain was trying to convince the United States to enter World War One.

De Valera subsequently became one of the leading figures in the surging independence movement and, in 1917, was elected president of Sinn Féin. In 1919, after dominating the Irish general election, the party chose not to take its seats in Westminster, instead forming an Irish parliament (called Dáil Éireann), with De Valera serving as its president.

Following the War of Independence with Britain, De Valera tasked Michael Collins with negotiating the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. However, he opposed the deal - which copper-fastened partition in its establishment of a 26-county Irish Free State - and ended up the nominal leader of the anti-Treaty forces during the Irish Civil War between June 1922 and May 1923.

Later that decade, he returned to Irish politics - and would end up dominating it for decades to come, serving as Irish prime minister/taoiseach three times between 1932 and 1959 and then as president from 1959 to 1973. He died in 1975 at the age of 92.

British Pathé

British PathéMichael Collins

Like De Valera, Collins would first rise to prominence during the Easter Rising. Unlike De Valera, his career would be short - as commander-in-chief of the Irish National Forces, he was assassinated by anti-Treaty forces in 1922 during the Irish Civil War.

Collins was elected as an Irish MP in 1918 and served as a minister in the first Dáil Éireann - but he considered himself a soldier rather than a politician, and it was military leadership that brought him to renown.

He led the IRA during the War of Independence with Britain, directing the outnumbered rebels to conduct a guerrilla war against the British forces. The war lasted from January 1919 until a truce in July 1921, which then led to peace talks.

De Valera decided not to attend, instead instructing Collins to go. He, along with an Irish delegation, negotiated and agreed the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which provided dominion status for the Irish Free State, marking it as independent but still part of the commonwealth. The treaty also maintained - and confirmed - the partition of Ireland.

Collins appeared to know of the danger the treaty had placed him in, famously remarking that he "may have signed his death warrant".

The treaty proved to be highly divisive in Ireland, with De Valera and many others strongly opposing it. When the Irish parliament passed it, the stage was set for civil war and Collins' death in the months to come.